The Free State Artillery Pickelhaube

MC Heunis—O.V.S.A.C. Study No.9

JUL-SEP 2004

|

Little Prussia in the Veldt

|

||

|

If you are interested in receiving any of the OVSAC’s other study pieces on Boer War artillery and re-enactment, please contact the Officer of Administration, MC Heunis at kruppgun@yahoo.co.uk

|

||

| Introduction

Very few relics of military history are as distinctive and striking as the German Pickelhaube. After Prussia’s quick victory over France in 1871 the spiked black leather helmet became a symbol of military strength, moving several other armed forces around the world to imitate the Prussians and to adopt some form of spiked helmet. One of the most interesting states to do so was the small Boer republic of the Oranje Vrijstaat.

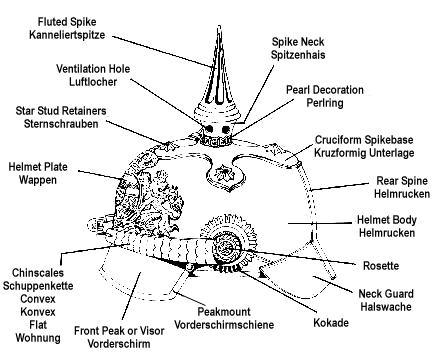

History of the Pickelhaube In 1842 the Prussian King, Friedrich Wilhelm IV, introduced a tall spiked helmet for the majority of his foot troops. The helmet with its sharp spike was designed to create the image of a highly aggressive military force. Officially the head dress was called a Helm, but in typical military style the soldiers who wore it came to refer to it as Pickelhaube, which literally means “Pick Cap”. |

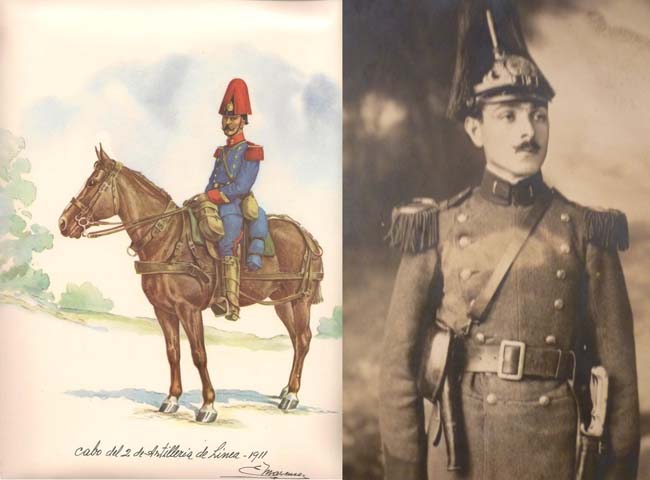

Drawing showing the main parts of a Pickelhaube.

|

|

| The original helmet (Model 1842 or M1842) consisted of a shell onto which a square front and rear visor were sewn. The shell was formed by pressing a piece of steamed leather through a large mould. After this the helmet was covered in many layers of black lacquer until it could be polished to a bright finish. The helmet was equipped with a brass reinforcing trim piece on the front visor and a brass spine at the rear. The completed helmet was almost 38cm tall with a cruciform spike base and a large gilded brass helmet plate. For most units the helmet was decorated with a tall spike, but artillery units wore a ball final to represent a cannon ball or Kugel. | ||

| The spike was ventilated by two holes on the spike neck. Around the neck of the spike was a brass decorative Perlring, literally, a “ring of pearls”. Convex brass chinscales were worn by all ranks and were secured to the helmet with a long bolt with a brass head. The spine was secured to the helmet by external bolts. Originally the front plate was also secured by two bolts that passed through the front of the plate, but in 1843 this was changed to two bolts soldered to the reverse of the plate. On the right side of the helmet a single leather cockade (Kokarde) in the Prussian national colours of black/white/black was worn under the chinscales.

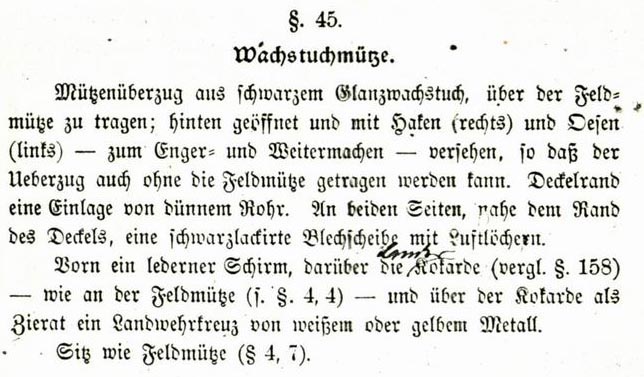

Shortcomings of the original design were immediately evident, but the King had an irrational attachment to his creation. The helmet was so tall that some observers even proposed that soldiers should carry their mess kits inside the top of the helmets! Truly impractical, even by 19th century standards, it was unpopular with the troops and had the tendency to fall off during drill. The continued dissatisfaction with the design of the Pickelhaube necessitated several developmental changes during the following years. The first major change occurred in 1856, when the convex brass chinscales were changed to flat brass chinscales for all infantry units (M1856/57). Calvary and field artillery units however continued to utilize the convex chinscales. At the same time, the leather Kokarde was changed to a smaller sheet metal version. In 1857 and again in 1860 the helmet’s height was also reduced to make the helmet less unwieldy and more practical for use. Experience gained in Prussia’s wars against Austria and Hanover in 1866 and against France in 1871, indicated that the Pickelhaube’s design required further refinement, resulting in the M1867 and M1871 helmets. To simplify production and reduce the cost of manufacturing, the cruciform spike base was changed to a round base, while the square front peak was changed to a rounded form. The round spike base was secured to the top of the helmet by four retaining studs. On the M1867 the rear spine was removed to reduce the amount of brass used in construction, but was reintroduced in the M1871 as the helmet proved to be too weak without it. The new spine was secured to the helmet with hidden bolts soldered to the underside of the spine. |

In January 1871, following the end of the Franco-Prussian War, the new German Empire was founded. The Pickelhaube was adopted by most units in the empire; each of the German Kingdoms, Dukedoms, Earldoms, Free Cities, etc., having its own unique helmet plate and state Kokarde. Many other countries also adopted some form of spiked helmet during this period, including Britain and the United States. Some more changes to the German helmet were introduced in 1887 to reduce the amount of brass used in its construction. The front peak trim was removed, and a ribbed edge was pressed directly into the leather. For infantry and foot artillery units, the brass chinscales were changed to a leather chinstrap for enlisted ranks. For the new leather strap the threaded post and bolt used to secure the chinscales was changed to a loop and hook system. The spike was reduced in height, and the Perlring on the spike neck was removed from enlisted men’s helmet spikes. Officers, NCOs and cavalry units however continued to utilize the Perlring.

A ball-pattern Perlring on a Kugelhelm. |

|

|

The M1891 chinstrap retaining loop and post.

|

In 1891 the loop and hook system used to hold the leather chinstrap in place on the M1887 helmet was replaced with a loop and post arrangement. A new double buckle leather chinstrap was used and the end of the strap was fitted with a brass loop with a “V” cut. The loop was designed to fit onto the corresponding M1891 post, keeping it secure but allowing easy removal. The front peak brass trim was also reintroduced as it was found that its omission weakened the helmet significantly. The M1891 further brought about a final reduction in the height of the helmet, giving it a more domed appearance – a remaining feature on all future Pickelhauben. |

|

| In 1895 the rear spine on all enlisted men’s helmets was equipped with a ventilation hole near the base of the spike. The vent was fitted with a small sliding cover, which enabled the user to increase or decrease the flow of ventilation in the helmet. To further aid in ventilation, the two vent holes on the spike neck were increased to five. The soldered bolt and nut system used to secure the front plate onto the helmet was also changed to a soldered loop that passed through corresponding holes on the front of the helmet.

In 1897 a new Reichs-Kokarde in Red-White-Black, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Kaiser Wilhelm I, was introduced for all ranks of the German Imperial Army. The new Kokarde was worn on the right side of the helmet, while the different state Kokarden were moved to the left. After the outbreak of the First World War, the shiny brass and German silver fittings on enlisted men’s helmets were changed to steel and were painted in various shades of grey. This was done primarily to free up brass and silver for the war effort and to make the wearer less conspicuous. Another effort to make the wearer less visible was to make the spike removable. The new pattern spike was slotted and fitted into a corresponding bayonet-style lug on the round spike base. These changes brought about the final and most common Pickelhaube, the M1915. |

Due to the Allied blockade of Germany, a shortage of leather (imported from Argentina) resulted in the German army making helmets from Ersatz (replacement) materials. Manufacturers of kitchen utensils were called on to turn out helmets of thin steel and tin. As the war continued, many other materials were also used, including felt, vulcanised fibre, cloth covered cork, and even paper mache. Some of these helmets were equipped with brass and silver fittings as manufacturers used up remaining parts from pre-1915 helmets, while other carried M1915 grey steel fittings, or even a combination of both.

The end of the Pickelhaube had dawned. Neither the leather nor the Ersatz steel Pickelhaube helmets offered any protection in combat, and therefore the Army Medical Corps demanded that new head gear should be developed to reduce the number of head wounds. In February 1916 a steel helmet (Stahlhelm) was introduced in small numbers to the front line troops engaged in the Battle of Verdun. The resulting reduction in the number of head wounds suffered by the soldiers lead to the general replacement of the Pickelhaube. In the end the German army used Stahlhelms in greater numbers, but it was the Pickelhaubethat left a lasting impression on world history. |

|

| The Free State Artillery Pickelhaube | ||

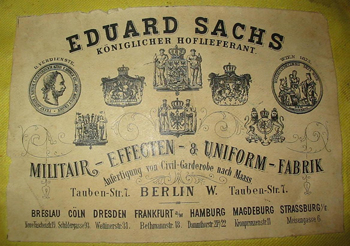

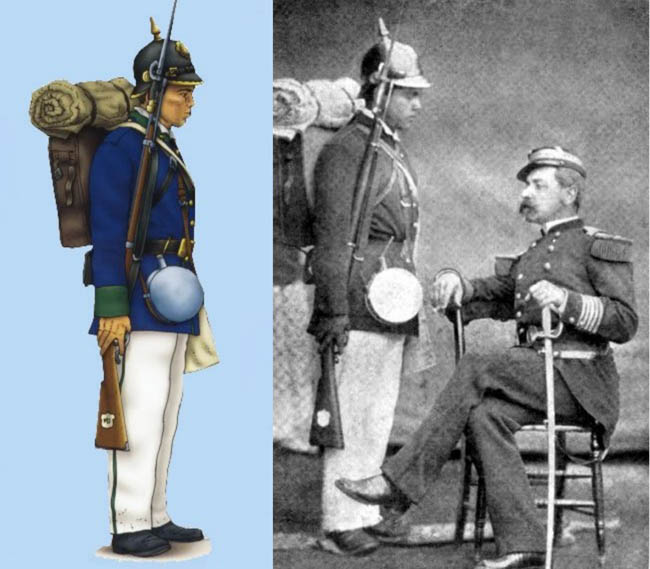

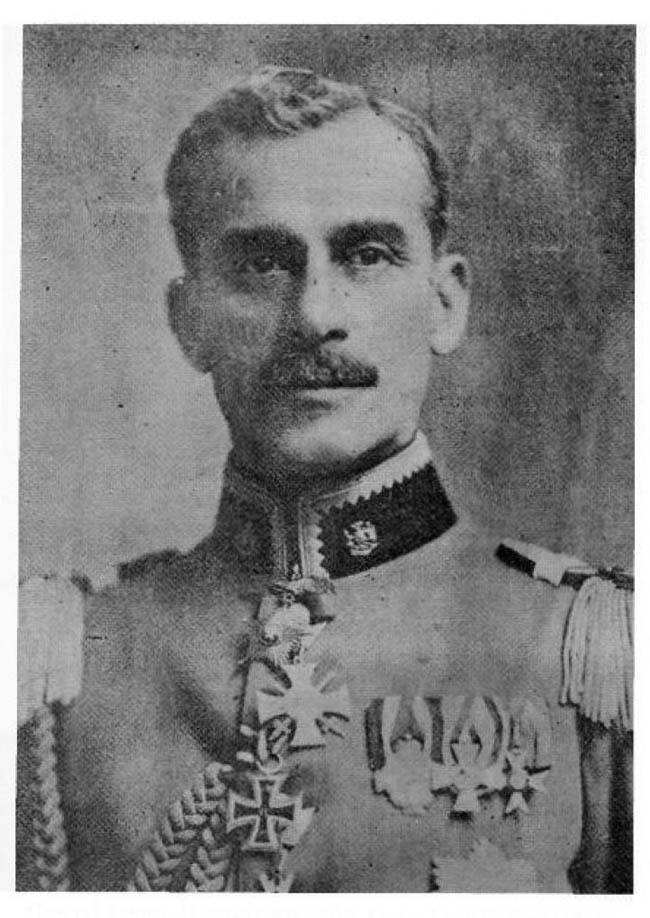

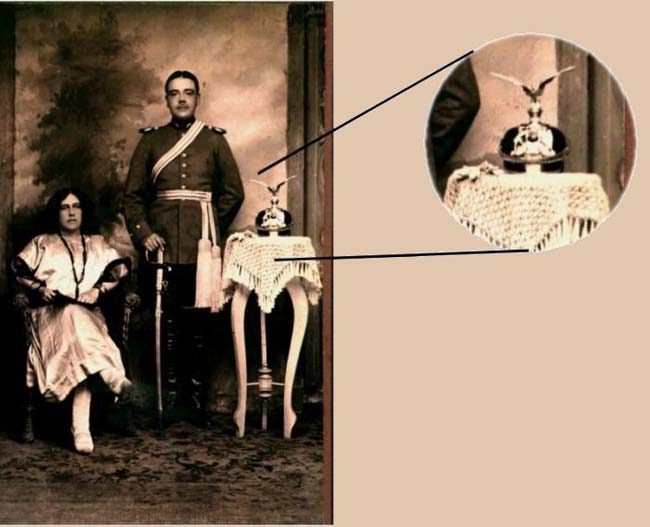

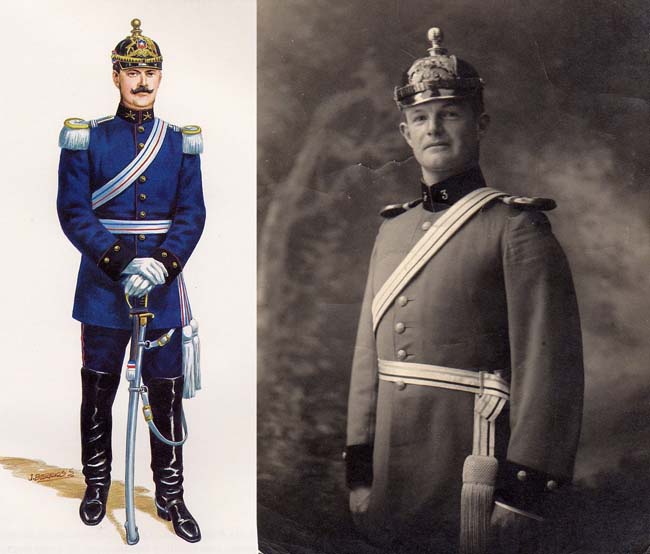

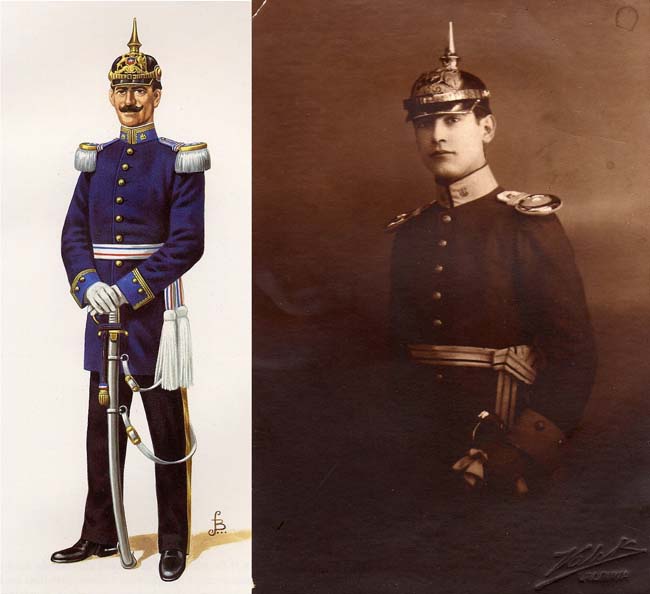

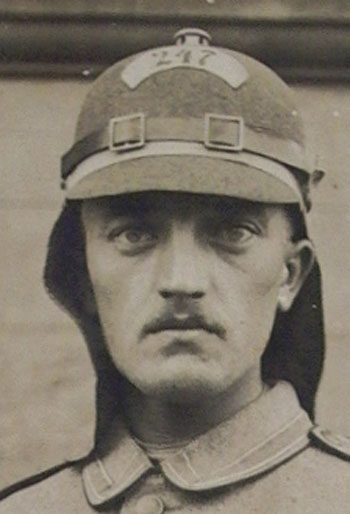

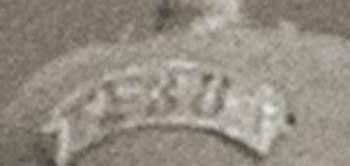

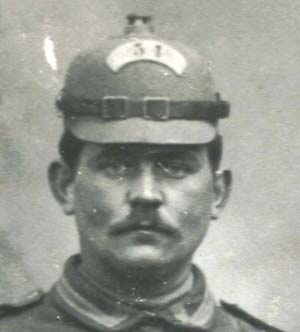

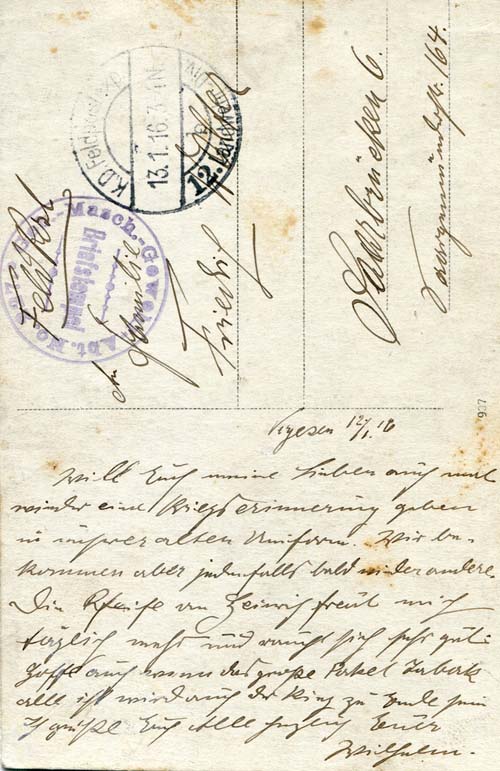

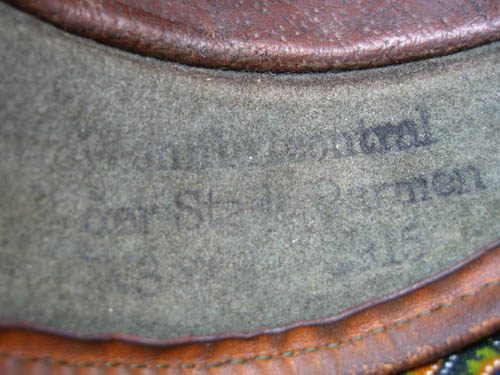

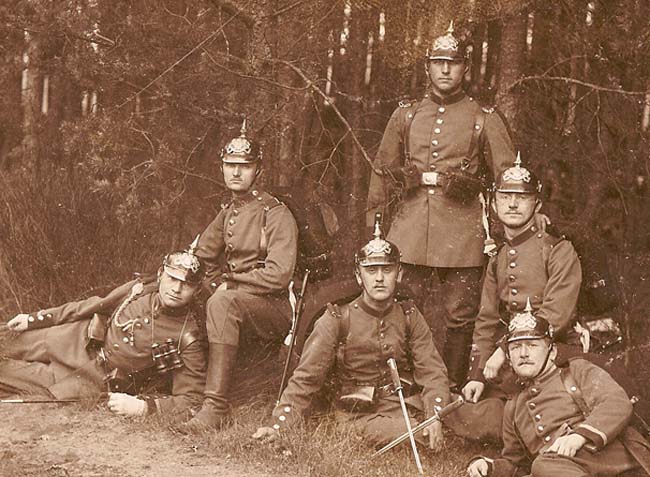

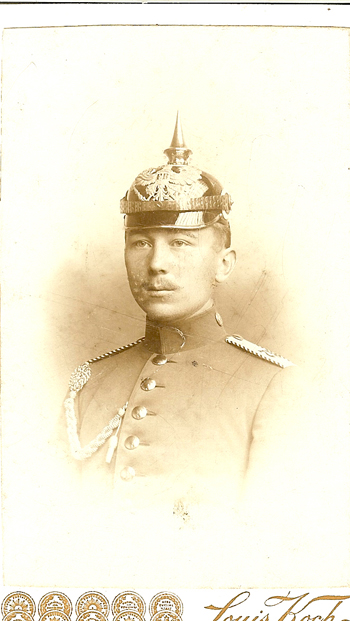

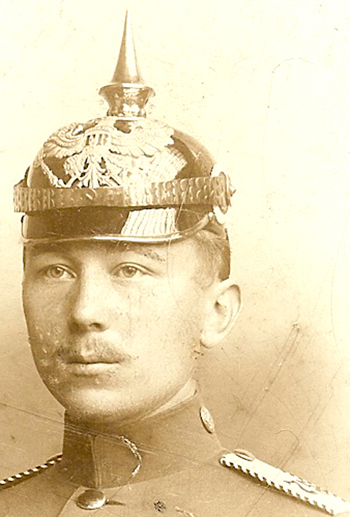

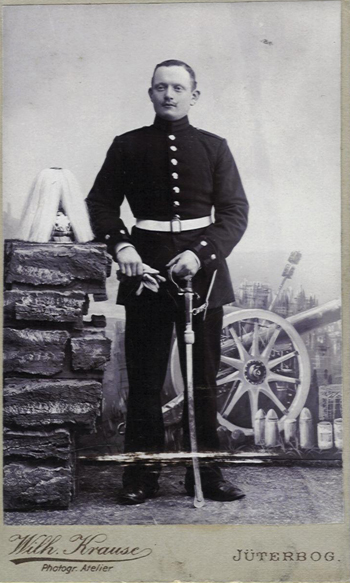

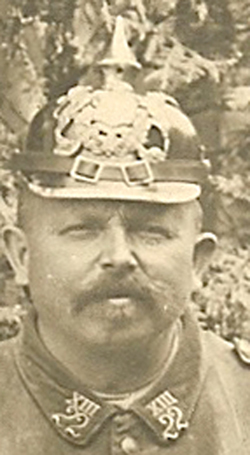

| In November 1880 FWR Albrecht, formerly of the 4th Prussian Guard Artillery of Berlin and a veteran of the Franco-Prussian War, was appointed as captain and commanding officer of the Oranje Vrijstaat Artillerie Corps (OVSAC). Under his competent leadership the OVSAC was to undergo a major turnabout. (Not so sure… 4. Garde-Feldartillerie-Regiment was not formed until 1899 and in any case was based in Potsdam. Albrecht was not a former Prussian Artillery Officer as claimed by some. I believe Albrecht was a gunner in the Franco-German War and probably rose to NCO rank before leaving Prussian service.Joe) Earlier Free State Artillery uniforms and helmets were based on those of the British Royal Artillery, but in 1885 Albrecht started to introduce Prussian style uniforms. The new uniforms resembled the dress of the 2nd and 4th German Guard Artillery regiments and were imported from Germany. At least two different suppliers were used, CF Wulfert and Eduard Sachs, both Berlin based military effects and uniform factories. The switchover from British to German uniforms was gradual and various photographs show OVSAC Gunners wearing Prussian style tunics with the earlier British style helmets. Exactly when the Pickelhaubemade its first appearance in Bloemfontein is not known, but it is suspected to have been in the late 1880s or early 1890s. |

Major FWR Albrecht in officer’s undress.

|

|

|

Eduard Sachs’ label on the inside of a surviving OVSAC Pickelhaube carry case preserved at the War Museum of the Boer Republics. |

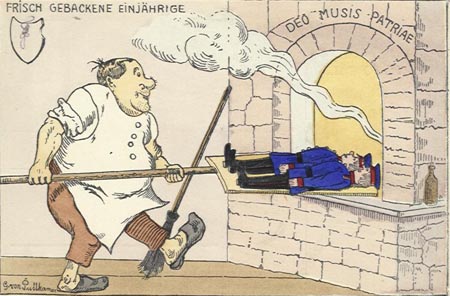

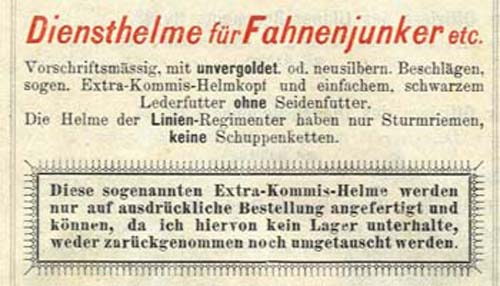

Because the Free State’s helmets were privately purchased they differed from the standard German army issue Pickelhaube. In Germany private-purchase pattern helmets were referred to as Eigentums-helm or also known as Extra-helm or Eigetumsstück. Eigentum translates to “property”, indicating the item was privately purchased by an individual. In the German army any soldier was allowed to purchase an Eigentums-helm, but it usually depended on the wealth of the individual and therefore they were mostly worn by the better off One-Year Volunteers (Einjährig-Freiwilliger) and Officer-Candidates (Fähnrich). The Eigentums-helm was of a better quality than the standard army issued helmets and often incorporated style and comfort features normally only found on helmets issued to officers. | |

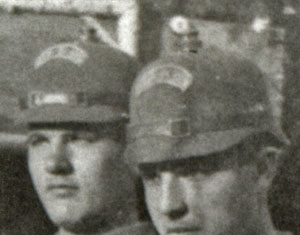

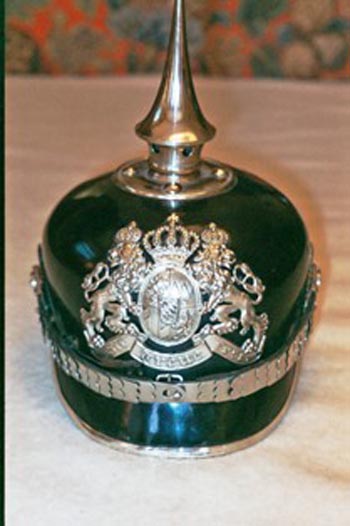

| Helmet Construction: The Free State helmet consisted of a domed shell, similar to the German M1891, with a round front and square rear visor. The helmet was finished in a bright polished black, while helmet fittings such as the front plate, ball final and base, front visor trim and rear spine were manufactured from gilded brass. |

||

|

Front Plate: The one-piece stamped gilded brass front plate was of the same design as those worn on the earlier Royal Artillery pattern helmets. It consisted of a large eight-pointed star with a Free State coat-of-arms and scroll (bandeau), reading “Oranje Vrystaat”, surrounded by a laurel wreath. The stamped plate was secured to the front of the helmet by two threaded bolts soldered to the reverse of the plate and passing through the front of the helmet before being fastened by two flat square brass nuts. |

||

|

Kokarden: Unlike some researchers have claimed in the past, only one Kokarde was worn under the chinscales; on the right hand side of the helmet. The Kokarde was manufactured from one piece of metal with a small centre hole (pre-1891 design) and finished in enamel paint in the colours of the lines on the state flag, white/orange/white. As was the case in the German army, the Kokarden on the Free State Artillery helmets seem to have differed according to rank. Surviving examples show at least two types of Kokarden in use: |

OVSAC officer’s Pickelhaube, reportedly that of Major Albrecht. National Museum, Bloemfontein.

|

|

In the German army NCO Kokarden were similar to those worn by Privates, but had an additional ring with a distinctive diagonal ribbing. It is not known whether this was also implemented on the Free State Artillery helmets and to date no surviving examples could be found. |

||

|

Private (left) and officer (right) pattern Kokarden. War Museum of the Boer Republics, Bloemfontein.

|

|

|

|

Right and left hand side of OVSAC officer’s Pickelhaube. War Museum of the Boer Republics.

|

|

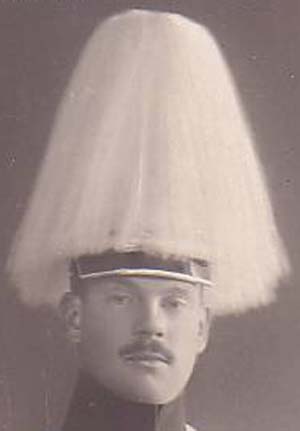

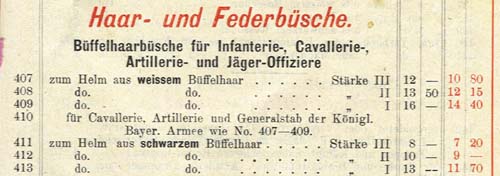

| Kugel: Being an artillery unit, the helmets of all ranks carried a brass ball final with a round base. In the German army the height of helmet spikes was set at 95mm for officers and 85mm for all other ranks. On privately purchased helmets, like the ones imported by the Free State, the spikes generally tended to be taller and of a better quality. The ball spike top was removable to enable an orange and white falling horse hair plume (Trichter and Haarbusch) to be mounted to the helmet for full dress purposes. | ||

|

Horse hair plume and Perlring detail on OVSAC officer’s helmet. War Museum of the Boer Republics.

|

|

| Perlring: The neck of the ball spike on Free State helmets was decorated by a brass Perlring. Privates and NCOs wore the regular ball-pattern Perlring, while Officers’ helmets utilized a more elaborate pattern sometimes referred to as the “Dart and Egg” pattern.

Base Mounts: The ball spike base on Private’s and NCO’s helmets was secured to the helmet shell with four domed threaded screws and was fastened on the underside with flat square brass nuts. Officer’s helmets utilized small 8-pointed stars on a threaded post to secure the spike base. On the surviving officer’s helmet of Lt Johan Böning, in the collection of the War Museum of the Boer Republics in Bloemfontein, the ball spike base is held in place by three domed and one star screw. Lt Böning was a one-pip lieutenant, but it is doubted whether his rank was indicated by the number of stars on the base and normally all four screws would have been stars for all officer ranks. |

Chinscales: Like the German Guard Artillery units, all ranks of the Free State Artillery Corps wore convex chinscales. The chinscale strap consisted of two halves with a small lug connecting the two thinner ends together. The other wider ends of the strap were secured to the helmet with a Rosette which had two split prongs that were bent back inside the helmet.

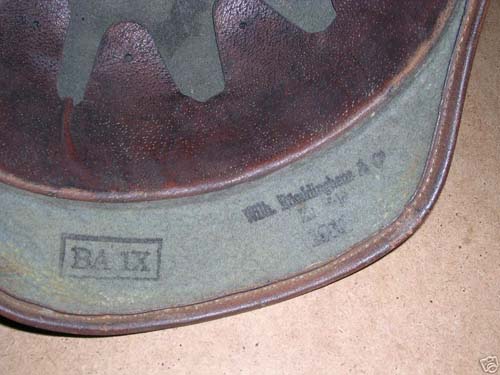

Visor and Trim: Visors on privately purchased helmets were made from higher quality leather and sewn to the helmet shell with fine thread. The visor trim was also of a higher quality, around 6mm wide, curved in shape and considerably thinner than the German army issue. Rear Spine: On the rear of the Free State helmet a pre-1895 plain brass spine ran from the spike base to the bottom of the rear visor to add strength and rigidity to the helmet body. The spine was secured to the helmet with hidden bolts soldered to the underside of the spine and fastened with flat square brass nuts on the inside of the helmet. Privately purchased rear spines did not incorporate the M1895 spine ventilation hole and sliding cover and were of a higher quality than the German army’s pre-1895 spine. |

|

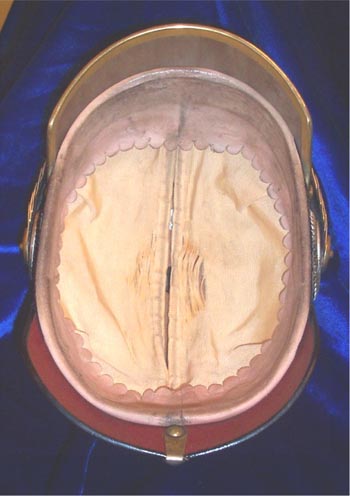

Inside and back of OVSAC Pickelhaube showing square nuts, square tongue liners and pre-1895 spine.

|

|

|

| Liners: Free State helmets were lined with squared leather tongues. This pattern was commonly encountered on Eigentums-helm and was referred to as the “Extra” pattern. The leather was of a higher quality and it was felt that this style of liner afforded more comfort than the rounded tongues of the standard German army helmet. As far as could be ascertained Free State helmets did not have cloth liners on the undersides of the visors as was the case with some German officer’s and privately purchased helmets. | ||

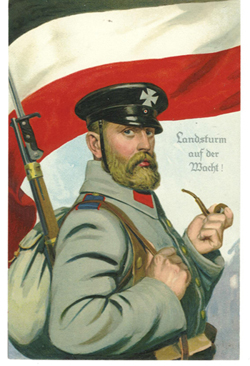

| President Brand Rifles |

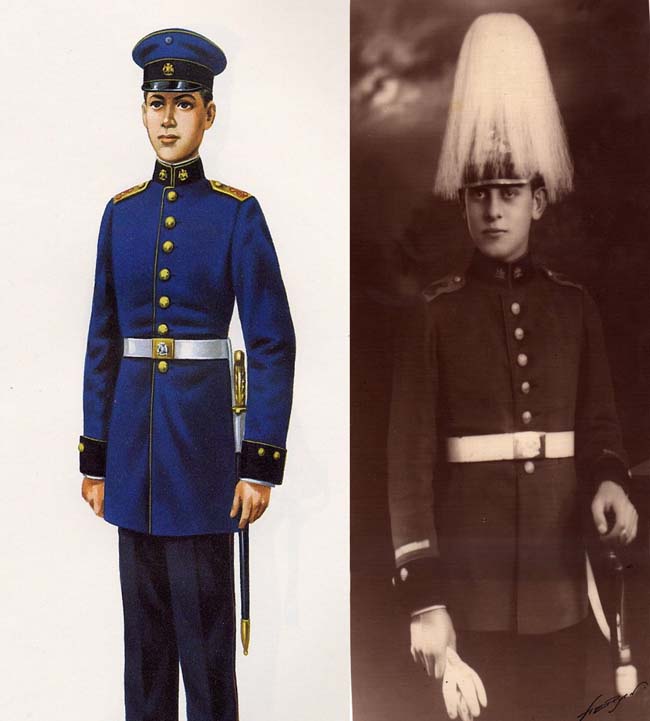

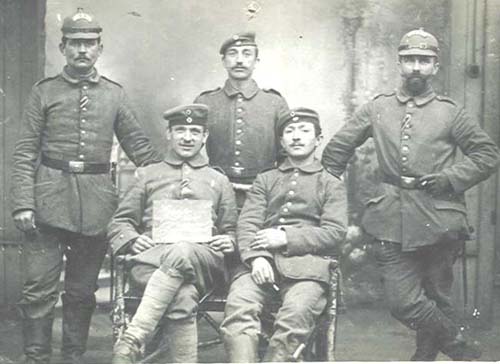

The Free State Artillery Corps was not the only Free State military unit to wear the Pickelhaube. In September 1888 a volunteer unit, the President Brand Rifles, was founded in Bloemfontein to “exercise the young burghers of the City Bloemfontein with rifles”. |

|

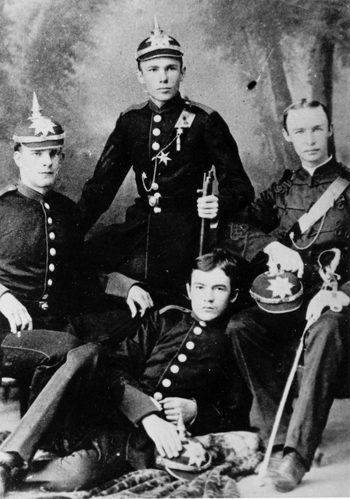

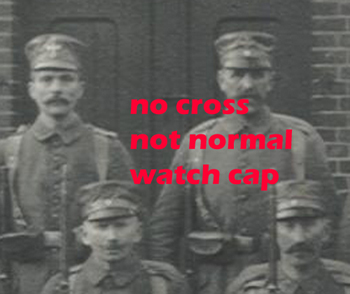

Four young members of the President Brand Rifles showing their “unpopular” spike-topped Pickelhaube helmets. |

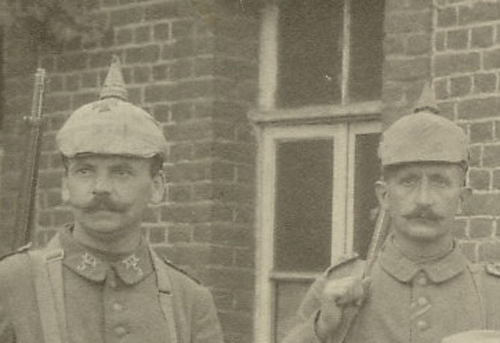

This unit’s uniforms were also made by CF Wulfert of Berlin and were received in February 1889. The helmets consisted of a domed Pickelhaube similar to the pattern worn by the Artillery Corps, but with a smooth spike in stead of the ball final. Unfortunately none of the original helmets are known to have survived, but contemporary photographs show an eight-pointed star helmet plate (not the same as worn by the artillery), a Perlring on the spike neck, a round base as well as chinscales.

Initially the German uniforms were received well, but since most of the townspeople and members of the unit were of a British background, the Pickelhaube soon became unpopular. A local newspaper, The Friend of the Free State wrote: “…the helmet is the only thing which does not give general satisfaction, it being locally described as a flat Bismarkian arrangement”. By 1890 the members of the unit openly spoke out against the uniforms and another Free State newspaper, De Expressreported: “…at present a rifleman in full dress looks like a bad cross between a flunkey and a railway guard.” |

|

| Photos of the President Brand Rifles seem to indicate that the Pickelhaube helmets were later replaced with more British-looking pith helmets. One set of photographs of President Brand Rifle NCOs show white tropical cork helmets decorated with the same fittings as those found on the unit’s Pickelhaube, suggesting that the fittings on the Pickelhauben were removed and simply fitted to the new cork helmets. | Summary

As with most “impractical” military things, the Pickelhaube did not see wide scale use in the Free State and no recorded instances of Free State artillerymen wearing their helmets during the Boer War could be found. Nevertheless the adoption of these helmets remains a very interesting and often overlooked part of South Africa’s military history. It is unfortunate that only a hand full of Free State helmets are known to have survived and it is hoped that more looted examples will one day be discovered in overseas collections and museums. |

|

| Acknowledgements:

We would like to thankMr Tony Schnurr for the permission to utilise the extremely useful information from his “Kaiser’s Bunker” web-site articles on Pickelhaube evolution and rank identification.

Sources:

Photo Collections Consulted:

Uniform Collections Consulted:

|

||

Where Are the Enlisted Landwehr Crosses?

Where Are the Enlisted Landwehr Crosses?

Where Have All the Landwehr Crosses Gone?

Joseph P. Robinson.

3 December 200

This might sound like a song from Peter, Paul and Mary but while I was working on Ersatz things, this kept bothering me. Why are landwehr crosses on enlisted helmets so rare? I am not talking about rare as in almost never seen. I am saying that the numbers do not add up. By all rights there should be a heck of a lot more of these.

Have you ever thought about the numbers involved in the mobilization of the German army in 1914? The Germans initially had a peacetime army of about 700,000 people. Once mobilization began the numbers were a lot larger. Total of the eight field armies; 1,637,000. In addition there were the following other groups. Ersatz Gruppe in Lorraine (6 Divs, 1 Brigade) 120,000. Army of the North (Danish border) 60,000. Border Fortress Commands( very roughly equivalent to 6 Divisions) 120,000. Landwehr Corps 1,2,3,4 in the static defense of Eastern Germany border 160,000.

Total: 1,637,000

120,000

60,000

120,000

160,000

2,097,000 Field Army Requirement.

So in general terms, we have 2,100,000 soldiers split up basically like this:

Active Units : 54% active duty soldiers

46% Reserve soldiers.

Reserve Units: 1% active duty soldiers

44% Reserve soldiers.

55% Landwehr soldiers from the 1st Ban

Landwehr Units: 62% Landwehr soldiers from the 1st Ban

38% Landwehr soldiers from the 2nd Ban

While the exact numbers are not known certain generalizations can be made. Most but not all of the eight armies had existing helmets of one sort or the other. Some of these were older and did not match exactly. There were no existing reserve infantry regiments or landwehr regiments. However, some were formed on an annual basis to support the training requirements of specific corps orders. The key question of this article is: if there were over 2 million soldiers and most of them are either landwehr or reserve; why are landwehr crosses on enlisted helmets so rare?

For the officer corps this is not a problem. There were different methods to gain a commission either as an officer of the active force or to get a commission as a reserve officer. Reserve officers would transfer to the landwehr upon their request, and the attainment of the adequate age.

Pictures such as this are common, helmets frequently found, and documentation of unit histories and rank lists abound. It is true that this individual who received his commission in the reserves was not considered an equal to the active officers by their own clique. There were specifically different wappen for Prussian officers of the active, reserve, and landwehr forces. The same cannot normally be said for enlisted soldiers. Understanding these differences in the Prussian eagles is useful. the active eagle looks like this:

The reserve eagle is similar but omits the bandeaux on the wings. These are sometimes used for Beamte without a cross.

Two key features of this Wappen are the large letters FR a the center of the Eagles chest and the Landwehr cross in a lower position.

Two key features of this Wappen are the large letters FR a the center of the Eagles chest and the Landwehr cross in a lower position.

The Landwehr Eagle has no large letters and the Landwehr cross is in the center of the chest or the upper position.while a distinction in Eagle was obvious for officer helmets there was no reserve eagle for enlisted soldiers. Regardless of the eagle, the Landwehr cross should seldom be in the lower position for enlisted helmets. Examples like the picture below exist.

The Landwehr Eagle has no large letters and the Landwehr cross is in the center of the chest or the upper position.while a distinction in Eagle was obvious for officer helmets there was no reserve eagle for enlisted soldiers. Regardless of the eagle, the Landwehr cross should seldom be in the lower position for enlisted helmets. Examples like the picture below exist.

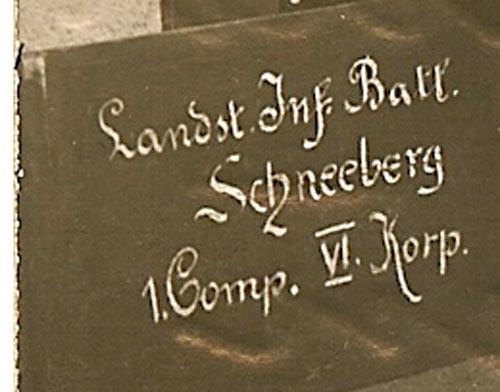

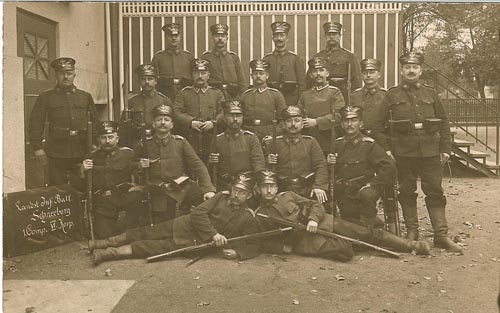

Before the war, reservists and landwehr enlisted soldiers had specific training requirements. They had no helmet at home. In the annual Verordnungsblatt the requirement for a certain amount of soldiers to fulfill the training requirement were published. The Bezirkscommando responding to a tasking from the army Corps district sends out notifications to individual soldiers to report for that years maneuvers. There are no landwehr units or reserve units. So they are created for the exercise. These are called Übungs units. Here is a picture of a 1911 Übungs unit and as usual, they have no landwehr cross on the helmet.

When reservists showed up they were organized into Übungs units and drew their equipment from somewhere. Did the Bezirkscommando have a store? Did the Regiment maintain a stock for training? So what helmets exactly had landwehr crosses on them? What about reserve soldiers filling up active units? If you are a reservist reporting in for your training did the company Kammer have helmets with landwehr crosses on them? A humor book from 1888 tracks induction of any Landwehr Ubung soldier. This gentleman drew his helmet from the company Kammer that was supporting his training. Therefore, he had no Landwehr cross.

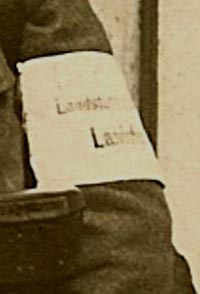

During the war the numbers imploded. Scores of group pictures exist was no landwehr cross. In addition, most pictures that have pickelhaube show them are under a cover. In fact certain War Ministers published directions to use helmets without certain articles or with the wrong color fittings, knowing full well that they would be covered by an Uberzug. Early Uberzugs had markings that could determine a units origin. There were landwehr crosses used by some of the mobilizing troops, and in fact were used on some of the Ersatz helmets like the example shown below.

The problem is simple. Based on the number of reservists and landwehr soldiers one would expect there to have been more crosses. Obviously their application was spotty and probably based on availability. Clearly not all of the reservists and landwehr soldiers before or during the war wore the cross. The mysteries continue.

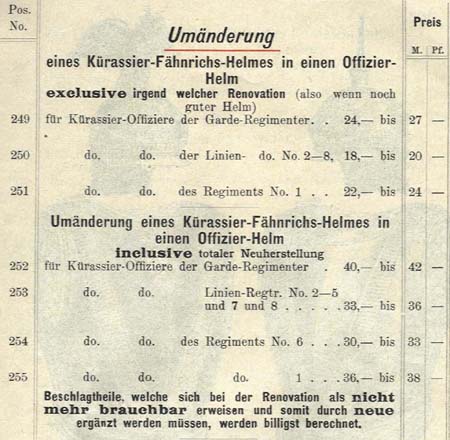

Upgrading Kürassier Helmets

Upgrading Kürassier Helmets

Joseph P. Robinson.

December 1, 2005

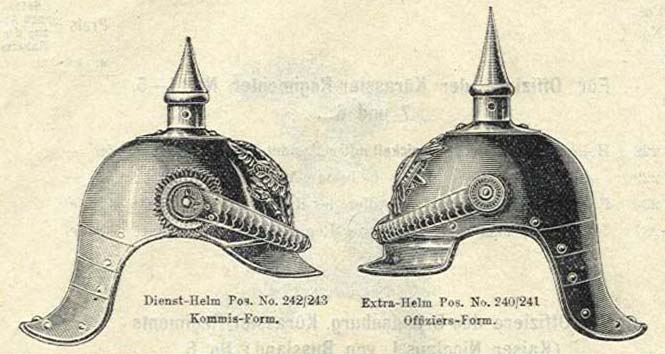

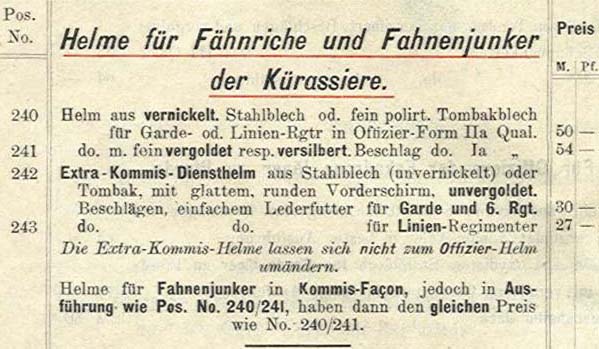

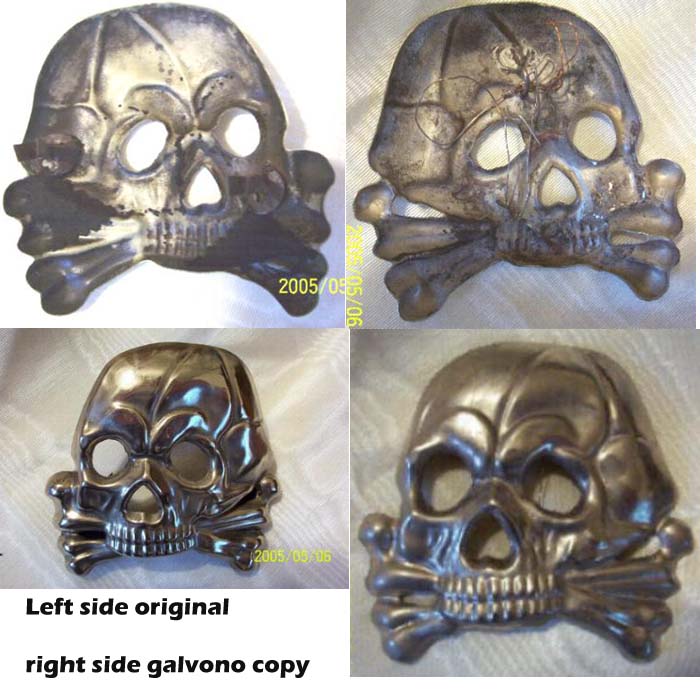

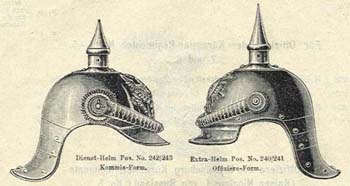

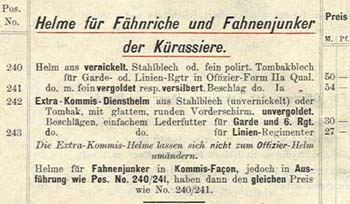

Collectors have struggled for quite some time with the upgrading of the steel Kürassier helmets. Only in the last several years has there been an understanding of one year volunteer (OYV), Fähnrich and Fahnenjunker for leather helmets. Metal helmets catch everyone’s imagination, and because officer or steel helmets are so very expensive, few collectors have experience with these. The emergence of the Neumann catalog has improved our understanding of some nagging Kürassier problems.

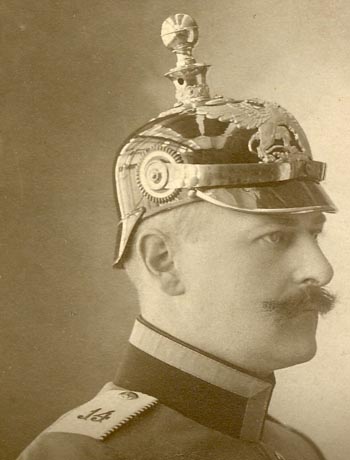

This photograph from the Trawnik collection shows a Saxon one year volunteer with a number of interesting items on the helmet. First look at the front visor. The one on the picture is known as a step visor. The cockade has no silver ring and it is obviously a 65 mm cockade for someone who does not yet have a portapee. The rosettes are round, not trefoil. The spike base has a round ventilating hole and not the design of the officer’s helmet. The spike is round not fluted. We know that a one year volunteer had to privately buy the helmet so this was not issued. Can/would this helmet be easily converted to officer rank?

Let’s take a look at the visors.

The one on the left is the model 1889. It is known as Kommis-Form. It has a round front visor and the spike is a bit shorter. The one on the right is a model 1867, is known as officer-form, has a step visor, a slightly taller spike, and the back is more straight or vertical. Much discussion in the past has centered on why an 1867 model helmet, would be used after 1889 for lower ranked individuals who had not earned a portapee. Conversely, there was not a lot of photographic evidence about those with a portapee but not a commission. A lot of discussion centered on the wear out date. Surely the older helmet styles would not be discarded, and both styles would serve for quite some time in a unit as the wear out date of a steel helmet must be much longer than the 10 years of the leather helmet. However, the helmet form on the right could be bought up through the Junkers catalog in the 1930s.

Analysis has shown that there were four types of helmets. The last three types were all private purchase helmets. Individuals had to buy them from some sort of retailer. Anyone could do it, including the lowest ranked soldier.

1. Issue helmets, also called Kammer quality. These steel helmets can perhaps best be identified by finding a unit mark stamped in one of various locations around the helmet.

2. Diensthelm. Also roughed steel helmets used by individuals who had to individually purchase a helmet, such as a one year volunteer or a Fahnenjunker. They were rough, identical in many ways to an issue helmet and designed to be used for every day and field duty. These are also called Eigentums helm, extra helm, or extra-Kommis helm

3. A helmet for Fähnrich or Fahnenjunker. This would be a high quality helmet with some, but not the entire galaxy of officer upgrades. The intent was to upgrade this helm to full officer when the individual was promoted to lieutenant.

4. Officer quality helmet. Used by a fully commissioned officers from the rank of lieutenant through Colonel.

Issue helmets were the property of the state. The Reichstag voted the money to buy them., the Reichstag voted the money to replace them.. It was not the intent of the unit or the state for individuals to upgrade an issue helmet. Repairs made to the issue helmet were made by the Bekleidings Instandsetung, a Corps level organization designed to fix equipment. Issue helmets were consistently complained about by the wearer as being heavy, poorly ventilated, and chafing to the skull. Felt pads were placed in the top of many steel helmets to stop them from rubbing the top of the individuals head.

The Diensthelm was something needed by those who could not get an issue helmet and were clearly not officers. A one year volunteer needed a Diensthelm for everyday duties, because the OYV was a low ranking enlisted individual. Some OYV types could be commissioned as a reserve lieutenant after two training periods in the reserve. That is after his year of active duty. Many leather Diensthelms were converted to reserve officer status directly. A few minor changes, add a landwehr cross to the wappen and pop-you had an officer’s helmet. Not all Diensthelms were converted, and clearly it was in the interest of the owner to have as high a quality helmet as he could, if he was going to try to convert it. There were so many changes in the Kürassier helm to make a Diensthelm an officer helmet, that it was generally not allowed.

In this catalog there is a clear statement that saying Diensthelm cannot be modified to an officer helm. . It shows the Diensthelm was made out of steel that was not covered in nickel. Chin scales, wappen and other fixtures that were not mercury fire gilded.. It was possible to buy a Diensthelm in either Kommis- form or officer-form.

The helmet for Fähnrich and Fahnenjunker’s was a higher quality helmet that had a nickel finish or a fine polish for the tombak.. You could upgrade the Quality of gilding or silver. These were only available in officer-form and the liners were significantly different and better than the old leather ones. These were fully convertible and upgradable to full officer status. As shown below, the upgrade was dependent upon the original condition of the helmet. Prices were offered in different ranges for instance from 24-27 marks. You could either pay to have it changed over or you could pay much more and have it renovated and changed over. Cockades, rosettes, spike and base, might all be replaced. While this would be a major upgrade it does not seem to be too difficult to accomplish. In the matter of cockades it does not appear as if there was an Unteroffiziere ohne portapee specific cockade for metal helmets. It appears as though it either had a silver ring denoting portapee or it did not. Cockades for these helmets were all 65 mm.

In addition to a total renovation, you could also get parts, fixed. You could get your eagle re-silvered, your wappen or chin scales fire gilded, or a liner installed. The commercial market supported the requirements to keep the helmets in top shape. As a comparison a new line Kürassier officer helmet would cost in the low 60 Mark range.

So the main points of this are (Yes I know this is based on only one catalog):

1. There were four kinds of Kürassier helmets.

2. Diensthelms in Kommis-form could not be converted to officer-form

3. Diensthelms in officer form were not converted (Probably because of the lack of nickel in the shell.)

4. There were three different kinds of. Private purchase helmets that was quite different.

5. Step visored helmets could be bought at any time.

Spiked Helmet Maker Marks

Joeseph P. Robinson

| This concept came out of a list in the old Kaiserzeit Magazine. This current attempt has both pictures and more volume than the old listing. However, it is a work in progress. There is no telling how many errors are in here, duplications or missing parts. There may be quite a few extra makers that are not listed. However we have to start somewhere. So here is a start. Please send your pictures and makers information in and I will post them. This is a common reference. We all will gain from it. The list of contributors is at the bottom. If I forgot to add you it is my fault. Please let me know and I’ll put your name on the list. These are being faked. Especially those stickers. | |

| Aden – Hannover |  |

| Awes Marke (A. Werner & Sohne) –Berlin

Also found on spikes and buttons on rear spines.

|

|

| Babbenfold & Co. — Barmen– B.A.X. | |

| J. Bambus & Co.

Rolled and sewed Filz |

|

| Hugo Baruch & Cie –Berlin |  |

| May Basch in Luchenwalde —Filz Helmets | |

| W. Becker & Co.– Elberfeld |

|

| ?. Becker & Co. Berlin |  |

| Max Brückner

Globus Bavarian Inf brass. |

|

| Carl Billep –Spandau |  |

| Metallwaren Fabrik Gebrüder Bing –Nürenburg — Metal Helmets |  |

| Heinrich Bohlen und Sohn |  |

| Lederfabrik BONAMES Jacob D. Mayer & Co. |

|

| Firma Ludwig Bortfelt –Bremen (cork) |  |

| A. Burgmaier –Munchen |  |

| Hermann Clemen- -Elberfeld

These are stamped on the underside of the front visor trim. |

|

| Franz Cobau –Berlin

|

|

| Vorm. A. Cohn — Guben |  |

| Emile de la Croix –Berlin. |  |

| Alexander Dahl Helmfabrik –Barmen, Ritterhausen |

|

| Damaschke

|

|

| Depaheg Pattent — Fibre helmets

J.B.Dotti This mark is off of a pristine M1857/60.

|

|

| F. & A. Diringer-MÜNCHEN |  |

| M & G DOMPBRTZ???? –Crefeld

On an ersatz oilskin shako

|

|

| D.O.V. (Deutscher Offiziersverein)

|

|

| ?Drong????

Provided by Louis Mayer |

|

| J.M. Eckart — Ulm am Donau |  |

| Ludwig Ess-Ingolstadt

|

|

| L. Estelmann—Strassburg

|

|

| L. Ettinger –Posen |  |

| Herm. Flohr –Cöln |  |

| öFrster & Co. — Filz Helmets | |

| Gammersbach — Rolsdorf |  |

| W. Gemmlich – Berlin |  |

| Firma Goldschmidt –Luchenwalde — Filz Helmets

Name on support disk |

|

| O. F. Günzrodt –Regensburg |  |

| Emil Hagen |  |

| Hast & Untoff

Dresden |

|

|

Berlin-Gubener Hutfabrik Stamm.H.Guben

|

|

| Helbing u. Sackewitz |  |

| Wilhelm Hern –Freiburg |  |

| Firma von der Heyden –Berlin —( kit helmets) |

|

| Adolph Hoffmann –Berlin

A.PB. Hoffmann–Berlin |

|

| Hohmann & Söhne — Kaiserslautern |  |

| Franz Horg(e)(t) | |

| Inclande (—-st) –Freiburg | |

| Gebr Israel |  |

| Wilh. Jaeger |  |

| Julius Jansen –Strassburg |

|

| C. E. Junker |  |

| G. Kaernbach — Braunschweig |  |

| Zerbe & Kaufman — Mannheim |  |

| Kern, Kläger & Cie — Neu Ulm | |

| —-Kleinheinz –München |  |

| A Klucke |  |

| KRUMMELBEIN & CO GMBH LUCKENWALDE LIEFERUNG 1915 |  |

| Lachmann –Berlin |  |

| Seb. Leberfing — Munich |  |

| Karl Leburg –Straussburg |

|

| Firma Lembert–Augsburg | |

| J.G. Lieb & Söhne — Biberach |

|

| Berthold Lissner –Guben |  |

| S. Lubung Strassburg im Elsass | |

| Verkaufskontor Luckenwalder Hutfabriken |  |

| Ludwig & Co. — Frankfurt |

|

| Maller & Co. | |

| Marke Guarde du Corps |  |

| Mars-Orient |  |

| Maury & Co

Offenbach am Main & Mainz |

|

| Martin Mayer –Mainz |  |

| Mohr & Speyer –Berlin | |

| Mühlenfeld & Co –Barmen |  |

| _Müller–Chemnitz |  |

| H. Muller & Co. –Offenbach a. Main & Stuttgart |

|

| Mathias Müller –Liepzig |

|

| Müller & Sarung — Dresden |  |

| Otto Nachtigall –Berlin |  |

| M.A. Neumann –Konigl. Hoflieferant –Berlin W. |

\ |

| J. G. Nieb Sohme– Biberach |  |

| Karl Negele | |

| A. Nolden |  |

| Oekonomie Kunstinstitut –Berlin |

|

| G. H. Osang –Dresden

These are stamped on the underside of the front visor trim. These are also found in the roof of the helmet near the spike on later Saxon metal models. |

|

| Prima Qualitat |  |

| Rabat & Guttmann — Breslau |  |

| Gustav Reinhardt–Berlin

|

|

| Mitteldeutsche Gerberei & Riemenfabrik– Neu Isenburg

|

|

| L. Ritgen –Karlsruhe iB (im Breisgau)

|

|

|

Gustav Röhricht- Berlin

|

|

| Hans Römer –Neu Ulm |  |

| Rumler — Breslau |  |

| Eduard Sachs –Berlin | |

| M. Schambeck– Konigl. Bayer. Hoflieferant | |

| J. M. Schart (?) — Ulm A. B. |  |

| Fr. Schlemmer –Kaiserslautern |  |

| Schletcher Compagne | |

| A. Schmidt –Leipzig

|

|

| L. Schmidt-Rauch–Darmstadt |  |

| Carl Schneider –Brieg |  |

| Firma Schulhof –Berlin — Filz Helmets | |

| Ed. Schultze –Potsdam |  |

| Schulz & Holdefleiss –Berlin N. |  |

| Martin Schumacker –Stuttgart |  |

| Schwarzenberger & Co. –Nurnburg |  |

| Schweitzer–Munich |  |

| Ernst Siegemund –Dresden |  |

| Siemens-Martin-Stahlblech — Metal Helms | |

| C. A. Stahle–Stutgart |  |

| Moritz Stecher– Freiburg-sa |

|

| Instandsetzung Stecher — Freiburg

Possibly the repair facility of the maker listed directly above. |

|

| Johannes Steinberg– Berlin

East Africa Sun Helmet. |

|

| —- Steinmetz –Breslau |

|

| L. STROHMEYER & Co- KONSTANZ |  |

| Bruno Sturm –Guben | |

| Suum Cuique |

|

| Vereingte Textilwerke GMbh –Berlin W9 Vodstrade | |

| Carl Trenner –Berlin Tempelhoff |  |

| Actien Gesh. Thiele — Dresden |

|

| F.H. Thieme –Magdeburg |

|

| Robert Upleger– Danzig |

|

| Hast & Uhthoff — Dresden |  |

| L. Verch — Charlotenburg

|

|

| Wilhelm Voigt –Magdeburg | |

| Herm. Weissenburger & Cie. –Canstatt |

|

| GmbH Wetzlar |  |

| Rudolf Wiener |  |

| C. G. Wilke –Guben |  |

| Rudolf Wismar–Elberfeld |  |

| C. Henke Witterr |  |

| A. Wunderlich –Berlin

|

|

| A Zinna –München | |

| M. Zoltsch — München |  |

| Unsolved Examples | These are marks that have been found but are not readable. Any help is appreciated! |

| The first two words are Deutsche Helmfabrik

then??????? |

|

| Prussian M95 OR |  |

| Schwaben?????? |  |

| Prussian M95 OR |  |

| Prussian M15 OR |  |

| Prussian M15 OR |  |

|

|

| Contributors include:a person who prefers not to be named, whom we shall call Mr. X., Amy Bellars, Mike Huxley, Randy Trawnik, Ron Levin, Max Chaffotte, Tony Schnurr,Chip Minx, Michael Hyman, James LeBrasseur, Reservist1, Charles Booth, Brian Loree, Danny Watson, several annonymous ebay donators who gave permission, Gus Bryngelson, Rebecca Copple, Dave Carlson, Dave Mosher, Mick Edwards, Tony Cowan, David Zeller, Mark Avery, Mike Freiheit, John Mordini, Mike Prictor, Scotties Guns and Militaria, Tim Quinlan, Tammy Venne, Kieth Gill, Stu Williamson, Belginator, Robin Lumsden, Geri Neumann, Steve Russell, Karl O. Salvini,Martin Vear, Denton Walter, Karel Van Bosstraeten, Roy A., Daniel Leroy, Andy Archer, Chuck Liles, Philippe Quesnay, Robert Hinsley, Denton Walker, Bob Jones,Jeroen Meijer,Ronny J. Kastoun, Chris Hanson, David Milo, M. Buchner, Laurent Mirouze, John Mann, | |

Latin American Pickelhauben

Any additional information about this matter, will be duly appreciated.

My email is :

ricardojarafranco at gmail.com

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VfBnQWD9IIQ

Ricardo Jara Franco

August 18, 2011

|

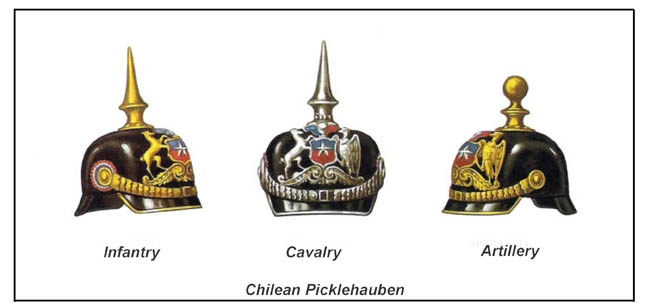

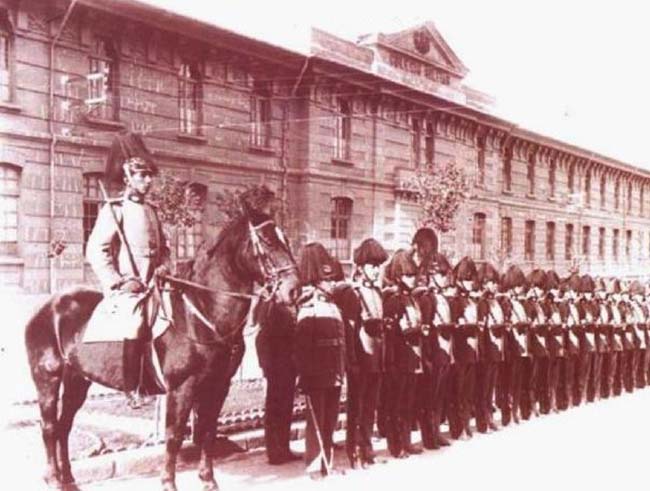

CHILEAN SPIKE HELMETS Chile is probably the last country in the world to dress and parade in the old Prussian-style. The Regulation of Uniforms of 1898, and the Ordnance from February 06, 1905, put an end to almost two centuries of French influence in the Chilean uniforms and military instruction system. The Chilean Army now appears in all the splendor of Spiked helmets and under the influence of old Prussia. This influence remained stronger in the Chilean Armed Forces, but especially in the Army, compared those of other Latin American countries. Also, Chile has exercised a strong formative influence on the Armed Forces of others countries in the area : The Armed Forces of Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela, Honduras and El Salvador have come under the tutelage of Chilean military missions, in some cases for very long periods, and others countries have sent military personnel for post-graduate training in the Military Schools, and for experience with units of the Chilean Army. The Prussian ceremonial uniform is not a contradiction to the NATO standard that Chile pursues for their Armed Forces nowadays.

The Director of the Military Academy (Colonel), his Staff and the Flag-bearer with gorget. How strangeit is to see an officer dressing as the ” I. Garde-Dragonen-Regiment Königin Victoria von Grosbritannien und Irland” or cadets dressing in the uniforms of the “Grenadier-Regiment König Friedrich Wilhelm II Nr.10” , in 2011! Picture: Hutzcruffe. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l26FSmsISnw The first pickelhaubes appeared in 1900, in the “General Bernardo O’Higgins” Military Academy, School of NCO of the Army (Escuela de Clases), War Academy, and in the Squadron of Cavalry of the Presidential Guard, in the parade formations and in guard’s service. However, in 1879, the “Chacabuco” battalion used a lot of pickelhaubes that were originally Peruvians but captured by the Chileans, in the war of 1879-84 against Peru-Bolivia (Pacific War). However, these helmets didn’t participate in battle being relegated to police activities. These helmets amazingly still carried the German Imperial eagle, and were model M/1867.

“Chacabuco” Civic Battalion (stationed in San Bernardo, 1879), carrying Prussians helmets confiscated from the Peruvian State during the Pacific War ( 1879-1884 ) – with their original Prussian badge. Picture : Coll. Gen. Roberto Arancibia Clavel.

Engineer Domingo De Toro Herrera, Commandant of the 6th Line Infantry Regiment ”Chacabuco” next to a soldier wearing a pickelhaube captured from Peru, 1879.

After 1899, Germany and Austria manufactured Spiked helmets dedicated to Chile regularly. The shape and model were similar to those of the Kaiser Army (pattern 1891 and 1895),used by the Prussian Garde Regiments.

Pickelhaube used by the Army (Enlisted Men’s Helmet), with this first helmet plate, and then dedicated exclusively to the Military Academy. Coll. Jean-Manuel Torti.

Above left: Uniform of a Major from the Chilean Army, with square visor helmet and the helmet plate, prior to 1905. Right: Cavalry Captain, from the Military Academy- round visor, with a helmet plate, post-1905 (with silver metal).Coll. Raúl Yáñez M.

First lieutenant Vicente Villalobos, picture taken at the Cavalry-School in Hannover, Germany, 1903. The Imperial eagle plate was replaced by a very similar one specifically made for Chile. Starting in 1905, the national coat of arms was made in Germany, and later on in Chile. This emblem was adopted in 1824, and changed with their motto in 1854 by the Army; it represents the Chilean national emblem: a huemul – Hippocamelus bisulcus – (small fawn, today in danger of extinction), and a condor, contouring a bicolor shield with the slogan: “Through reason or Forcer”, in Latin: “aut consiliis aut ense”. During certain periods this motto was replaced by the sentence “Republic of Chile “. From the 1970´s on, the front plate uses the original motto, which is the official slogan of the state of Chile since 1920.

Army square visors Spike helmets. The artillery helmet has the cockade on the right side only, the Infantry and Cavalry helmets possess both. These models definitively disappeared, in between 1924 to 1927.

Army’s square visor Helmet, with white horsehair parade plume (1905 to 1927).

Left: Cavalry helmet (Enlisted Men’s Helmet), used up to 1924-27, with silver metal: The other branches used brass metals. Right: Prussian Spike Helmet and Chilean Infantry Helmet, same period, NCO model (used chinscales, with M/1891 side post).

Chilean Captains Arturo Ahumada B. ( Artillery ) and Diego Guillén Santana ( Infantry ), reformers of the Colombian Military Academy, 1907-1909.

The same Officer of the previous picture, General Arturo Ahumada Bascuñan (1872-1955). See the officer’s medals, obtained in Germany between 1914-1917.

Left: “Through Reason or Force” Right: “Republic of Chile “. The Military Academy adopted a brass eagle with imperial crown as its emblem (First Model)!! An imperial eagle is rare to see and a very sought after item for collectors and museums alike. There is a white metal foil that simulates the feathered neck of a condor, with its deployed wings that has in its claws a grenade and a sword. On it’s chest is a silver star, and the slogan “Through Reason or Force “.This exclusive model of the Military Academy was in use from 1900 to 1927. The helmet was replaced in 1927 after the railroad tragedy of Alpatacal. During a trip to Argentina the helmets and their emblems were almost totally lost in a fire that also took the life of twelve people, including the Director of the Academy. The helmet was replaced by similar helmets to those that had been used by the rest of the army since 1905 with the Chilean coat of arms on the front. The only difference was the round visor used exclusively by the Military Academy, while the rest of the Army used a square visor.

The first helmet emblem used by the Army up to 1905 and by the Military Academy up until 1927 (Officer’s Helmet M/1891) . Coll. Raúl Yáñez M. Infantry Major of the 1st Infantry Regiment “Buin”, prior to 1905.Coll. Raúl Yáñez M.

General´s helmet, post-1905, with parade feather plume.

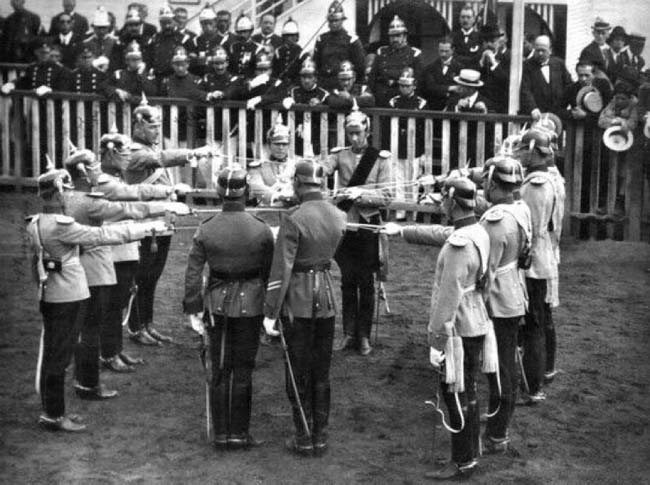

“General Bernardo O’Higgins”, Military Academy on parade. Picture taken in December 23, 1915.

Student of the Non-Commissioned Officer School (Escuela de Clases), 1906.

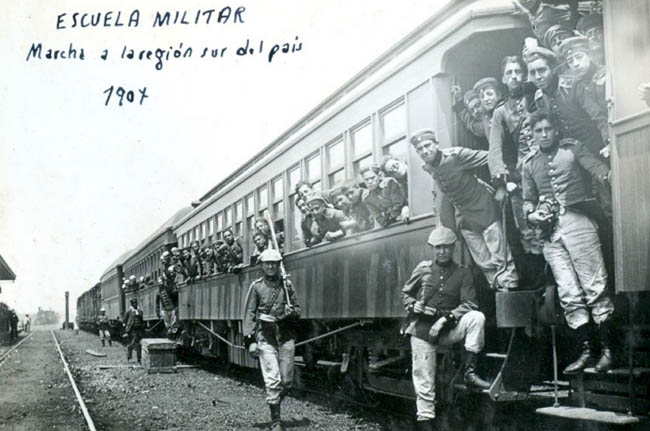

Military Academy departing for Summer’s maneuvers, 1907.

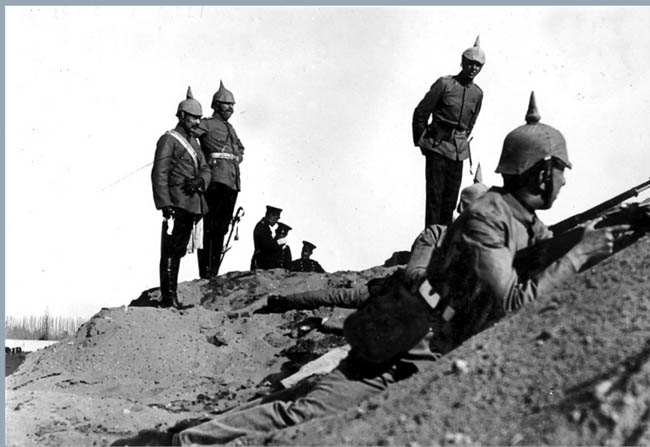

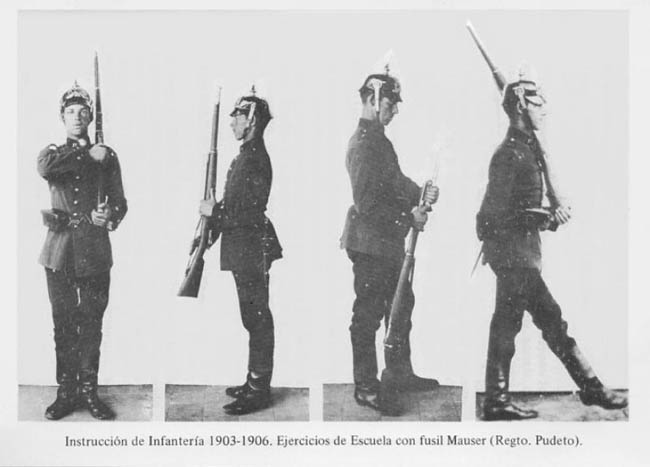

Cadets participating in infantry maneuvers, September 07, 1909. Infantry instruction with Mauser rifle ( ”Pudeto” Regiment, 1903-1906) Picture: Coll. Lt. Col. Edmundo González S.

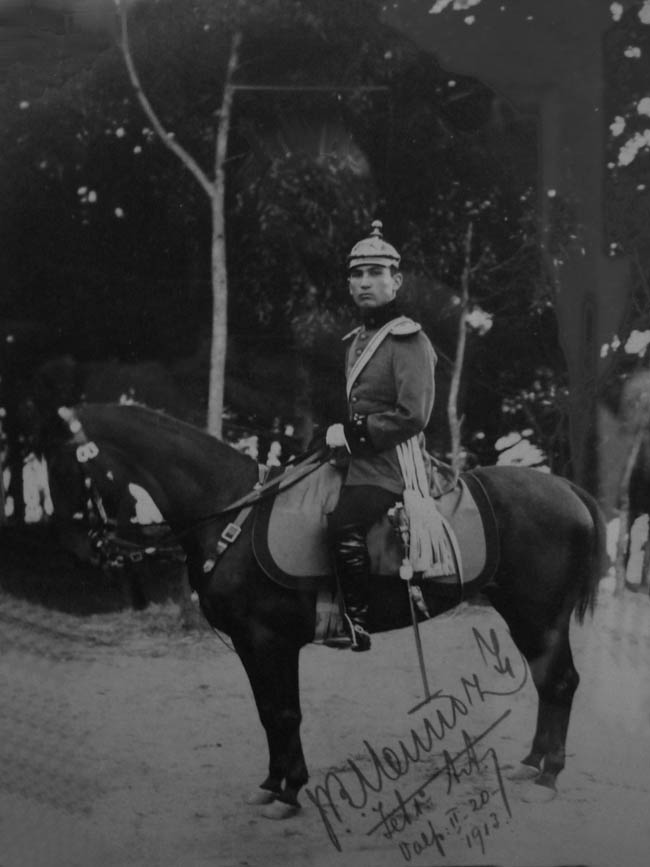

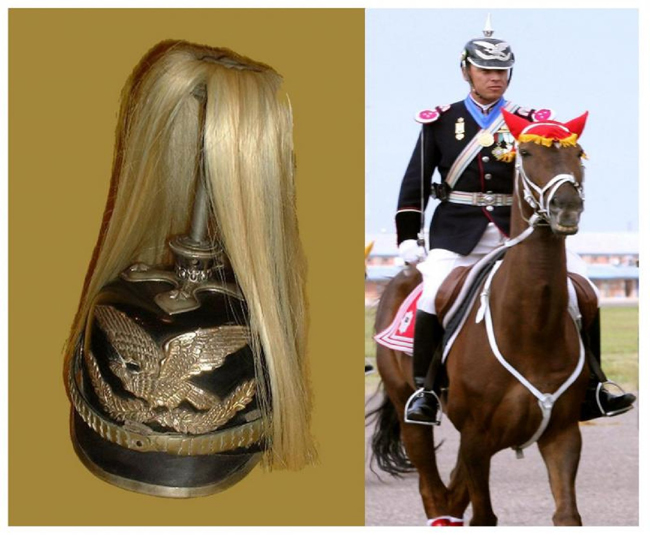

Artillery Lieutenant in parade uniform, picture taken in February 20, 1917. Valparaiso. Coll. Raúl Yáñez M. Chilean Cuirassier Helmet

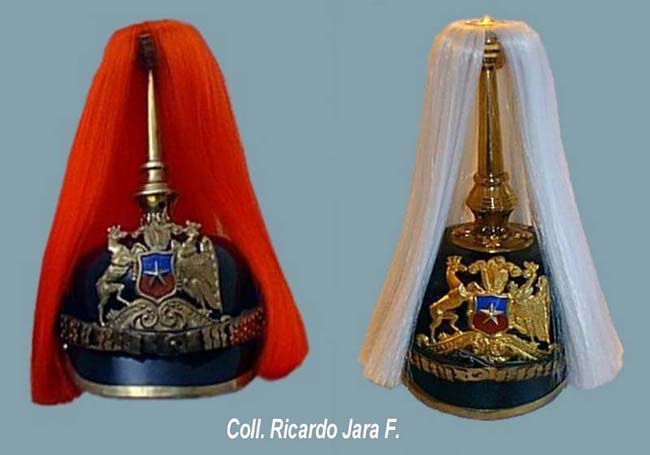

Chilean Condor for Cuirassier helmet: Brass color for the Cavalry School (with spike), and silver for the Presidential Escort (with wing-spreaded condor on top).

Beautiful and rare Cuirassier type helmet, used by the Chilean Army (Cavalry School). These were only used for big State ceremonies between1900 to 1930. This helmet, belongs to John Mordini ´s collection.

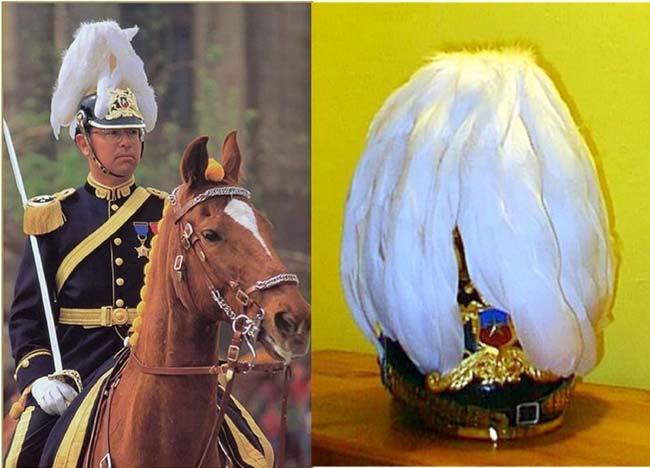

Cavalryman of the Cavalry School, in orderly uniform. The picture taken Circa 1912, clearly shows the Cuirassier helmet M/1889-94. In front: Private from the “Carabineros” Regiment (belonging to the Army), around 1920, which in 1927 became the National Police nucleus. Picture: Carabineros de Chile Museum. Behind: Cavalry Squadron (from the Cavalry Regiment Nr.4 “Escolta”) , on duty as Presidential escort, in front of”La Moneda” (Presidential Palace).

Officer and Non-Commissioned Officers (NCO) from the” Carabineros” Regiment, Guards of “La Moneda” Presidential Palace (House of Government), Ca. 1918.

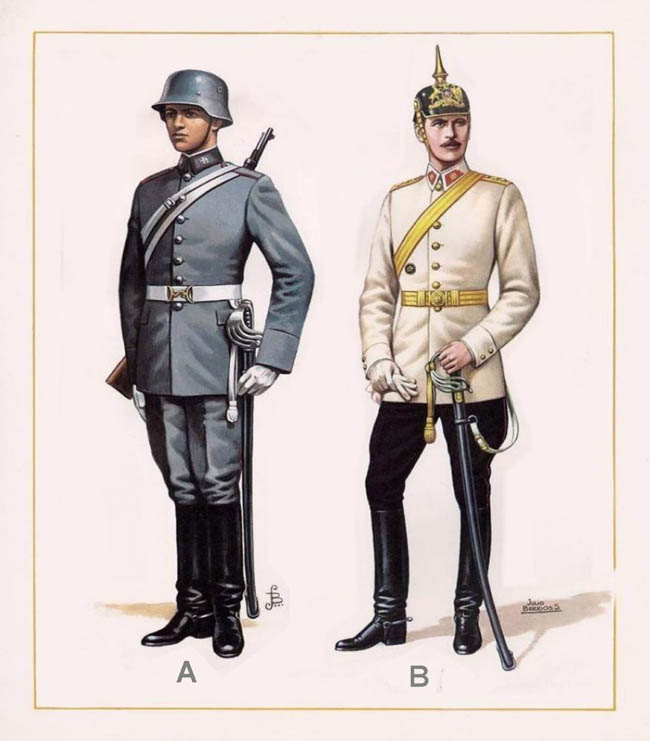

From 1940 up today, this Cavalry Squadron (Presidential Escort) maintains the old uniform of the Regulation of 1940 (O.C. N° 89, April 11, 1940). For troops as in Figure A, carrying a model M/1891-96 Chátellereault J.H. (M.A.C.) saber, and for Officers (from 1984 to 1998) ,as in Figure B, with Prussian helmet (Note the presidential badge to the right side, at the height of the fifth button ).

The Chilean Army, discontinued the use of the spiked helmet in August of 1924.The last official use was for the parade that was organized in honor of Prince Humberto of Saboya, in the actual O’Higgins Park (early Marte field), nevertheless the helmet was used for a few years more, circa 1927, in the provinces.

Left: Model used by the Military School, from 1927. In this case, uses the “long spike” and the round visor. Right: present model, made of leather, with artificial hair and cone spike.

In 2006, the Austrian company responsible for providing leather helmets to the Military Academy ceased production. Chile then began to buy in Eastern Europe to fill the needs of the army, but now all the parts and brass pieces are locally produced.

Left: nspiked helmet of the Parade Band. Right: Spiked helmet used by Cadets and Officer. Both hairbush are made of horsehair. An experimental fiber spike helmet was tested during the 90´s. It was not accepted as it did not match the leather helmet in ventilation and weight. But probably this rejection was more heavily based on tradition and historical background. Ecuador, Venezuela, Bolivia (Anapol) and Colombia use fiber helmets.

Experimental fiber pickelhaube.

Left: Liner of an experimental fiber helmet. Right: Liner of an actual leather helmet.

The same hairbush as the previous ones, but with artificial hair (1960).

Left: Detail of the hairbush mount and round base. Right: Details of spikes used in the helmets of the Military Academy. Spike of “Cone” ( 84 mm. ), “Short” Spike ( 82 mm. ) ,” Long” Spike ( 91 mm ), and Cavalry Spike ( NCO, 73-90 mm ) . The Cone Spike is used at the present time .During the use of the Spike helmet by the Army (1900-1924), the troops used a short spike, and the Officers a long one. RED HAIRBUSH Corps of Drums and Fifes of the Military Academy (formed by Cadets), 1907. To the left, Major Günther von Below, German instructor.

Fanfare section of the Military Academy Band, 1949. Picture: Magno Lazcano C.

Corps of Drums, Fifes and Bugles of the Military Academy with Prussian swallow’s nests and Academy Schellenbaum (or “Jingling Johnnie “), 2007. With a Drum Major : http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1mU7gL_m20I&feature=related With a Bugle Major : http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=idKT3bycxS8&feature=feedf Military band during parade practice : http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=In0Kj-ARaZA&feature=feedf http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jUwhmacL8R0&feature=feedf

OATH OF ALLEGIANCE TO THE COLORS

Oath of allegiance to the colors, Officers of the 8th Cavalry Regiment “Exploradores”, Antofagasta, 1921.

Military cadets make their oath of allegiance to the colors. 2007 DETAIL

Director of Military Academy (Colonel) with his special Spike helmet, with parade feather plume. This helmet is exclusive to the Director, thus it is very desirable and scarce, for collectors.

Chin scales detail (brass scales, 16-17 or 18) and cockade with ring, locally produced.

National Coat of Arms.

Parade funnel detail, and shoulder boards of Officer ((2nd lieutenant). Picture: Juan P. Catepillán Flag-bearer of the Military Academy. CARABINEROS DE CHILE ( CHILE´S NATIONAL POLICE FORCE )

Second lieutenant of Carabineros de Chile Humberto Reyes Rojas, 1929, picture taken in Tacna, Peru. Picture: “El Mercurio” journal. Right: Officer Spike helmet from Carabineros de Chile, National Police since 1927.Carabineros de Chile Museum.

Carabineros Helmets, from 1908 to 1930. Picture: Carabineros de Chile Museum.

Captain Larrain. Guard of Presidential Palace (Carabineros, 1920), with a beautiful pickelhaube with a condor of deployed wings. MEMORIES

Left: Artillery Major in Parade uniform, with artillery ball, 1905. Right: Officer of the 3rd Artillery Regiment “Chorrillos”, ca. 1910.

Left: General in parade uniform, 1905. Right General Sofanor Parra Hermosilla, with parade feather plume. Picture taken circa 1912. Illustration: Cavalry Lieutenant and Regimental Adjutant, in parade uniform 1905, with the adjutant’s belt worn over the shoulder. Picture: Cavalry Captain from the Military Academy, with M/1891-96 Chátellereault saber Coll. Raúl Yáñez M.

Left: Engineer Colonel, 1905. Right: Engineer Second lieutenant. Picture taken circa 1915.

Left: Infantry Lieutenant, in Parade uniform, 1905. Right: Infantry Lieutenant Julio Franzini (in Ecuador from 1901 up to 1906), with the First model helmet plate, 1904. Left: Cadet, Military Academy, 1920. Right: Cadet, 1920. ARGENTINEAN SPIKE HELMETS 1910 – 1924

Cruciform spike base and fluted spike for Argentinean General’s helmets. Illustration: ”Reglamento de Uniformes Militares de Argentina, de 1912”

Cadet Juan Domingo Perón, 1911.

Infantryman of the 3rd Infantry Regiment, wearing his Model 1910 pickelhaube (with leather chinstrap).Coll. Raúl Yáñez M. Uniforms of French influence with German pickelhauben. From : “Evolución de los Uniformes Militares Argentinos” by Major (Argentinean army) Sergio O. H. Toyos

Cavalry Officer’s helmet with round base and plain spike, 1910-1924. Coll. Wilson History and Research Center.

Argentinean Non-Commissioned officers ( NCO) Spiked Helmet, 1910

Left: Corporal of the 2nd Line Artillery Regiment, 1911. Illustration: Eleodoro Marenco, 1966. Right: Officer of the 1st Line Artillery Regiment, 1912. Coll. Raúl Yáñez M. BOLIVIAN PICKELHAUBE

Bolivian Police Academy (Anapol) , with avocado hairbush.

Bolivian Police Academy: “Academia Nacional de Policia “(Anapol). Officers and troops, on parade formation.

Bolivian soldier, Ca. 1930. |

Officers and troopers, on Presidential Escort. 2010. Foto: Venemil.

Helmet of the Bolivian Military Academy “Colonel Gualberto Villaroell“. Made by WKC ( Weyersberg, Kirschbaum & Cie., Solingen, Germany )

Bolivian Military Academy. Ca. 1950

Bolivian Military Academy “Colonel Gualberto Villaroel“.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A2Lf_L_h9HY&feature=related

High School marching bands

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3SR5BCczTtI&feature=feedf_more

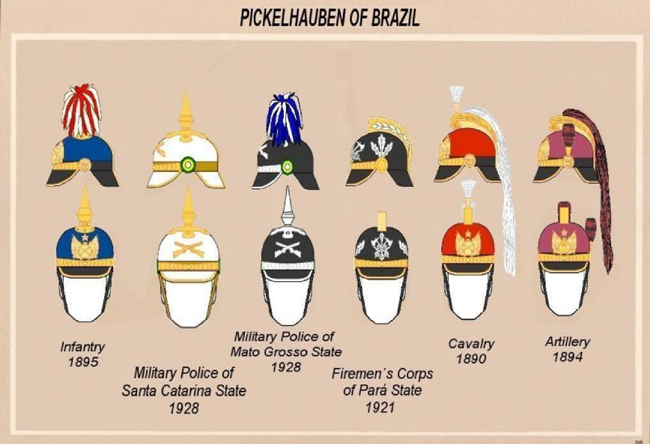

BRAZILIAN PICKELHAUBE

1889 – 1928

Their use began in 1889, with some distinctive modifications in 1890 and 1894. The Brazilian helmets show a Portuguese heritage with the style of the front badge, accessories and decorations; their uniforms, are a very interesting blend of French, British and German military fashion. 1903 was the final year for the Brazilian Army spike helmets. They were in use with Police Corps and Firemen until the year 1928.

Old helmet plate of the Military Police of Paraná, “Regimento de Segurança”, 1913

Assorted models used by Brazil. Wikipedia (Guilman).

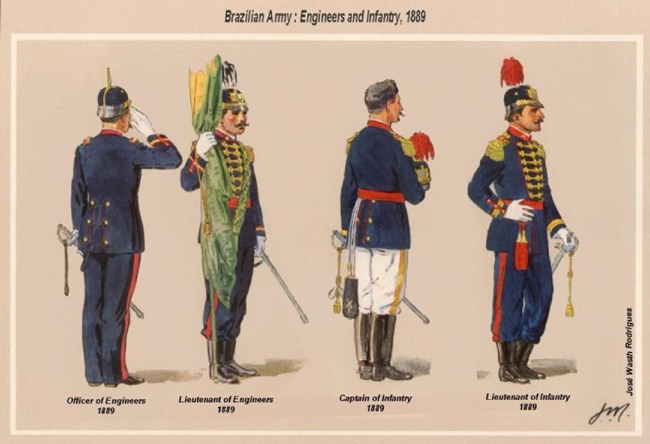

Officers of the Brazilian Army, between 1889 and 1890. Illustration: José Wasth Rodrigues.

Officers of the Brazilian Army, 1889. Illustration: José Wasth Rodrigues.

Pickelhaube of Military Police of Paraná State, Brazil, 1913-1917. Picture : Wikipedia ( Portuguese )

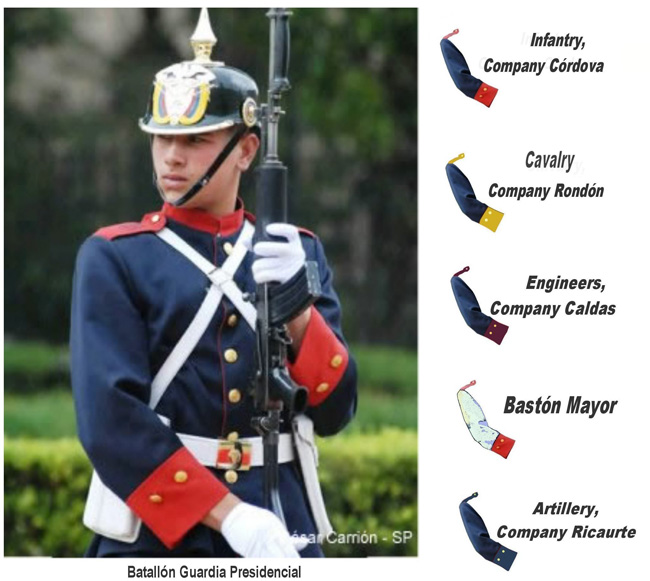

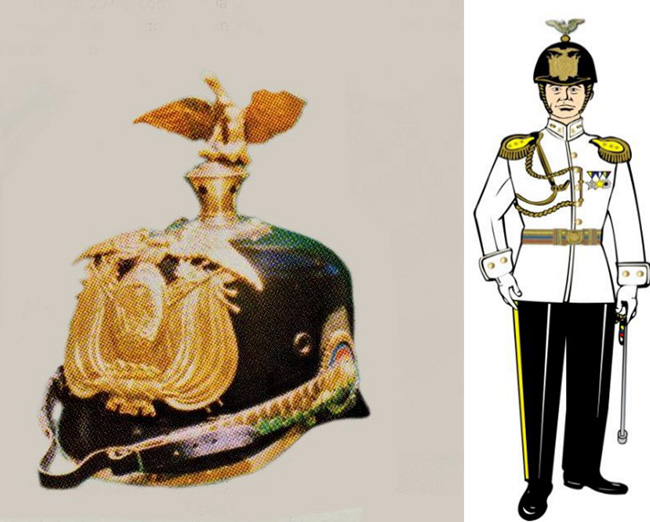

COLOMBIAN SPIKE HELMETS

1907 – Present-Day

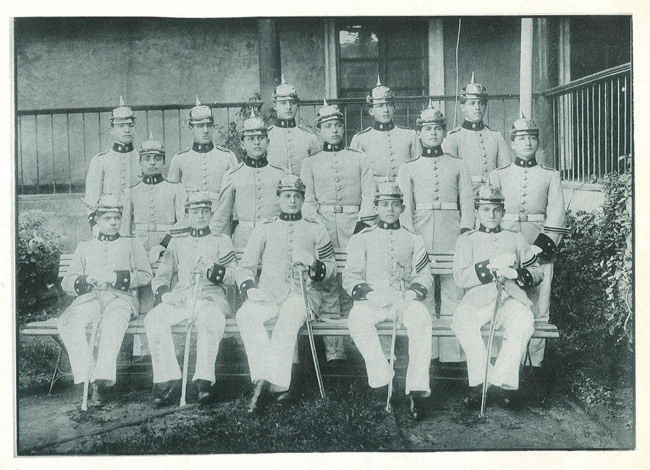

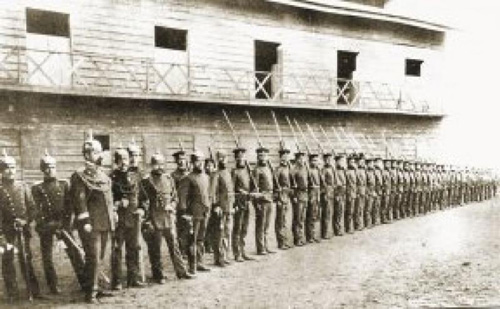

The use of the pickelhaube, begins with the great restructuring of the Colombian Armed Forces of 1907. At that time a Chilean military mission imposed the use of the Prussian spike helmets, that has survived until the present. In Colombia, the spike helmet enhances the presentations and parade of the Military Academy, Guard Battalion of the Presidency (Presidential bodyguard), the Police Cadets School and some High School marching bands.

Military Academy (Escuela Militar de Cadetes) “General José María Córdova“ founded on April 13, 1907 (Decree Law N° 434).

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T4M9Z1ZuUdY

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fBIFQuCuIBI&feature=youtube_gdata_player

Military Academy Band, playing an old Chilean march : “ Adiós al 7° de Línea” ( Good-bye to the 7th of line )

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=69v_EqZTjiA&feature=youtube_gdata_player

The Chilean original version.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dsHVaWxAXUQ&feature=youtube_gdata_player

Cadets belonging to the Colombian Military Academy.

Guard Battalion of the Presidency (“Rondón” Cavalry Company), created on August 16, 1928.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0u1bM3wJADc

Guard Battalion of the Presidency (Infantry Company” Córdova”).

Cadets and Officer of the Police Academy ” General Francisco de Paula Santander”.

Parade in a rural area :

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RYm7ItG3HYk

High School Marching Band, playing an old Chilean march : “ Adiós al 7° de Línea” ( Good-bye to the 7th of line )

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Mf4IESY8vI&feature=feedf

ECUADORIAN SPIKE HELMETS

1907 – Present-Day

A Chilean military mission begun the adoption of the Prussian instruction and uniforms for the Army of Ecuador in 1903. The Regulation of January 10, 1907, made it standard for the Army and the Military Academy. The cadets of the Ecuadorian Military Academy “Eloy Alfaro” has kept this tradition until today. The current helmets are made of fiber and they possess two lateral vents on each side.

Military Academy Cadets from “Eloy Alfaro” Military Academy. Picture taken in 1911.

Cadets carrying the pennant from the “Eloy Alfaro” Military Academy, with yellow hairbush.

Front badge of Ecuadorian Prussian helmets.

Fiber helmet of the Ecuadorian Military Academy. Note the lateral vents.

The“Great Parade” fiber helmets, used by the “Eloy Alfaro” Military Academy Senior Officers. The Staff officer graduates use golden condor helmets (Left), the officers without title (General Staff), use helmets with silver color condor (right). Ecuadorian Army Uniforms Regulation 2007, article 50.

Helmet from Ecuador, this one is different to the above samples and it is similar to the 1848 original model. Sent by Eduardo Espinoza

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vXSZXWuVJh4

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kq8cA6zu_70&feature=youtube_gdata_player

EL SALVADOR SPIKE HELMETS

1901 – 1927

In 1890 a German Military mission was hired by the Salvadorian Army, being reinforced later by a Chilean military mission, which operated in the country from 1903 to 1909 and from 1951 to 1957. The Prussians helmets are a sample of this influence.

Front badge of spike helmets of El Salvador.

M/1895 Prussians helmets, in the “Museo de Historia Militar” of El Salvador. Picture: Mr. Carlos Rodriguez Mata

A group of Cadets from the Military Academy, in front of the “Palacio Nacional”, City of San Salvador, El Salvador, 1924. Picture: Mr. Carlos Rodriguez Mata.

HONDURAN SPIKE HELMETS

1904 – 1912

The Military Academy of the Army of Honduras was organized in August 31, 1904 (Law Decree Nr. 56), by the Chilean Captain Luis Oyarzún, which introduced the use of the pickelhaube among the Officers of the Army.

General Abel Villacorta, 1908. Picture : “Dirección de Historia Militar, de las Fuerzas Armadas de Honduras”

MEXICAN SPIKE HELMETS

1905 – 1910.

The Mexican pickelhauben had a very brief existence. It was born under the Porfirio Diaz Presidency, and the Uniform Regulation of 1905. It was a curious mixture of German, French and British military fashion, and was made obsolete by the Mexican Revolution in 1910. Nevertheless it was only eliminated by the Uniform Regulation of Sept. 1919, and it persisted in some Military Schools until the mid-1920’s (for example, in the Infantry School). It was only employed by Officers of higher grade, the Cadets of the Military Academy, and the Military Schools, that is the reason why the scarce helmets that exist today are of extraordinary quality.

Picture from the Centennial of Mexico. Officer Porfirio Díaz Jr., Mrs. Carmen Romero Rubio and General Porfirio Díaz (in civil attire). Sept.01, 1910. Picture: “Seis Siglos de Historia Gráfica de México 1325-1976”, Gustavo Casasola.

Cadets of the Military Academy, September 16, 1910. Picture: “Seis Siglos de Historia Gráfica de México 1325-1976”, Gustavo Casasola.

Military Academy, September 8, 1910. Picture: Gustavo Casasola, “Seis Siglos de Historia Gráfica de México 1325-1976”.

Cavalry Captain´s helmet, 1910. Coll. Juan Matos, Mexico.

Gen. Gonzalo Acosta Mason helmet (Historical.Ha.com).

Cavalry General helmet, with parade plume, 1910. This helmet was Auctioned on September 07, 2010, by the House Louis C. Morton, in USD$ 11,556.

NICARAGUAN SPIKE HELMETS

1893 -1909.

The German influence was present in the Army from 1893, and it ended in 1909, with the anarchy and the subsequent American intervention in 1912.

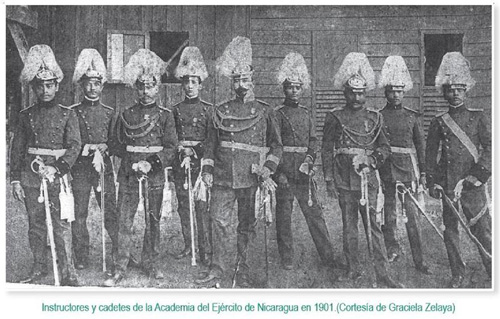

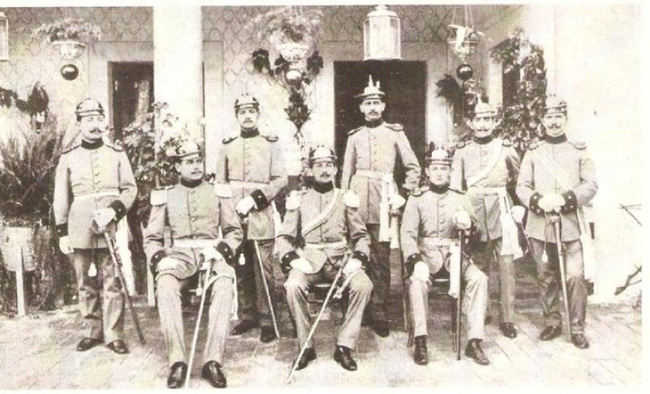

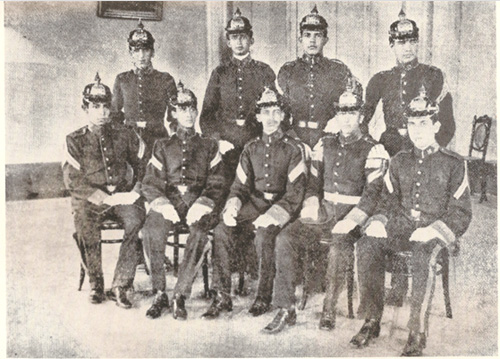

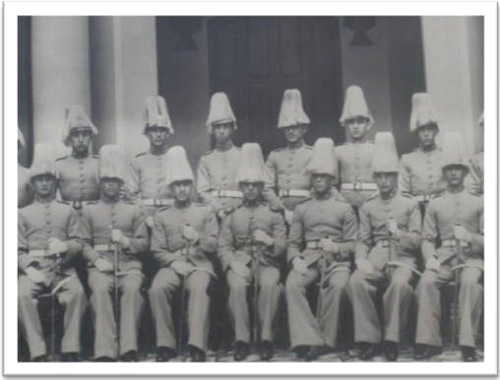

Formation of the Military Polytechnic Academy of Nicaragua, 1901. The tallest Officer in the picture is the Engineer Camilo Castellón, Secretary of War, and the Officer at his right, is the Colonel Kart Uebersesig, German Instructor and Director of this Academy.

Instructors and Cadets of the Military Polytechnic Academy of the Army, (Mr. Castellón to the center, and the colonel Uebersesig to the right),Nicaragua, 1901.

PARAGUAYAN SPIKE HELMETS

1900 – 1930.

Front helmet plate of Paraguay

The Prussian helmet served in the Paraguayan Army since 1900, and with the advent of the French military missions in the late 20s that changed the organization and the equipment of the Army, they definitively disappeared from its inventory.

Paraguayan Officers. Ca. 1928. Coll. Ernesto Sosa.

PERUVIAN SPIKE HELMETS

1872-1880.

They were used from 1872, and until the defeat of the army, in 1880. The army began to use it since the Uniforms Regulation of 1872, in the parade and daily uniforms. It is know to have been used, at least, by 2nd Cavalry Regiment ” Lanceros of Torata”, the 1st Line Infantry Battalion ” Pichincha” , and an Artillery regiment or battalion.

Wonderful picture of an Artillery Lieutenant of junior grade ( Alférez ), in daily uniform, Lima, 1879. The Picture is from the book: “La Guerra de Nuestra Memoria, Crónica Ilustrada de la Guerra del Pacífico”, by Renzo Babilonia Fernández Baca, January 2009, Peru.

Cavalryman of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment. “Lanceros of Torata” (1872) Ilustration: “Evolución Histórica de los Uniformes del Ejército del Perú (1821-1980)”, Peruvian Army, Dic.2005.

URUGUAYAN SPIKE HELMETS

1924 -1932.

Coat-of-Arms of Uruguay

The Country possesses a strong French tradition in its Armed Forces, however between 1924 and 1932, the “Guardia Republicana” (Mounted anti-riot Police), used a type of spike helmet similar to the M/1895 model, with its corresponding hairbush and the national Coat-of-Arms.

Spike helmet of the Republican Guards (Mounted Anti-Riot Police). Coll. Carlosraul187, MercadoLibre Uruguay.

VENEZUELAN SPIKE HELMETS

1918 – 1945 and 1971 till Present-Day

The pickelhaube appeared with the reorganization impelled by the Chilean military mission from 1910 on, that brings to the Army the characteristic view of the Prussian pattern. In 1918, the Military Academy of Venezuela, adopted the spike helmet that remained in use until 1945 (in 1936, it changed from black color to turquoise). However, it reappeared on June 24th, 1981, and on 2007, the National Shield was changed, to the new Bolivarian Coat-of-Arms. Starting in September 2010, different colors of hairbush were adopted for the different levels of the Academy Cadets. The Air Force Academy adopted between 1982 and 1986 a strange model of pickelhaube that had a short period of use.

Cadets of the “Escuela Militar” of Venezuela, 1918. Picture: Foro Militar de Venezuela.

Cadets of the “Escuela Militar” of Venezuela, period 1936-1945. Picture: Foro Militar de Venezuela.

Cadets of the “Academia Militar” – Military Academy- of Venezuela, current – 2nd year academic level -.(Former “Escuela Militar” to 1998)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e7s1D1IjbcM

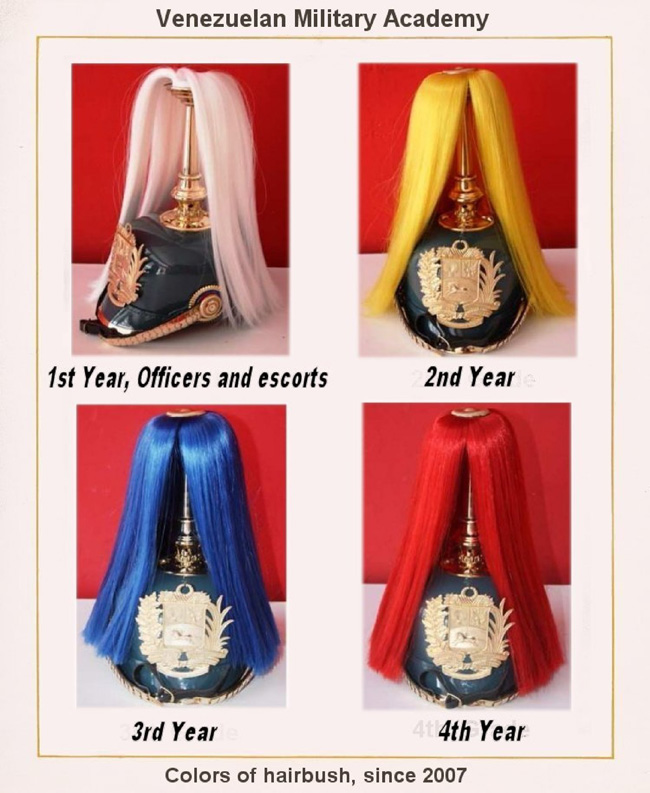

Parade plume colors, for each academic level of the Venezuelan Military Academy ( Since 2007 )

Cadet of the Military Academy, in parade uniform (3rd Year)

Spike helmet from the “Escuela Militar de Venezuela”, prior to 1936. Coll. Raúl Yáñez M.

Helmet Plate from Venezuela, previous to 2007

Current helmet of the Venezuela Military Academy, with the new Bolivarian front badge.Note the horse facing left and compare with the previous badge. The change took place in 2007.

Cadet of the Air Force Academy (FAV), with their peculiar helmet, used from 1982 to 1986.

Bibliography :

1.- “Les Coiffures Prussiennes de l´Armée Chilienne”, Gazette des Uniformes, Nr. 204, Sept. 2002, by Jean – Manuel Torti

2.- “L´Armée Chilianne Prussianisse”, Gazette des Uniformes, Nr. 154, by Juan Angel Torti

3.- “Historia del Ejército de Chile: Nuestros Uniformes”, Tomo XI, 1985, EMGE.

4.- “Cuatro Siglos de Uniformes en Chile”, by Antonio & Alberto Márquez Allison, Library of Congress UC485.C5M37 1976.

5.- Abstract: “La Escuela Militar y el casco Prusiano, Antecedentes Históricos”, by Colonel Alberto Márquez A., Chilean Army

6.- “The Kaiser’s Army in Color, 1890-1910”, C. Woolley

7.- “Memorial del Estado Mayor del Ejército de Chile”, Feb. 1913. Chilean Army magazine

8.- “Retrato: Los Héroes olvidados de la Guerra del Pacífico”, M. Pelayo, C. Arce, E. Gardella, Santiago, 2007.ISBN: 9562845826

9.- “Uniformes de la Guerra del Pacífico: Las Campañas terrestres 1879-1884”, Greve y Fernández. ISBN: 978-1-85818-582-8

10.- Abstract “Información sobre el casco de la Academia Militar de Venezuela (A.M.V.), by Eddie Ramirez

11.-“Seis Siglos de Historia Gráfica de México 1325-1976”. Gustavo Casasola.

12.-“La Guerra de Nuestra Memoria, Crónica Ilustrada de la Guerra del Pacífico”, by Renzo B. Fernández Baca, Peru, January 2009.

13.-Abstract “Evolución de los Uniformes Militares Argentinos” by Major Sergio O. H. Toyos, Argentinean Army.

14.- “Armed Forces of Latin America”, by Adrian J. English/Jane’s Publishing Co., 1984, ISBN 0710603215

15.- “La influencia del Ejército chileno en América Latina 1900-1950”, by Roberto Arancibia Clavel, CESIM, Santiago, 2002. ISSN 0717-7194

16.- “Evolución Histórica de los Uniformes del Ejército del Perú (1821-1980), Peruvian Army, Dic. 2005

Scroll Helmets

Scroll Helmets

Joe Robinson

Several years ago a friend of mine named Martin asked a series of simple questions concerning a filz helmet he had bought that had a scroll Wappen on it. My opinion flipped back and forth and I really do not think I did Martin any great service. However, it started me off on a search for “truth” concerning the scroll helmets. I have yet to figure it all out but thought I would put some thoughts down. My paltry efforts are all due to Martin and I thank him.

There is very little information on these helmets and very few pictures. As one of the benefits of earlier versions of this article more pictures have come out of the woodwork and collections .

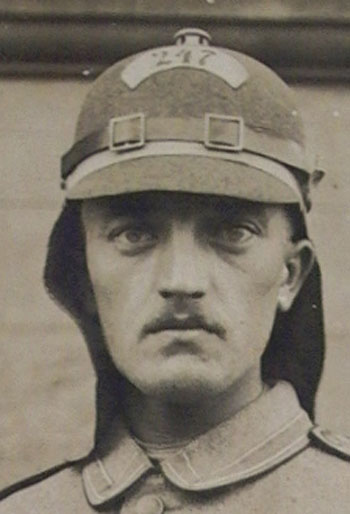

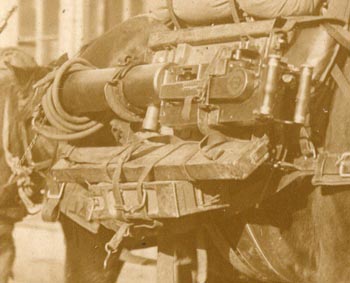

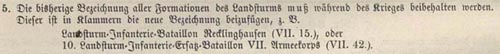

On the eighth of December 1915 the Prussian War Minister authorized the use of an experimental helmet for use with some troops earmarked for Serbia.ii Instead of having an eagle for Prussia as a helmet Wappen these helmets had a metal number shield in its place. The shields are known as scrolls. Thus was born the legend and confusion of the scroll helmets. The Illustrated War News printed a picture of some machine-gun troops with this helmet in 1915.

In the modern conventional wisdom confusion raised its ugly head and the sources for the specific helmets were lacking. So I thought I would start looking at it from the simple approach of what, where when, who and why.

What

Using the generic term of scroll helmet is far too simplistic. There are several items that are consistent. For instance these helmets were almost never worn with the spike. It is not clear if they were ever issued a spike. There were no cockards worn. There seems to be three specific types scroll Wappen.

1. This is the type most commonly seen in pictures. It consists of a metal semicircle of simple shaped scroll with cut out numbers. The method of attachment to the filz helmet cannot be determined from the pictures. We will refer to this as type 1. There is a variant to the type 1 which has a design on the edge and a lip around the outside. We will refer to this as type 1A.

2. This type is commonly seen in surviving artifacts and examples. It consists of a metal plate with embossed numbers. The helmet plate is secured through the use of split brad retainers. We will refer to this as type 2.

3. This type is commonly seen in references and unfortunately has been the subject of reproduction. It consists of unit number below the letter “R”. The numbers are either cut out or embossed. We will refer to this as type 3

The helmets are generally made of an Ersatz substitute material. Most of them are made out of filz. However they have been documented with cork covered with cloth. They were worn with an M15 type bayonet spike base that is ventilated. There is a ventilation cover on the rear spine. There are M 91 posts made of gray metal. They are found both with and without a visor trim and the chin straps are made of leather.

That helmets were often worn with a long neck covering. This is known by several names but we will call it “Nackenschutz”. The Nackenschutz was a separate item and attaches to head gear through a separate band and buckle. Lacarde makes reference to the band being elastic. The Nackenschutz did not need to be worn with a helmet.

iii

iii

Johansson has an example of a type 3 in his book “Pickelhauben” on page 60. It is a filz helmet with a ventilated spike base and a scroll with cut out letters. He calls the metal “pewter”, and states that the R22 designation stands for Infantry Regiment 22. There is no visor trim. It has a black leather chinstrap with gray metal buckles. On page 61, he shows a type 2 used on a cork helmet with a white cloth covering. This appears to say 116. It has a brown leather chinstrap with no buckles. iv

Lacarde in volume 1 page 112 shows a type 1A with a number 212, a visor trim and two gray buckles. He mentions steel fittings. v (This helmet is from Fort de la Pompelle and a shown later in the article)

Kraus in his book “The German Army” shows an example on page 70 that is a type 2, with the number 135. The helmet is clearly marked to Bekleidungsamt XVI. Kraus goes on to admit that this helmet is of unknown origin. It has a leather visor trim, a black chinstrap and cockards. On page 71 he has a helmet that does not have the scroll but has a unit number painted directly onto the front of the helmet. This helmet also has a Nackenschutz and is clearly marked to the 205th Pioneer Company. vi The Belgian Army Museum has a similar helmet shown here in a picture taken by Max Chaffotte. So far I have been unable to determine the source of this helmet.

In the Wurrtemberg book — Konigreich Wurtemburg die Militärische Kopfbedeckungen — on page 56 there is a picture of a soldier wearing a type 1 with a Nackenschutz but no visor trim. The picture is attributed to Gebirgs Maschinengewehr Abteilung 250, this is a Wurrtemberg formation created 7 September 1915. vii

On page 87 of the two-volume book by Kraus there are a series of diagrams. These include a type 3 R116, a type 2 227, a type 3 R22, and a type 2 that looks to be 237. viii

Where

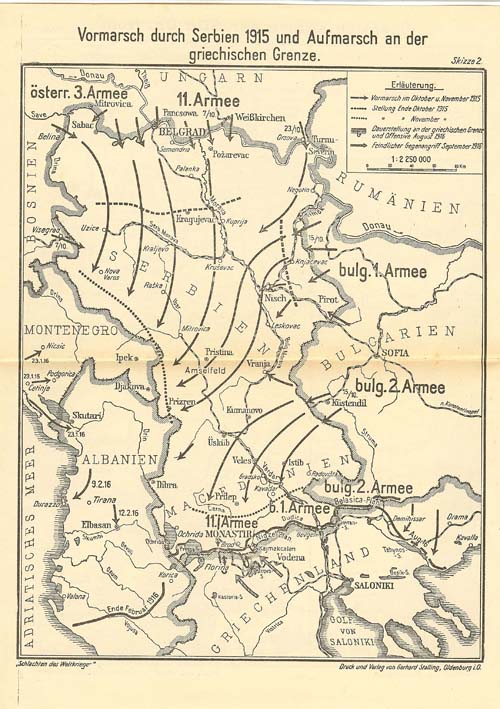

References are full of two different locations for these helmets. Serbia and Macedonia.

Both of these are illustrated on this map. Everyone knows where Serbia is however this was the fourth invasion of Serbia in 1915. Macedonia is a different concept. You can see Macedonia on the very southern border of Serbia. What exactly is Macedonia is still debated. Bulgaria, Serbia and Greece all had land claims to parts of Macedonia. Each country’s different interpretation of what Macedonia was continues to this day. A small bit of trivia is that the modern country of Macedonia is actually known as FYROM. That abbreviation stands for the Former Yugoslavian Republic of Macedonia. That name was finally settled on after vehement disputes over who owned Macedonia between Bulgaria, Greece and the new country.

For our purposes, Macedonia is the front between the Central Power Armies and the Entente armies headquartered in Salonika.

ix

When

This can be a very sticky question. The original Prussian order from the War Minister was dated to August 1915. The invasion of Serbia that these troops allegedly were involved in started in October of 1915. The very first picture on this page is dated November 1915. The manning of the Macedonian frontier continued until the end of the war. It is unclear when helmets were no longer worn on the Macedonian front. Below is a picture of Gebirgs Maschinengewehr Abteilung 249 in Macedonia dated 11/7/1916 wearing a tropical helmet. The gentleman on the right wrote a series of postcards from April 1917. Pictures from Palestine show tropical helmets without scrolls still being worn in 1918. The Prussian War Minister decreed that there would be no more use of filz helmets on the front after August 15, 1917. Did this include Macedonia?

This is the depot in Alexinac that was established for these units. The writer confirms the location, although misspelled. The depot was opened around May 7th, 1917. It comprised personnel for training, medical care etc.

Not much detail there. However, the guy with the big helmet poses another question. Did these units switch helmets?

Who

Gebirgs Maschinengewehr Abteilung

The original Prussian order from the War Minister established scroll helmets for the Gebirgs Maschinengewehr Abteilung 211 through 250. There are several pictures of these mountain machine gun battalions. They were not assigned to divisions and are somewhat difficult to track. All of the pictures of the Gebirgs Maschinengewehr Abteilung have a type 1 and 2 helmet Wappen. While there are questions of timing there is no question really about these machine gun units having a scroll helmet. There is documentation that says that GMGA 211 thru 250 had numbered shields. There is an example of a helmet with a type 1A plate for 212. There are diagrams in references for a type two 227, and 237 and a picture of a soldier wearing a 218, 228, 232, 238, 246, 247 and a 250 type one. The entire empire contributed to these.

Württemberg: GMGA 250

Saxony: GMGA 249

Bavaria: GMGAs 206-209 (later GMGA 262), and 248

Prussia: GMGAs 201-205, 210-247, 251-255 (in 1918, 15 of these these bacame the new units 260, 261 and 263-265)

Order of battle information on these machine gun units is very hard to come by and must be pieced together. There are no unit histories for these units. GMGA 201 through 209 were formed primarily of cavalry division’s on the Western front.GMGA 210 and 251 also seem to have been assigned to Belgium on the Western front. It appears as though GMGA number 242, 244, 245 and 246 were attached to the sixth infantry division in 1917 and transferred out of Macedonia. There is a picture of GMGA 203 in Macedonia in Dec. 1916.

Another researcher by the name of Robert Hinsley has extensively dug into these GMGA. The following paragraphs and conclusion is a quote from Robert that was placed on pickelhaubes.com.

In the following I will translate what is written about the GMGA formation until 1917, leaving out some lenghty passages (marked …) and marking my own notes with square brackets. The orders are usually referenced via footnotes:

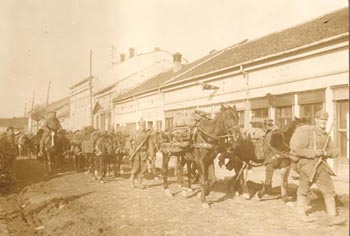

“Very soon after war begin the need for special machinegun units besides the regular MG issues for the troops fighting in mountain terrain became obvious in the Vosges and the eastern front. Only whith these it was possible to move firepower quickly to the required places, to support own actions or defend stretched frontlines against superior enemy forces. Upon an urgend request of the OHL [Oberste Heeresleitung, i.e. highest army command], fourty GMGAs numbered 211 to 250 were quickly assembled by the MG training course Döberitz beginning in August 1915. 18 of these units had to be deployable by Sept. 9th, the following 22 by Sept. 20th 1915 (Pr. Kr. Min. Nr. 2002/8. 15 A. 2 D from August 21st, 1915). The mobilization of these troop was so important that all other requests had to stand back and the outfitting of other MG units that were planned for August and September was delayed. All personnel and carriage animals that had been sent to Döberitz for other reasons were assigned to the first 18 GMGA units (Pr. Kr. Min. Nr. 976/8. 15 A. 2 D from August 12th, 1915). The following 22 GMGA units were equipped with personnel and horses by the Stellv. Gen. Kos. [assistant general commands?] by Sept. 7th 1915, with Württemberg providing one of these units. The personnel had to be of good health and suitable for action in mountain terrain. The special mountain equipment and the uniforms were provided by the Pr. Kr. Min. (Prussian war ministery), guns, harnesses and ammunition by the Gew. Prüf. Kom. [Gewehr Prüf-Kommission, i.e. an arms inspection commision?] resp. the field maintenance depot. The mountain MG personnel received the gray-green uniform of the machinegun units with the units numbers on the shoulder flaps, and experimentally a lighweight helmet of felt with matte fittings, ventilation and a neck flap (Pr. Kr. Min. Nr. 1960/11. 15 B. 3 D). The GMGA units were organized in 2 platoons with 3 machineguns each and had a required strength of 4 officers, 175 other ranks, 85 horses (including 48 carriage animals) and 7 vehicles.

Upon this order the personnel for the Württemberg GMGA 250 was assembled at the 1. Ersatz machinegun company 121 in Münsingen and send to the MG training in Döberitz on Sept. 5th. By Sept. 15th the unit was regarded to be mobile and already 14 days later on Oct. 1st it was deployed to the 11. army in order to move to the Oberkommando Mackensen from southern Hungary and participate in the offensive against Serbia.