Adding the Sonderrechte southern states to the North German Confederation continued the unification of the Imperial German Empire. These southern states retained certain rights that the other Imperial German states did not have. These consisted of the kingdoms of Bavaria and Württemberg. In addition to those two kingdoms, another state that retained its rights was the Grand Duchy of Baden. Further, while the southern enclave of Hesse-Darmstadt was not in the North German Confederation, the northern enclave was and united with Imperial Germany under the auspices of the North German Confederation.

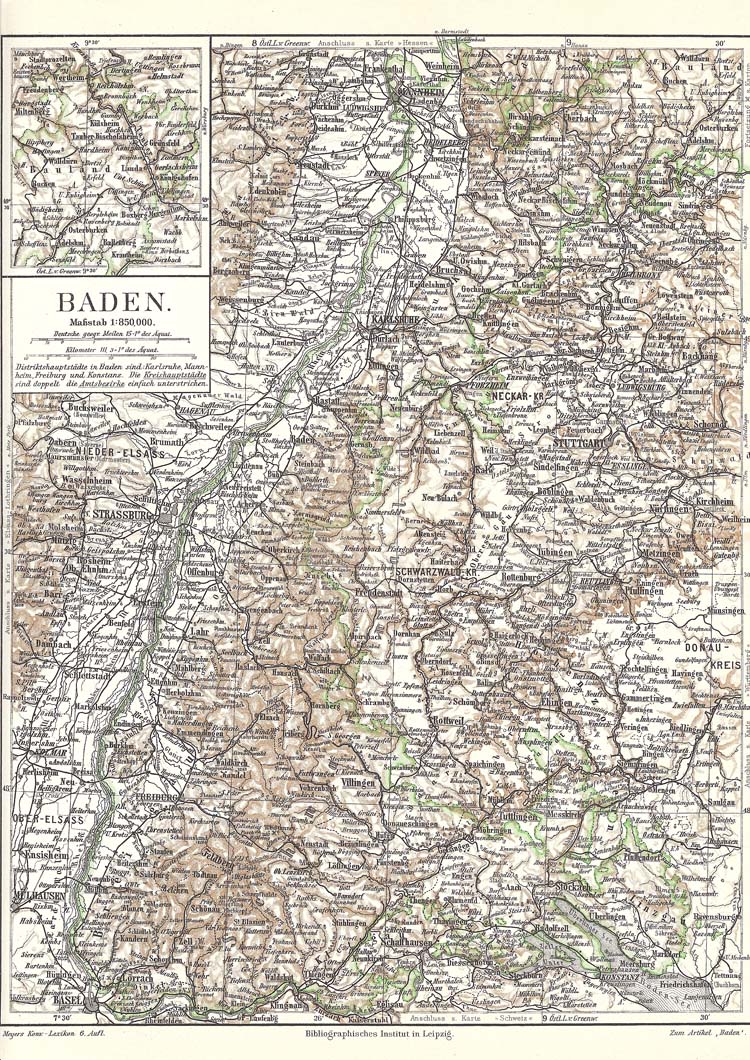

The Grand Duchy of Baden, a German state since the twelfth century, was a member state of the Germanic Confederation between 1815 and 1866. Baden quadrupled in size after 1815. Baden fought on the side of Austria during the 1866 war, and consequently paid Prussia an indemnity of 6 million guilders. Beginning in 1867, the Grand Duke placed a Prussian general in command of Baden’s troops and all Baden forces were trained according to the Prussian model. The military became a contingent of the Prussian army on 25 November 1870. Baden became a state of the German Empire in 1871 reserving certain separate privileges (Sonderrechte). The Grand Duke Frederick reserved the exclusive right to tax beer and spirits but Prussia controlled the army, the post-office, railways, and the conduct of foreign relations. The government of Baden was a hereditary constitutional monarchy with a parliament consisting of two chambers. The upper chamber was composed of all princes of the reigning family, certain members of the nobility, and eight members nominated by the Grand Duke. The lower chamber consisted of 73 popular representatives, the burgesses of certain towns elected 24, while the rural communities elected 49. Every male citizen of 25 years of age had a vote and balloting was secret. The elections were indirect, the citizens nominating the Wahlmänner and the Wahlmänner electing the representatives. The 1904 introduction of direct secret voting changed this system. This actually led to a left-leaning alliance of liberals and socialists that controlled the Catholics.

The internal politics of Baden centered on religion. The signing of a concordat with the Holy See, which placed education under the oversight of the clergy, led to a constitutional struggle, which the Protestants won. In 1867, a law was passed to compel all candidates for the priesthood to pass government examinations. The archbishop of Freiburg resisted, and on his death in April 1868, the See remained vacant. The Kulturkampf raged in Baden and lasted throughout the 1870s. Not until 1880 was there reconciliation with Rome. In 1882, the position of the Freiburg archbishopric was finally filled.

Consuls were maintained for trade with Bavaria, Belgian, the Netherlands, Austria-Hungary, Portugal, Russia, Norway, Spain, Württemberg, Argentina, Colombia, Greece, Mexico, Denmark, Ecuador, France, Great Britain, Honduras, Italy, Persia, Rumania, Switzerland, Turkey, Venezuela, USA, Paraguay, and Serbia. The capital city was Karlsruhe, the 38th largest city in the empire. The population was 1.8 million in 1914. Catholics outnumbered evangelicals by 2:1.

(Perris, 1912) pg. 290-302

(Kaiserliches Statistisches Amt, 1914)