Military Service

Joseph P. Robinson

15 May 2008

Go to Page 2

Go to home

My initial article on the subject followed the somewhat simplistic view of universal military service as had been regurgitated in countless secondary sources. What I portray here is my view. It is different than the picture presented in any secondary source and I’m aware of. I’m sure there are mistakes and I will gladly take useful suggestions of improvement. Nonetheless this is done primarily for George and Pierre. Those two individuals have shared their knowledge aggressively and always given me intellectual challenges.

In order to understand the Army one must understand the macro picture of Imperial Germany. The population of Imperial Germany was inducted into the Army. i While this statement seems prima facie the way in which the population was inducted, the standards and rituals of service as well as the interests of those making the selection shaped the input of the Army. Before the war universal service was far from universal and there were several factors that seriously affected who got recruited. By the time you finish the first part of this article you’ll be asking what this has to do with universal military service – but it is all interrelated.

Class Structure

The population itself was split into thirds – not even thirds – but three different types. The aristocracy, the bourgeois, and the proletariat. Approximately two thirds of the population were what we consider the proletariat. 30% was the middle class or the bourgeois. That left about 1-2% for the aristocracy. This roughly approximates what has become famously known as the Prussian three-tier voting system. The three-tier system of voting was a huge right that the Aristocracy/Junkers wielded inside the kingdom of Prussia. Basically all voters who were males over the age of 25 were divided into three classes of voters based on the amount of tax revenue they provided. The richest 5%, were class one. The next richest 15% was class two. The 80 % left over were class three. Each class of order had an equal share of the vote for representatives to the Landtag or territorial parliament. So the top 5% had as much clout as the bottom 80%. Voter turnout in the lowest class was extremely weak, amounting to only 20% of the possible voters. Obviously, the aristocracy/Junkers were not real willing to give up this advantage as the Landtag was responsible for legislation covering commerce, tariffs, and banking. The three-tiered system of voting kept the aristocracy/Junkers and the rich in charge of the Kingdom of Prussia. Prussia dominated Germany and the Bundesrat.

Aristocracy

Aristocracy was supposed to provide any officer corps to the Army. The aristocracy could be depended upon. Education provided a springboard for the aristocracy to become officers but the expanding population outstripped the ability of the aristocracy to fill all the needs. Therefore, members of the bourgeois had to be allowed into the ranks of officers. Economically the aristocracy could have huge wealth all the way down to completely broke. The aristocracy tended to have assets and had a nasty habit of thinking that they did not have to repay debt—they were after all noble.

|

Nobility belonged to the Adelstand which was divided into Uradel, or "old" nobility, and Briefadel, or "patent nobility", (commoners elevated into the German nobility). Only a few German noble families could grant these patents. There were also some non-hereditary titles of nobility granted to members of certain orders. There were further subdivisions and a distinct pecking order. Hochadel vs. niederer Adel, or high nobility vs. lower nobility. Marriages were often considered unequal even though both persons were nobles because they were from different subdivisions. Not everyone with a “von” in their name was noble. For the most part, if you want to tell noble from non-noble based on the "von" the "von" in noble names is abbreviated "v.", while for non-nobles it is left as "von". |

Not all of the aristocracy was impoverished; they did generally through inheritance have huge assets. With a heritage as landowners in the eastern parts of Prussian many in the aristocracy became richer and richer after leveraging their estates. By 1911, the top 10% of the Prussian population owned 63% of the assets. Profit rates in industry were much higher than profit rates in agriculture. Investment in land was only extremely profitable around the margin of expanding cities. With investments in land and profits to the made in bourgeois industry, the aristocracy had to adapt. With huge investments in mortgages and costs for the land some 5000 estates went into bankruptcy between 1885 and 1900. Individuals who invested in industry did extremely well. There were almost 10,000 millionaires by 1911. 21,000 individuals from Prussia allegedly made an annual income of over 100,000 marks. ii To put this totally in focus however keep in mind that the aristocracy represented approximately 1% of the total population. The aristocracy was way overrepresented in the military. 70% of the officer cadets came from this 1% aristocracy. iii

The entire national identity was built upon nobility. Prussia originally was founded by nobility east of the Elba River. Collectively, these became known as Junkers.

Junkers is a well-worn word that few people truly understand. They were landed nobility. They were people who generated their income from the land, and the estates that they owned. They had many privileges to include a great deal of control over of the accession of officers into the military. They were given huge concessions in Prussia's three-tier voting system and a voice by the crown in granting tariffs and other protective acts to maximize the amount of income they could get from their estates. They were from rural areas and distrusted workers in the big cities. In exchange, the Junkers were supposed to give blind loyalty and fealty to the King of Prussia. The King of Prussia could depend on them through thick and thin. As the King of Prussia became the Kaiser under the KleinDeutschland unification, the power of the Junkers grew. In 1894, the agrarian league was founded, supported by these estate holders. Agricultural holdings as opposed to the mechanized wonders of the Industrial Revolution and socialism was where the Junkers were at.

Central to this power was an understanding in constitutional terms of where the army was. The Kaiser, the Junkers, and the military all considered that there was a direct tie between the Kaiser and the army. Civilian authority was of only limited use when dealing with the army. There was a constitutional question as to who called the shots in the army; the king who commanded it or the Reichstag that funded it. This question never came to a head, but it is the central point in understanding much of what transpired in Imperial Germany. The constitutional question was severely tested during the Zabern affair 1914. However, there never was a final legislative decision before the war broke out. The military considered themselves separate from the population. They worked for the Kaiser not for the Reichstag. Their loyalty was to the Kaiser not to Germany, not to Saxony, but sworn loyalty to the Kaiser. It was therefore of extreme importance that only the most trusted agents could be placed in a position of officership and respond to the whims of the Kaiser. iv

Bourgeois

Approximately 30% of the population was what you would call bourgeois. v

The bourgeois defined itself against the aristocracy. While we tend to think of this group as a middle class, the group was very wide and had many subdivisions. A common identity of these groups included a belief in property, hard work, achievement, recognition and rewards and the importance of rules. The bourgeois considered themselves a Bildungsbürgerturm or elite built on education. The bourgeois were enshrined in the institution of the family. The male figure was expected to be public and have a working life. The female was expected to devote herself to domesticity and teaching values to the next generation. Women, and children, were decidedly subordinate. vi

Moving from the bourgeois to the nobility was far less common in Imperial Germany than it was in Britain. In fact the amount of ennoblement was five times higher in Britain than in Prussia. Some of the most powerful bourgeois declined titles. Rather, the title of Commercial Councillor or its parallel councillor titles in professional fields were highly prized. vii

There was a large divide between the peasants of the countryside and the bourgeois. Even the richest peasants were set apart by manual labor, and a difference in education. Interaction between these classes was small. This divide was even more significant, if you realize that the bourgeois was split and that there was a lower level of bourgeois known as petty bourgeois. The term bourgeois, originally denoted a wide range of individuals from substantial business owners to small shopkeepers. This included also the “white collar” clerks. Eventually the term Mittelstand became applied to the lower level of bourgeois or petty bourgeois. The true bourgeois consisted of urban retailers and businessman who had some capital or means of production. The Mittelstand consisted of primarily small shopkeepers, clerks and supervisors, who existed near the margin. The Mittelstand prided themselves on titles, badges and status that separated them from the working class. viii

This rational was important for the Mittelstand. The small shopkeepers and artisans who had been protected by dealing with regulations in the old towns became known as the old Mittelstand. The white-collar workers became known as the new Mittelstand. Especially the new Mittelstand saw themselves as a class above the proletariat even though their economic circumstances were very similar. The Mittelstand was politically far to the right of the Socialist and the proletariat. Marxism preached elimination of the bourgeois which made the socialist political party (SPD) the “enemy”. ix

A look at low wages of different kinds of bourgeois workers you can see where the Mittelstand was squarely located.

Annual Wages in marks in 1913

Craftsman 1163.

White-collar workers 3753

Educators 2607 x |

|

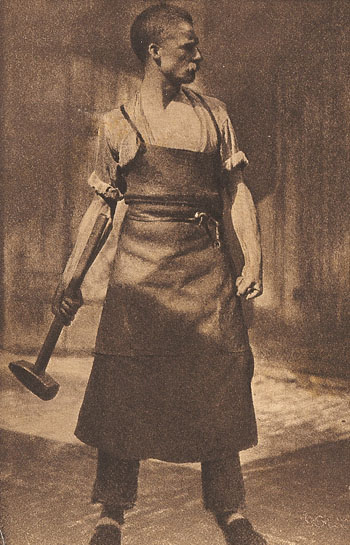

The Proletariat

The proletariat was about two thirds of the total population. Half of those realized less than nine hundred marks annually and had zero assets. xi The proletariat differed from the craftsman of the Mittelstand as they were paid by fixed wages. A craftsman would enter into contracts for the delivery of goods. The urban working-class was not exactly a fixed entity. Industrial personnel turnover rates of 50% to 100% were not uncommon. There was regularly a core of skilled workers that the employers wanted to keep that were surrounded by a sea of a floating labor force. The proletariat lived in residential segregation. Workers generally rented cramped inadequate living space. Two thirds of the family income was spent on food. What was left went for housing and utilities. Workers lived in constant fear of layoffs or any change in circumstances which would affect their ability to earn wages. The average work week was 75 hours as late as 1870. In certain industries the week was even longer. Eventually, the urban workday fell from 12 hours to 9 ½ hours just prior to World War I. Life expectancy for a man born in the 1870s was less than 37 years. For women it was 38 and half years. By the first decade of the 20th century, the life expectancy had risen to 45 and 48 for men and women. xii

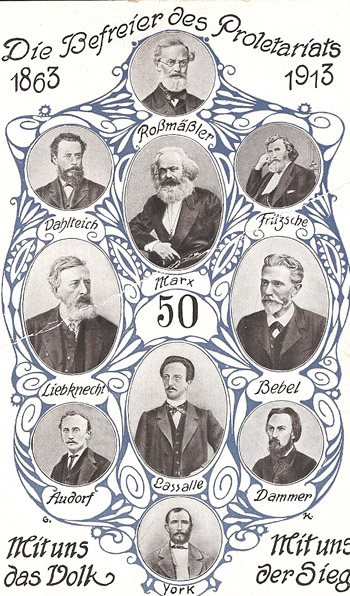

The proletariat existed entirely on the margin. Insecurity and lack of capital created a society that was barely capable of survival. Unemployment was rampant, with a third of the workforce expected to be unemployed at some time during the year. Homelessness was a major issue. 200,000 men a year were sheltered by the Berlin Homeless Shelter Association; in addition there were women and children. Unemployment was often the result of lockouts or strikes. Workers became involved in the labor movement and left wing socialist parties. Mobility between classes was very poor with little hope of self employment. xiii The Social Democrats (SPD) represented the working and un-propertied classes. They represented the opposition to the government and became classified as enemies of the state or “Reichsfeinde”. The growth in the Reichstag had come mainly from industrial centers. Theoretically, they were pledged to a program which includes the overthrow of the capitalistic state. xiv Fear of the Socialists had led to the anti-socialist laws of 1878 to 1890. These laws created a unity in the class struggle of those who considered themselves persecuted, in the lower class. When the laws were lifted the Social Democratic Party (SPD) had 100,000 members. By 1907 they had grown to a half a million and by 1914 there over one million members. One comparison indicated that this was more membership than the combined membership of the largest socialist parties in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Italy, Holland, Norway, Sweden Switzerland and Great Britain combined. xv

|

|

In some ways the mythical image of a well ordered German society seems to have been somewhat self delusional. Working-class urban districts were violent places where major riots took place in 1906 and 1910 over increases in beer prices. It was often said that Prussians moving to an urban area from the east initially bought a watch and then a gun. Many locations had a Wild West sort of reputation. In rural areas there were pitched battles to drive out Gypsies and for servants to revenge themselves on former employers. In some areas, both crimes against property and violent crime rates doubled in the decade before the war. Nonetheless the murder rate was about 20 times lower than Italian and Spanish rates and of the 30 to 40 murders in Berlin annually, half of them were infanticide. xvi

Male hostility to female emancipation was significant. Max Funke in 1910, declared that females were an evolutionary missing link between Homo Sapiens and less advanced species. The Civil Code of the early 1900s listed the husband as the head of the family and the guardian of the wife. xvii One half of all women who worked, worked in agriculture, with a third being domestic servants and no more than 1/6th worked in factories. Women were also expected to do all of the household labor, and they also did sewing at home on piece rates and did laundry and ironing as well as taking in boarders. xviii

Agricultural workers made even less. By 1913, the average agricultural wage was 682 marks a year. However both household servants and agricultural laborers generally got free room and board. xix Agricultural work painted a similar bleak picture. As more workers moved to urban locations. Chronic labor shortages amongst the peasants made family life difficult and resulted in extensive child labor. Agricultural laborers employed by the larger estates accounted for 40% of the working-class. They were poorly housed, poorly treated and poorly fed. Research has shown that more was spent on pigs than hired hands. Work weeks of 100 to 120 hours were common. To compensate for the labor shortages 500,000 migrant workers came to Germany annually from Poland. The migrants returned to Czarist Russia at the end of the season, causing friction. There were social and financial prejudices against the Polish migrant workers. xx

Individuals in the proletariat began working at age 15, after they finished Volksschule. Marriage regularly happened late in a worker’s 20’s, coinciding with the pinnacle of their wages. By the age of 40 a worker was in major decline. Income for the household was also increased while children who still lived at home worked. Poverty was a huge problem for the aged and old age began very early by our standards. Widows represented the largest single group of extremely impoverished individuals. xxi

Populations Movement

The population was moving. Generally the movement went from rural to urban and from the East and South up to the North West and West. By the First World War, 54% of the population no longer lived at their birthplace. xxii

External immigration was the first major drain on population. However, external emigration lessened the population in competition and actually helped the growth rate as workers stayed in demand. A quick look at migration shows that there were several waves from Germany in the 1850s, 60’ and 80’s. xxiii

Internal population movement was rapid. This was one of the many advantages of constitutional guarantees of unity everybody became a citizen of the state that they inhabited. However, it would seldom be a one-way journey or a once and for all solution. Between 1850 and 1870 population doubled in Berlin, tripled in Hanover, and quadrupled in Dortmund and Essen. By 1910, Berlin had gained another 250%. Urbanization did not mean the immediate disruption of a rural population. There was even internal migration that provided seasonal agricultural laborers. There was also seasonal migration seeking urban employment. Many rural workers found jobs in the industrial belt returning to their villages just twice a year. Workers attracted to urban sites left the Prussian State mines, which in turn were forced to recruit workers from the surrounding rural areas. In 1875, a full third of the Saar miners commuted on a weekly basis. The normal routine was to walk to work on Monday morning and return home on a Saturday evening. In these scenarios, workers had their feet in both the village and country. This was far from an ideal existence. Heavy burdens fell upon women, children and the elderly. Men were strangers in their hometown and were scorned and poorly housed, where they worked. xxiv

The urbanization of smaller cities followed similar patterns. Originally geographically restricted by medieval town walls, many of the walls were torn down, making room for the first urban suburbs. As growing towns expanded they annexed neighboring towns and incorporated before basic services were established. By the turn-of-the-century 60% of the Prussian population still drew water from wells. Sewage systems lagged behind terribly and cities utilized open gutters. It should not be surprising that housing was in great demand and short supply. Prices were high and conditions for the workers were abhorrent. Cramped quarters, with multiple boarders were the norm. In 1875 Berlin half of the houses had only one heated room and 20% of the city’s inhabitants were crammed in at five people to a room. Overcrowding, dampness, lack of proper ventilation, and primitive sanitary conditions all led to frequent outbreaks of infectious diseases such as cholera and typhus. These conditions paved the way for consumption and pneumonia which were the big killers. Infant mortality in the large cities was often higher than one third. xxv Central water supply was lacking in many major cities. By 1900 Berlin had 97% of its population supplied by central water. However, Posen had only 11% of the population supplied. xxvi

The Army contributed to the migration. Soldiers who were stationed in garrisons in urban areas often would not return to the countryside unless they had an existing relationship or were due to inherit some land. It was generally believed that working conditions were better in the city; hours were shorter and pay significantly higher. xxvii

Political Parties

A complete discussion of political parties is far outside of this little article however the Empire considered the Socialists and their party the SPD as the enemies of the Empire. A major push of the SPD was to eliminate the Prussian three-tier system which gave advantages to the upper classes in Prussia. There was universal suffrage in the elections of the Reichstag. Nonetheless, the strength of the SPD continued to grow and in 1912 they were the largest bloc in the Reichstag. The proletariat was heavily involved in the SPD as many workers saw this political angle as the only way up. The bourgeois and the aristocracy were against the changes demanded by the SPD as they wanted to keep the status quo.

The Army Corps Military Districts

A last little issue that needs to be understood, underneath the hierarchy the army itself was organized into Corps. There were 21 Corps that were active in the Prussian army. In addition, Bavaria maintained its own Corps structure while the armies of Saxony and Wurttemberg became part of the Prussian army corps structure. The Saxon army was concentrated in XII Corps and XIX Corps, while the Wurttemberg army was in XIII Corps. There was also a Guard Corps. The Corps commanders were extremely powerful individuals, who administered and recruited from their regions and reported directly to the Kaiser or the King of Bavaria in the case of the three Bavarian Corps.

These geographic corps areas were known as military districts. Military districts operated alongside civilian bureaucracies with no yielding to the jurisdiction of the public structures. The boundaries of military districts did not correspond to the boundaries of state governments. Fifteen military districts crossed the geographic boundaries of state governments. Many others encompassed two or more states while the XI Corps covered eight of the smaller states as well as a Prussian area. xxviii

Each of these Army Corps districts were subdivided into four or five brigade districts. Landwehrinspektions were alternative higher headquarters that replaced brigade headquarters in the more populous (and popular) areas of the empire. The commander of the Landwehrinspektion was a Generalmajor. Each district was further subdivided into two or three Landwehr-Bizirke. Each Landwehr-Bizirke had a small permanent staff. The Corps commander was responsible for tactical -- -- not technical -- -- training of the soldiers in his region. Each Corps was administered independently. In Prussia alone there were 212 Bezirkskommandos (or Landwehr-Bizirke) with assigned personnel of about 6000 folks. Landwehr-Bizirkes were either subordinated to an infantry brigade headquarters or a Landwehrinspektion. xxix

In peacetime the commanders were the commanders of the active corps. However when those corps deployed, control the military district fell to the deputy commanding general. The deputy commanding general was responsible only to the Kaiser. Therefore the deputy commanding officers became rulers of independent areas as much as commanding generals were independent satraps. They could and did resist attempts of both military and civilian authorities to impose policies or common practices. xxx

Why This Matters to Universal Military Service

This discussion above sets the stage for the requirement for universal military service as set forth in the Wehrordnung. xxxi I have shortened it significantly but wanted to leave the reader with an understanding that the lowest class lived entirely on the margin and that the bourgeois established the culture that is always read about. Taking it to a further limit the work of Jeffrey Verhey indicates that with few exceptions, all published works and media were controlled by the bourgeois before, during and after the war. The proletariat was too busy trying to scratch out survival and the socialist politicians were constantly under attack by the establishment. Socialist media was discredited and had a reputation for propaganda. The different political parties offered a large amount of differentiation however; you were either for the Reich or part of the SPD and against it. You were a citizen of one of 25 different states within the empire however for recruiting and Army purposes you were a part of the Army Corps Military District. The area you lived in was represented by someone in the Reichstag but the army that was recruiting you answered only to the King of Prussia or Bavaria.

Citizens were categorized by class designated by the year in which they were born (Jahrgang). So the class of 1892 for instance would be the recruiting process in 1912 at the age of 20 (Jahresklasse). The class consisted of all men who would attain the age of 20 during the year. This is often confused because the French system used the year in which they reported in. xxxii

Go to page 2

i Deutsche Wehrordnung vom 22 Nov,1888, Max Galle Verlag Berlin, 1915.

ii Berghahn,Volker, Imperial Germany,Berghan,Oxford, NDN,pg 6-7.

iii Frevert,Ute, A Nation in Barracks, Berg, Oxford, 2004, pg 155.

iv Silverman, Dan, Reluctant Union, Penn State Press, London, 1972.

vi Blackbourn, David, History of Germany 1780-1918,Blackwell, Oxford 2003 ,pg 157-162.

vii Blackbourne, pg 279-280.

viii Blackbourn, pg 163-165.

ix Feuchtwanger, Edgar, Imperial Germany 18501918,Routlege, New York,2001, p,g 100-102

xii Blackbourn, pg 165-168, 266-269.

xiii Blackbourn, pg. 273-274.

xiv Fife,Robert, The German Empire between Two Wars, Chautauqua Press, Chautauqua, NY, 1916, pg 125-126.

xv Blackbourn, pg. 312-313.

xvi Blackbourn. Pg. 282-283.

xvii Blackbourn, pg. 281.

xxi Blackbourn, pg 168-169.

xxii Berghahn, pg. 43-46.

xxiii Blackbourn, pg 147149.

xxiv Blackbourn, pg. 149151.

xxv Blackbourn, pg. 151-157.

xxviii Chickering,Roger, Imperial Germany and the Great War, Cambridge, Cambridge,2004,pg 33.

xxix Handbook of the German Army in the War, 1918, pg.15.

xxx Chickering, page 33 to 34.

xxxi Deutsche Wehrordnung vom 22 Nov,1888, Max Galle Verlag Berlin, 1915.

xxxii Notes on the German Army in the War, Translated at the Army War College, Government printing Office, Washington, 1917, pg. 28.