This article started out as a hunt for information on German

imperial cadet helmets. As one thread lead to another,

I found that I had to learn more to figure out what I wanted.

It took a long time to have it all fall into place. The book

For King and Kaiser by Steven Clemente finally provided

the rest of the insights I needed in English. What I found

surprised me. Given a lifetime opinion of officer's,

general staffs and pre-commissioning training formed in the

US Army and by reading English language accounts of mostly

English officer ways, I soon found the Germans were quite

different. For each and every rule there were always exceptions.

We Value Loyalty and Obedience … exclusively.

It is outside of my scope to

go back to the historical foundation of the officers in Prussia but

it is important to know that it came from a feudal structure

with the service of vassals to the king. Nineteenth century

Prussians seemed to make out as though this was some sacred

bond when medieval reality was different as kings had difficulty

enforcing fealty. None the less this bond of vassal to king

and obedience to his will dominated the entire scene. We wanted

and insisted on loyal officers. Ones we could trust

through thick and thin no matter what to be loyal to the king.

Led by the nobility of the eastern provinces known as Junkers

, The admission to the officer ranks had to be tightly controlled

to enable only the loyal obedient types to enter into this

most respected and sacred profession.

Oh crud the population and army is expanding.

The

first kink in the armor was size. In 1914 the army was 761,000

men, 26,000 regular officers and 25,000 officers in the reserve.[i]

More officers were needed than the nobility could provide.

Historically there were nobles and officers from traditional

officer families. These were good solid stock that could

be counted on. Now expansion would find us accepting

others into the fold so the Junkers had to find a way to restrict

entry into the fold to only those who had the right attitude.

In general there were three classes of people.

- The

nobility and with them traditional old officer families.

- The

middle class. Some quite rich but families without the

benefit of nobility.

- The

lower class.

Class #1 had always filled officer ranks. Now, due to

the size of the Army, some of class #2 had to be let in and

under no condition what so ever would anyone from class #3

enter. Some is a relative word. By 1913, 70% of the army was

middle class and 48% of the generals were middle class.

Well, if the 1st class guys had to have some #2s

added in they certainly didn't need to hang out with them.

The tool to do this was the elite regiment. At first

all of the #1s went to cavalry regiments. However, not all

nobility could afford the extra expense of maintaining a horse

etc. so the Foot Guard regiments became exclusive too. The

bottom of the totem pole was the technical regiments of Pioneer

and Foot Artillery. Those fields that required thinking were

good for the #2s, the #1s would focus on saber waving. There

was a lack of prestige as well as technical schools required.

Technical schools meant having to pass courses as well as

taking time.

Even by the time of the death of Fredrick the Great 10%

of the army were #2s and they were all focused in Pioneer

and Foot Artillery regiments.

[iii] Regimental exclusiveness

did not end. By 1913, 16 regiments were exclusively

noble, Eighty % of cavalry officers, 48% of infantry

and 41% of field artillery were noble. A few middle classers

made it into the guards regiments. These were known as Concession

Joes (Konzessionschulzes) and were not very welcome.[iv]

An example from the 1912 Rangliste gives 36

of 36 non-nobles in IR154.

The

following table gives you a feel for branches in 1861.[v]

TABLE 1

|

Types of

Regiments |

Nobles % |

Non-Nobles % |

|

Infantry

Guards |

95 |

5 |

|

Infantry Line |

67 |

33 |

|

Cavalry Guards |

100 |

0 |

|

Cavalry Line |

95 |

5 |

|

Artillery

Guards |

67 |

33 |

|

Artillery Line |

16 |

84 |

|

Engineers |

16 |

84 |

*

For some reason I was never able to find reference

to Train Battalions. No telling where they fit but

as they were not saber guys probably quite low.

Did I forget that we wanted quality?

Short answer is that is wasn't that important. In fact it

could be a threat. As more #2s entered the officer ranks with

good solid skills those #1s who did not posses those skills

or scores had to be protected. The American army is rife with

nepotism but still the son has to have certain minimum skills.

Not so in the Prussian ranks. You had to have birth,

loyalty and obedience. Attitude could make up for many

other failings. In all schools there were exceptions made

to allow instructors to give extra credit to candidates with

good attitudes. So a non-passing score could be rescued

by deportment. Likewise a superb score of a #3 could be made

failing by his "attitude".

Schools were nothing like in the USA

The German school system provided the road into commissioning.

Just like the US system but it is REALLY different.

In today's US world

you go to primary, (8 years) secondary school, (4 years) and

then, when 18 years old, college (4 years). If that

college is an academy like West Point

, you are commissioned at graduation. You can join the Reserve

Officer’s Training Corps (ROTC) in a standard university and

be commissioned upon graduation after at least a couple years

of cadet training. All commissioned folks have 16 years of

school a college education and a commission as a second lieutenant

at about age 21 or 22. Source of commissioning matters not

after young lieutenants get into their units. Nepotism

(nobility) does.

Not so the Imperial German. The striking thing about

the German officer is youth. Far younger than any of

his western counterparts you could find officers at 17. Without

talking maturity or education you find yourself looking at

long service Germans rushing to get commissions and starting

the clock on seniority. You could go the cadet route or the

Fahnenjunker civilian route. Source of commission is very

important as is nobility.

If we look at the American system everyone goes to school

until age 18 and graduation from secondary school. Germans

started at age 6 and had to go to age 14. This was primary

school or Volksschule. Unlike western public schools Imperial

German secondary school was not free to the parents. It is

also VERY confusing because if the child was going to attend

secondary school he transferred into a private secondary school

at age 9. So parents had to start shouldering the economic

costs of the education from age 9 until they could stop supporting

the child. If the child would not be sent to secondary school

he would remain in primary school until age 14 all at no additional

cost to the parents.

So now you see why the emancipation of students became a major

concern of families. Perhaps you begin to ferret out why commissioning

and self sufficiency seemed so urgent. You also see that families

had to decide very early (age 9) to bear this expense or not.

Two basic types of Secondary Schools

While there were several types and focuses there were basically

2 types of secondary schools; "6 year" and "9

year". They were the same except for the addition

of 3 more classes in the 9 year version. At the end of 6 years

of secondary school you stood at the age of 14 the required

schooling age.

The

epitome of this education was to take an exam called the Abitur.

After 9 years of school. Passing this exam guaranteed you

good jobs. However you had to stay in secondary school until

age 17-18 and pass a very difficult test. You could also leave

school with a certificate of the highest grade qualified for.

About 30% of the 9 year secondary graduates earned the Abitur.[vi]

A test taken 3 years earlier was often far

more important to student and families. Known as the

One Year Certificate qualification, you could take it at the

end of 6 years and if passed you qualified to be a One Year

Volunteer (OYV). This meant only one year of service.

The cost however was huge almost 2000 marks or the equivalent

to a year in the university. Why would one do this?

The advantage of being able to seek a reserve commission was

worth going into debt to be a OYV.

[vii]

You

could also go to a cadet school. Cadets were an interesting

lot. By 1910 2/3rds of the cadets were non-noble.

[viii]The major investiture

was the quasi-formal clothing ceremony. The picture of the

Saxon Cadet I have should show how indifferent the issuers

were for size of these issues of the lower cadet schools.

Prussian lower schools did not wear helmets but each school

had a unique uniform. If it was too large you had no recourse

in this issue uniform but to grow into it.

[ix] Cadet life seemed to

revolve around efforts to find food as their normal fare was

inadequate. Some Saxon cadets moved into the Prussian system but

Bavaria

stood alone and

arguably always better. Saxony did maintain a separate cadet corps.

"The

Doctorate is the calling card but the Reserve Commission is

the open door."[x]

German society was made of haves and have less'. To be a have

you needed a commission. It didn't make you noble but allowed

you to do work in honor for a lifetime. A reserve commission

allowed you to be one of the elite of society. True,

not an active officer but a pretty good deal that lasted a

lifetime.

You could take the OYV examination at the end of the 6th year

of secondary school or after 6 years of the 9 year school.

You didn't have to finish the whole nine years. The

OYV certificate acted as a diploma of sorts for many employers.

An interesting point is that OYVs did not have to enter active

service for their year until they were 20. So the candidate

had years for education or employment.

An

additional certificate, the

Prima certificate was supposedly a requirement to take the

Fähnrich exam. Reality in officer selection allowed for

royal dispensation which ensured all the "right"

folks could take the exam. Or even not take the exam and have

an automatic pass. As a side, the Bavarian system was far

more rigid requiring an Abitur to get a commission. As a result

by 1914 only 15% of the Bavarian officer's had noble titles.

[xi]

The

number of dispensations is always played down. Not that

many is the conventional wisdom. Let's take a look at

test totals for a couple years:[xii]

TABLE 2

|

Year |

Civilians

taking Fähnrich test |

Cadets

taking Fähnrich test |

Total

taking Fähnrich test |

Officer test

taken after was school |

Selekta Cadets |

Total

Officers. |

|

1895 |

488 |

374 |

862 |

1179 |

82 |

1261 |

|

1900 |

344 |

351 |

695 |

970 |

88 |

1058 |

|

1907 |

315 |

337 |

652 |

925 |

63 |

988 |

Several hundred took the officer test without taking the Fähnrich

test. That is quite a few dispensations and exceptions by

my counting. In 1900 holders of the Abitur (and anyone

with a year in University) were exempted from the Fähnrich

exam[xiii].

If there were about 100 dispensations then about 200 Abitur

holders skipped the exam. Of the 25,670 aspirants between

1870 and 1914 who decided to leave school early and take the

Fähnrich test 43% of those were cadets[xiv].

Cadet

School aspirants

were far more desirable to a regiment than a civilian taking

the Fähnrich test. In 1871 the senior cadet school has

700 cadets and supplied 40% of the army"s officer requirement.

By 1889 the number of cadets had risen to 960 and the permanent

home at Gross-Lichterfelde was established. This was

the senior institution. Relate it to the civilian schools,

the top 3 grades from ages 14-17. There were no less

than eight junior campuses which fed the senior institution.

(Köslin,Postdam,Wahlstatt, Bensberg, Plön, Oranienstein,Naumberg,

and Karlsruhe .) You started at age 10 at the lower

school and moved to the senior school at about age 14. Families

paid for cadet school. It was not free or subsidized.

The number of officers provided annually during the 20th

century was 240.[xv]

The incentive again was to get these boys out to earn a wage

and not burdening the families with school costs. Scholarships

were available to help defray the cost and as a tool to ensure

unwanted folks could not afford it.

So What Were the Steps to Becoming an Officer?

As you can imagine the steps were full of exceptions and changes

all aimed at ensuring the right guy got in and the wrong guy

did not. The basic ten steps to commission were similar for

both the civilian method, Fähnenjuker, or the cadet schools.

Some of these had more exceptions than others.

Step 1. Find a Regiment

All

Guard and Cavalry regiments actively recruited nobles to keep

the regiments pure. Sort of like modern recruiting, all methods

were used to lure the young nobleman. They used fancy uniforms

and depot locations near fashionable large towns. Guard and

cavalry units could expect additional income of 1000 marks

per month for a candidate Remote lower regarded regiments

often had problems attracting new blood. None-the-less,

they insisted on a rigid class and social pick in step 2.[xvi]

The

maintenance of high social standards led to great shortages.

8% short in 1889 of total officer billets. In 1902 56 infantry

regiments received no applications! This was blamed on middle

class folks not wanting to wade through the army’s prejudice.

[xvii]

Step 2. Get Regimental Colonel to

sponsor you to qualify.

This was the key and maybe most

difficult step on the ladder. The family was looked

at in detail as well as the candidate. Sufficient

income was required and the regimental commander and

his other officers didn’t want to accept a fiscal

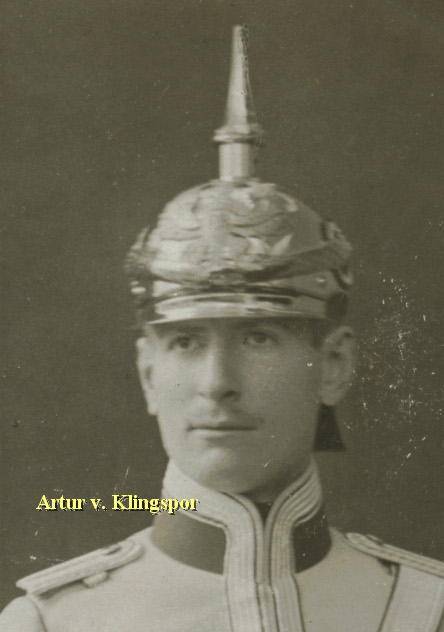

problem maker. A somewhat sad story is told by Vera

von Etzel about how Artur v.

Klingspor made it into the Kürassier-Regiment

von Seydlitz (Magdeburgisches) Nr.7. Very expensive

gear at that time and a burden even for his father,

Lieutenant Gen. Leo v.

Klingspor. The older brother was subsidized

by his father and received his commission. But he

was subsidized

after his younger brother, Hans Arvid, died

while in the academy. Perhaps the loss of a son

required his father to make sure his surviving son

was in the 'best'. But the enormous cost of a

'fancy' regiment would keep the regiments populated

by the more affluent - the 'vons'.[xviii]

The father and son went to a dinner to be seen by

all a one night precursor of step 8. The Colonel

would not give final approval until the Fähnrich

exam was passed or in the bag. Cramming with a tutor

for the exam was a standard practice.

|

|

Step

3. Pass the Fähnrich examination

Remember

you were supposed to have a Prima certificate or dispensation

to gain entry. 90% had a Prima Certificate. 75% passed the

first time. You could take it again and few if any failed

the second time. If indeed they did fail the second time it

was into the ranks as an OR. In 1890 the Kaiser demanded leniency

in grading. If leniency failed he used dispensations

which totaled over 1000 between 1901 and 1912.[xix]

At

the end of 6 cadet years or the age of 17 the cadets took

the Fähnrich exam and merged into the commissioning process.

Cadets were a little different because they were called Brevet

Fähnrich. If you really did well on the Fähnrich exam you

could be selected as a Selekta cadet and maintained at the

school. They became cadet non commissioned officers and "ran"

the non-senior cadets in the following year. There was a huge

advantage of being a Selekta. If you passed the Officers

exam you got commissioned. No need to be voted on buy

the officers of the regiment.[xx]

You could also stay at the academy, delay commissioning and

try for the Abitur. The Selekta helped you for the rest of

your military life. The Abitur was a civilian life advantage.[xxi]

Never the less the number of military Abitur holders grew

steadily from 1/3 in 1880 to 2/3rds in 1912. The number

of middle class officers who saw the lifelong civilian advantages

of the Abitur took sway.[xxii]

Step 4. Spend time in the ranks in the regiment

The

folks that passed moved into the regiment as an OR but was

referred to as an "avantageur". Officially, the

title was "Officeraspirant" that title was officially

changed in 1899 to "Fähnenjunker". He wore

a portapee that identified him. He lived in the barracks for

a period that varied by regiment from 6 weeks to 1 week. He

started as a Gemeiner and when he moved out became a Gefreiter.

All costs associated with his service were borne by him like

a OYV. At this point he could also have a civilian batman.[xxiii]

When

promoted to unteroffizer he got to eat at the officer's mess.

At this point he started being called Fähnrich. The word

Portapeefähnrich went away in 1899. A Fähnrichsvater

was appointed to be his mentor. Long drinking bouts and rules

of the mess were common place. While the Fähnrich was

encouraged to spend freely, indebtedness was a major embarrassment

for the entire mess. Step 4 passed quicker and quicker. At

first 6 months, the time shortened to three months (two if

you came from a cadet school) by the turn of the century.

[xxiv]

There were exceptions as some cadets left the academy with

some advanced training and were considered Patent Fähnrich.

They never were privates just Gefrieter.

The time in the ranks was so short folks didn't learn the

system. Only the reserve officers who went through the

year as a OYV understood the difficulties of the OR.

Step 5. Be promoted to Fähnrich "if

all went well".

The

aspirant applied to the colonel that he was "qualified"

and deserved a military qualification certificate (Dienstzeugnis).

If approved by the colonel and ALL of the officers of the

regiment he was officially promted to Fähnrich and paid a

salary. He also got to wear the silver sword

knot. Between 1892 and 1894 for example, of the cadets 59%

became Brevet Fähnrich, 10% Patent Fähnrich

and about 1/3 were Selekta.

[xxv]

Step 6. A course at the

Kriegschule.

Cadet

Abitur holders, Selekta cadets and civilian Abitur holders

who had been University students for a year were exempted

from this requirement. However, If you look at the ages you see that expanded civilian education

took time and money whereas you could skip the education and

go into the commissioning system and start making money and

seniority. This course shrunk in length as the need for officers

became more pressing and the desire became to commission in

1 year. At the end of the course you took the officer’s exam.

This course eventually went to seven months in length.[xxvi]

Step

7. Pass officer exam (become a DegenFähnrich) and return

to regiment.

Selekta

Cadets went straight to step 10 if they passed. . Passing

was not a problem (98% pass with re-take option.). Obedience

and attitude came before grades. It was considered far easier

than the Fähnrich exam.

[xxvii] At the regiment the

Fähnrich waited (briefly) for a vacancy and for the next steps

to be completed.

Step 8. Regimental officers balloted,

to see if they agree to accept candidate.

Selekta

cadets did not have to undergo this. Majority vetoes were

final. Minority vetoes had to be sent to the King for

decision. If you failed you were either sent to another regiment

for another try or to the reserves in disgrace or with a major

stigma. Few candidates failed as it required going against

the Colonel’s wishes. Some were rejected in full knowledge

because of a lack of personal wealth in which case the candidate

was sent to another regiment without stigma.

[xxviii]

Step 9. Colonel Recommends

Promotion to Second Lieutenant to Kaiser

The

Fähnrich became a second lieutenant and a member of the

social elite. EXCEPT if you were in the Foot Artillery or

Engineers. These two branches considered the newly commissioned

as supernumeraries until they had served one or two years,

attended technical school, and passed a qualifying exam.

[xxix] Technical schools

were viewed by the nobility as "schools for plumbers".

[xxx] Is there any question

why the nobles eschewed these branches?

Step 10.Promotion is Officially Gazetted[xxxi]

There were all sorts of rules for seniority and backdating

dates of rank but it is outside my scope to dwell on these.

Abitur holders finally got payback and got their dates of

rank predated 2 years.

Congratulations

you are an Officer or “Trick or Treat you are in the

Fleet”.

Being one of the

elite you found yourself in another world. There

were no rules for promotion. That’s right no rules.

Seniority and noble connections both mattered. A

normal progression was 8 years, to First Lieutenant,

14 to Captain, 25 for Major, and 30 for Lieutenant

Colonel. Pay was not reasonable as it was 1/5th

of his American counterpart.[xxxii]

Low pay with

high status meant that marriage had to be a business

deal where the girl brought the “bacon” to the

table. It was not unusual to use a marriage agency

nor for the brides father to assume the officer’s

existing debts. Marriage had to be approved by the

regimental commander to ensure the woman had enough

money and an unblemished record.

[xxxiii] Have you

ever noticed how unhappy German brides look in their

wedding pictures? Maybe it was cultural. At least

my wife smiled when we got married.

So life wasn’t

always rosy but now we know how you got to this

social plateau. Clemente’s book was heavily relied

on for citations in this article but as you can see

the pages and information had to be rearranged. What

are my conclusions?

-

Prussian Officers

were far younger and less well educated than

their western counterparts.

-

Wealth and social

position drove the train.

-

There were many

regiments where the have – less types resided.

-

For every rule

there were exceptions made for the right person.

So there it is in

short (well sort of not exactly 300 pages.). Have

at it all critiques very welcome.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[i] Clemente, Stephen, For King and Kaiser,

Greenwood Press, Westport , CT , 1992, p205.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Clemente, Stephen, For King and Kaiser,

Greenwood Press, Westport , CT , 1992, p3.

[iv] Ibid. pg 206.

[v] Ibid. pg 16

[vi] Ibid. pg 32

[vii] Ibid. pg 33

[viii] Op cit. Clemente, pg 111.

[ix] Ibid pg. 115

[x] Ibid. pg 115.

[xi] Ibid. pg 41

[xii] Ibid pg 258

[xiii] Ibid. g.43

[xiv] Ibid, pg. 212.

[xv] Op Cit Clemente, pg. 82-83

[xvi] Op Cit Clemente, pg 64

[xvii] Ibid. pg. 207.

[xviii] Wehrmacht-Awards thread, Prussian

Commissioning, 7/28/2004 Posted by Brian S.

http://www.wehrmacht-awards.com/forums/showthread.php?t=57874&page=2&highlight=commissioning

[xix] Op cit Clemente pg 43.

[xx] Ibid pg. 94

[xxi] Ibid. pg 101

[xxii] Ibid. pg 209.

[xxiii] Ibid. pg 72

[xxiv] Ibid pg 73-74.

[xxv] Ibid

[xxvi] Ibid, pg.150

[xxvii] Ibid, pg 150-157.

[xxviii] Ibid. pgs 158-159.

[xxix] Ibid. pg 160.

[xxx] Ibid. pg 210.

[xxxi] Martin, A.G., Mother Country Fatherland,

Macmillan & CO, London , 1936 pg 16

[xxxii] Ibid. pg. 161-162.

[xxxiii] Ibid. pg 163-164.