Depot Marks

Depot Marks

Joseph Robinson and Maxime Chaffotte

22 June 2007 –update Dec. 2014

(This is an international effort. Maxime Chaffotte and I are trying this together. We welcome your improvements!)

We have seen all sorts of stamps and marks on the back visors of issue helmets. By reading the mark much can be learned about the history of the helmet. Private purchase helmets might possibly have a maker’s mark or a size and maybe the owner’s name written in. However, issue helmets seemed designed for stampings from their creation. Understanding these marks is difficult but we can at least explain some of them. Not all helmets were marked the same. Conventional wisdom created the wrong impression when Bowman called these “maker’s marks” in his books. Let us try to clear this issue up a little. These are not maker’s marks. These are identification marks used by the supply system. Makers marks are a different entity and can be seen in a separate article: http://www.pickelhauben.net/helmet-makers

Directives for uniforms, clothing and equipment started with the Prussian War Ministry. Constitutionally, they were empowered to direct the other war ministers. Major changes required an endorsement by the Kaiser (major changes) or the “Kriegsminister” (minor changes). Those changes were published as an “Allerhöchste Kabinettsorder” (A.K.O.) (supreme cabinet order) in the “Armee-Verordnungsblatt” (AVB) issued by the Prussian War Ministry. The AVB are full of those uniform changes in detail. The other three kingdoms took the AKOs found in the AVBs and published them as “Allerhöchste Entschließung” (A.E.), “Allerhöchste Order” (A.O.) or “Allerhöchster Befehl” (A.B.) in their respective local AVB “Verordnungsblättern”. Therefore, adoption of AKOs took place at different times and to different degrees. Saxony, Württemberg, and especially Bavaria maintained some freedom in regards to AKOs. The units attributable to duchies and principalities were part of the Prussian army but in some instances origins were maintained in markings. So you had the primarily Prussian Corps listening directly to the Imperial AKOs and the XIII Corps (Württemberg), XII and XIX Corps (Saxony) and the Bavarians doing variously different things. Also any marking rules were taken as suggestions not mandates. All uniform pieces were specified in detail in the “Bekleidungsordnungen” (Bkl.O.) for NCOs and ORs or in the Offizier Bekleidungs-Vorschriften (O.Bkl.V.) for officers.The officer regulation is translated into English in Appendix A. of Randy Trawnik’s book.

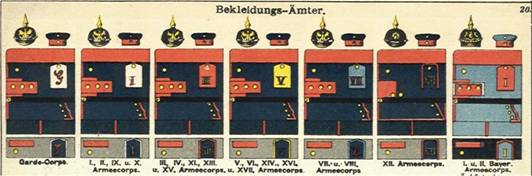

Then the Prussian war ministry issued samples of the uniform or equipment to the army corps. Each corps had a small but very important supply unit called the Bekleidungsamt (BKA or BA). The samples were called Probe and the army corps BKA received them and called for bids from the suppliers of their army corps district. The bids were designed to produce the respective piece of uniform or equipment according to the specifications given by the samples. The Bekleidungsämt had to accept the bids of at least two suppliers per article to avoid monopolies and the image of corruption.

The system of Probe’s or examples changed a lot by kingdom and morphed over time. Do not get the impression that all contractors had to make perfect copies of the Probe. They had to approximate it and of course there were manufacturing differences. This really came into effect once replacement or ersatz helmets came into play. Collectors who see a Probe item, and expect all other helmets of that type to match make many mistakes. Look at the various manufacturers of Kürassier helmets. Those made by Lachmann tend to be identifiable from a distance from the other manufacturers due to the vertical nature of the neck guard. Yet both kinds of helmets were patterned off the same Probe.

It seems however, that 4 of the 25 Corps did not at first glance have an independent BKA. The last army corps to be added XVIII, XX, XXI and III Bavarian Corps seemed to have doubled on an older BKA. We still had 21 BKA. This gives rise to our first mark which was BA. BAXIV for example is the mark for the BKA of the XIV Corps. This example shows BA III.

As each army corps developed their own stamping method is relatively easy to construct similarities by corps. The Prussian BKA frequently had the BKA initials, the corps number and perhaps the date inside of a rectangular box. the box was not always present and the numbers though normally written in the Roman method they are also found with Arabic numbers. These are normally but not always found on the rear visor of a helmet. The Bavarian marks seem to be found in the dome of the helmet for Bavarian Corps I and Bavarian Corps II. Bavarian Corps III seems to have varied significantly when they finally created a BKA in 1916. Rather than a Bekleidungsamt the clothing department in that corps was known as the Bekleidungs Depot (BD) and had a significantly different mark.

The BKA was not standard in size or organization but varied by corps and nationality. In some cases civilians populated the “handwerk” section. Prussian Corps had about 75 NCO and OR types while Bavarians had 200. Wurttemberg’s Corps and the two Saxon Corps had 28 NCOs but no ORs each.VIII Corps in Coblenz seems to have picked up much of the slack in the missing BKAs. They did parts of XVIII Corps, parts of XXI Corps and assorted other units like the NCO school. II Corps picked up XX corps. XV picked up most of XXI Corps. XI Corps picked up Regiment 87 & 88 from XVIII Corps as well as both Eisenbahn Regiment 2 & 3. Mostly I Bavarian Corps but some of II Bavarian Corps picked up Bavarian III Corps. BKAs seem to have come into their own in waves as Corps HQ’s were created. Most corps through corps XV in 1888. Corps XII, XVI-XIX in 1892, Bav. III in 1889. What that signified was a significant shift of how things were marked. As the territory in total did not expand, but the number of Army Corps districts did. Some units that were in Corps number A were moved to Corps number B along with their helmets. The BKA did not mark the helmet at all until something like 1902 and before that the first mark was made to detail regiment and issue date. BKA marks are mostly found in ink. The earliest known use of ink alone is 1873. These were relatively uncommon, and ink did not become the mainstay until almost the 1890s.

Each Clothing Office had a head Beamte in field officers rank and several further officers – all active follwing the reorganisation of the late 1890’s. They were further staffed by a number of officials depending on size, typically in a large office – a Bekleidungsamt-Rendant, 5 Bekleidungsamt-Inpektoren, 1 Bekleidungsamt-Unterinspektor and 15 officials with equivalent NCO rank. Much of the work force hired by the Bekleidungsamt were female. From Dr. L. Meyer`s “Grundzüge der Deutschen Militärverwaltung“, published in 1908. In remarks concerning mobilization of Bekleidungsämter (translation by Glenn Jewison):„The re-enforced Handwerkerabteilung is organized into four parts: Betriebsabteilung I (shoemakers), Betriebsabteilung II to IV (Tailors), which are each further organized into four companies.”

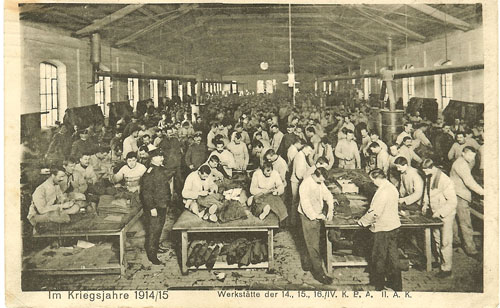

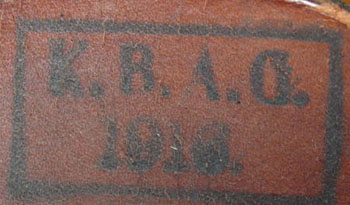

With the outbreak of hostilities the Bekleidungsamt organization exploded in size. They grew to regimental size, commanded by a Colonel, consisting of companies and battalions (Betriebsabteilung). A Bekleidungsamt consisted of 85 officers, 50 Beamte and 3300 workers. The Guard Corps erected a wartime garment department (Kriegs-Bekleidungsamt Gardekorps – K.B.A.G.).

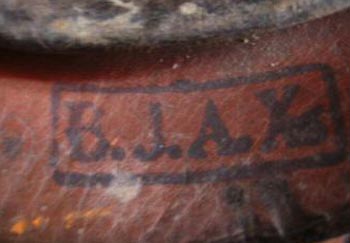

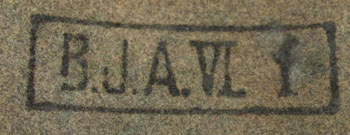

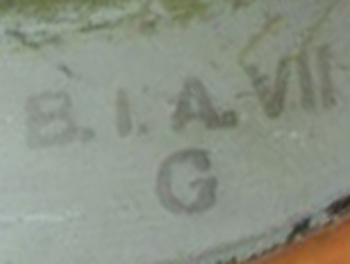

Each Clothing Office had a smaller repair organization (Bekleidungs Instandsetzung BIA or BJA) after mobilization. The Bekleidungs Instandsetzung had only seven officers six Beamte and 300 workers. It was commanded by Captain.

III Bavarian Army Corps created a Bekleidungs Depot (BD) and in Prussia where the XVIII, XX, and XXI corps had no Bekleidungsamt they developed what was called a Reserve Bekleidungsamt (RBA). The reserve Bekleidungsamt seems to have been identical to the other Bekleidungsamt organizations but used different marks as in the example below, for XVIII Corps. I cannot readily explain the difference in name except to note that there had been no Bekleidungsamt in these military districts previously.

The Bekleidungsamt fell under the jurisdiction of the deputy commanding general in the Military District. As each Military District Deputy Commanding General was basically an independent satrap — markings differed by corps Military District. Differences abounded. Location of the stamp, method used, size, and abbreviations differed. Most pre 1895 type helmets had the marking pressed or stamped into the leather. For some there were also painted on marks often in white paint. So you could have different locations, sizes and methods. Do not expect a uniform method of marking. This example shows a mixture of white paint and pressed in marks.

The Bekleidungsamt marking allegedly signified the acceptance of the helmet from the manufacturer but it seems as though it was applied, just prior to being issued to a lower command rather than on acceptance. It could also have a manufacturers stamp or sticker. You would also have a date (in theory) of when the helmet was inspected. As helmets had a wear out date this could ground the inspector in how long this item had been around. The Saxons of XII and XIX Corps also sold helmets marking them as bought.

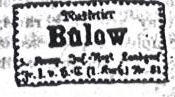

The BKA then issued the helmet to the Regiment. The regiment then either marked the helmet or did not. There are several different types of regimental markings. The easiest to understand marking is one that says IR # for Infantry Regiment. It is also common to see JR# using the common J to replace I in an effort to avoid confusing it with l.

There is also a common method of #R which is also known as the “Saxon method.”. There are also regimental markings tied to geographic regions and honorary titles.

Regiment passed equipment down to the company level. Battalion and company could be marked into the helmet. These marks varied immensely. Some were not marked by company. Some didn’t even have battalion.Few helmets had markings from all levels but here is an example of 133rd Regiment, 3rd Battalion, 9th Company from 1898

The helmet could be marked at this time with a roman numeral called a garniture mark. This indicated the “goodness” of the helmet. A good model would be marked with one Roman numeral and then further garniture marks would be added as inspections took place and the condition deteriorated. Grades were from I-V with I being the best. For most uniform parts the company had to keep three sets of each article on stock. The best set (erste Garnitur) was only issued for mobilization or parade and was recollected again after parade. Second set (zweite Garnitur) was the “better” service uniform and third set (dritte Garnitur) was the drill and exercise set. For spiked helmets there were only two sets. When soldiers were sent home after service the regiments had to discharge them with a complete uniform (no helmet but cap – Krätzchen) – which was certainly not erste Garnitur.

A leather helmet was supposed to be good for 10 year. When the soldier’s enlistment was up in 2 years the helmet went back to the Kammer. I do not have the stock levels for Kammers but it makes sense that excess helmets were sent back up to the BKA. The subordinate leaders would of course keep the good ones and send those in worse shape back. When it arrived back at the BKA it could be re-inspected and a new garniture grade issued if it had degraded in the previous owner’s use. It was then ready to re-issue. A new date and possibly a new garniture mark added. This example on the left was issued three different times. The company was required to keep two helmets, one that was issued to the soldier. Not all helmets had these marks. According to the estimated life span of the equipment the regiments received an annual budget to purchase equipment from the army corps. If the regiment managed to save money from this budget they could spend it on extra equipment, so called “außeretatmäßige Stücke”. That explains how all those many, many anomalies of regiments found their way into the “official” equipment of a unit. E.g. some cuirassier regiments kept breast armor unofficially after 1888 which had to be paid out of those unofficial savings. The NCOs responsible for the Kammer (Bekleidungs-unteroffizier) were responsible for keeping the company stock (Bekleidungskammer) proper, clean – and profitable! The one on the right is garniture III.

Not only were helmets issued back into the system by the repair facilities with a BIA mark there are other marks used on release that cause confusion. The most common of these is the letter F. The letter is found on many BIA marks as well as BKA marks. it is found both in the capital letter F and the smaller letter f. This was an inspection mark that followed a shorthand wartime garniture system. Because many of the wartime helmets were released from the BIA with repairs this marking is often confused with “repaired”. However, they were also inspected and released from the BKA. The letter in small or capital spelling means “felddienstbrauchbar” or field/war serviceable. The lower-level garniture inspection resulted in code “G” meaning “garnisonsdienstbrauchbar” or garrison / home serviceable only. This marking was often used for obsolete helmet types. This mark was far from universally used. As you as you will reallyThis was a wartime expedient. This replaced the garniture system with just two grades – either F or G.

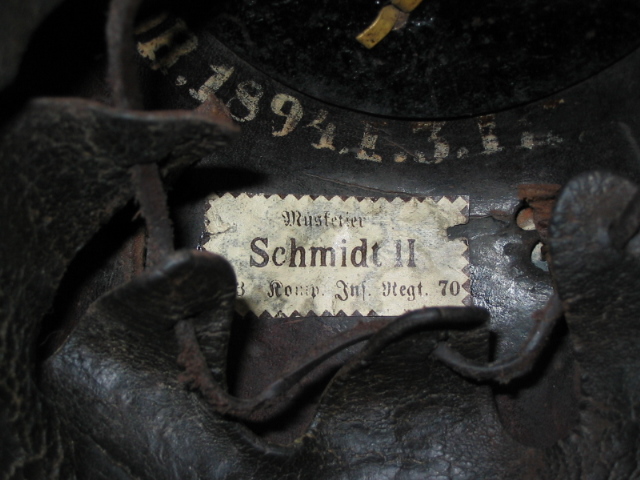

The tag shown below is not a maker’s mark. These stickers could be purchased at the military effects store. This is a private tag to mark your “stuff”. They often have great information on them. You can see the name, rank, regiment, and company on the second example. This guy is named Schmidt II which means he is the second Schmidt in the company.

Regularly the same suppliers supplied the same corps. While at first this might mean nothing, most makers had similar grommet measurements for their helmets. So all wappen supplied by that maker should have the same measurements between mounting hardware. In a case like the maker Julius Jansen he supplied many of the helmets for both XIV and XV corps. So you can have a Prussian eagle and Baden Griffin on an issue helmet made by Jansen that have the same distance between mounting hardware. The pictures below are of two M15s from Jansen and the two wappen though different have grommets the same distance apart.

Just when you thought you had a handle on it you find other examples that are outside the norm. This one has white paint in the crown of the helmet dated 1916. For some reason Baden Regiment 111 seems to have always used paint (white or black) in the top of the helmet.

Why would my helmet have no marks? There are several reasons and one could buy a Diensthelme that looked an awful lot like an issue helmet but as a private purchase item there would be no marks. Helmets not issued out to units would also bear no marks. As the war went on I think standards in BKA’s slipped to keep pace with the volume so war time helmets are less likely to have marks. As Pickelhaube were phased out in favor of steel helmets inflowing inventory would be stockpiled. Manufacturers were completing contracts and units were being issued steel helmets. Helmets that were stockpiled and not issued would not have a marking. In the same vein many of these stockpiled helmets were supposedly the supply for the thousands of war bond helmets found in the USA. So thousands of good unmarked helmets found their way into family hands.

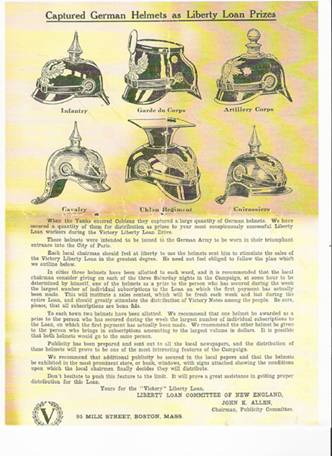

Friday Feb 7, 1919 THE STARS AND STRIPES newspaper, Page 1, Column 1:

“85,750 Shiny Ones on Way to American

Prussian Guards’ Helmets will help sale of Liberty Bonds

The doughboy guards at Coblenz who kept the keys to the German warehouses where 85,750 Shiny Prussian Guards helmets were stacked are restored to good nature. They eat normally, and no longer dream of great helmet robbery mysteries. For the helmets are out of their custody at last and on their way back to the States. The warehouse keys arent’t needed any longer. The helmets are to be handed out back home to buyers of bonds of the Fight Liberty Loan.

Meanwhile, traders on the AEF souvenir bourse are eagerly watching the tape for the first transatlantic quotation on Helmets.

Word of the 85,750 helmets in one buiding leaped back through the AEF almost before the advance guard of the Third Army settled in Coblenz. Mails from the rear areas of the AEF to the Army of Occupation grew unaccountably large. Every man in the A of O had from six to 60 friends whose latest letters always said after speaking pointedly of lugers and mausers and iron crosses: “And of course I am relying on you to get one of those 85,000 helmets for me.”

The pressure of visitors to the warehouse grew so strong that the chief salvage officer at Third Army Headquarters posted a big sign: No More Helmets Given Out.” (The citation was found by Keith Gill.)

Some of the abbreviations used

A.A. Aufklärungsabteilung

Abt. Abteilung

A.K. Armee Korps

A.M.K Artillerie-Munitions Kolonne

A.N.R. Armee Nachrichten Regiment(signal)

A.R. Artillerie Regiment. Mostly foot artillery but found on one Field Artillery.

B. Battalion

B.A. Bekleidungs Amt- (Followed by a roman or Arabic numeral Corps number)

B.A.G. Bekleidungs Amt Garde

B.A.O Bekleidungs Amt Ostasien

Bat. Batterie

Bay. Bayrisch

B. Battalion or Batterie

B.D. Bekleidungs Depot (Bav. III)

B.I.A. Bekleidungs Instandsetzung (Followed by a roman or Arabic numeral Corps number)

B.I.L.R. Bavarian Infant. Lieb Regiment

B.J.A. Bekleidungs Instandsetzung (Followed by a roman or Arabic numeral Corps number)

BKA Bekleidungs Amt- (Followed by a roman or Arabic numeral Corps number)

Br. Brigade

Brok. Tr. Brücken Train

C. company — old spelling

C.G.R.9 Colbergsches Grenadier Regiment 9

Chev. Leg Chevaulegers

Dic. Division

D.R. Dragooner Regiment

DRGM Deutsches Reichs-Gebrauschs-Muster = registered trade mark in germany

DRP Deutsches Reichspatent

E.B. Ersatz Battalion

E.L.I.R. Ersatz Landwehr Infantry Regiment.

E.R. Eisenbahn Regiment

E.R.I.R. Ersatz Reserve Infantry Regiment

Eisb. R Eisenbahn Regiment

Esk. Eskadron

F or f felddienstbrauchbar–Field wearable (or serviceable)

F.A.R. Feld-Artillerie- Regiment

FB Fusilier Battalion

Fd A.R. Feld-Artillerie- Regiment

Fd. Las Feld Lazarett

F.F.K. Fortress Ferensprecher Kompanie

Flg. B. Flieger Battalion

Fpk. K. Fubrparl Kolonne

F. R. Fusilier Regiment

Fr. Wag. Futter Wagen

F.S. Feld Schmeide

Fs AR Foot Artillery

Fuss A.R. (B) Fuss Artillerie Regiment (Batallion)

G or g garnisonsdienstbrauchbar garrison / home serviceable

Geb. Jäg. R. Gebirgs Jäger Regiment

Geschw. Geschwander (wing)

G.F.R. Garde Fusilier Regiment

G.G.R. Garde Grenadier Regiment

G.G.R.5. 5th Garde Grenadier

3.G.G.K.E. Königen Elisabeth Garde Grenadier

4. G.G. R. K. 4th Garde Grenadier

4.G.G.R.K.A. Königen Augusta. Garde Grenadier

G.J.B. Garde Jäger Battalion

G.K.R. Garde Kürassier Regiment.

G.P.B. Garde Pioneer Battalion

G.R. Grenadier Regiment or Garde Regiment

Gd. Garde

G.R.z.F. Garde Regiment zu Fuß

G.S.B. Garde Schützen Battalion

G.T. Garde Train

H.R. Husaren Regiment

I.L.R. Infantry Lieb Regiment

I.M.K. Infantry Munitions Kolonne

IR Infantry Regiment

5/I.R.88 5th company Infantry Regiment 88.

II/I.R.88 2nd Battalion Infantry Regiment 88

J.B. Jäger Battalion

J.R. Infantry Regiment

K. Kompagnie

K.A.G.G.R.1 Kaiser Alexander 1st Regiment Garde Grenadiers

K.B.A. Kreigs Beckleidungs Amt

K.B.A.G Kreigs Beckleidungs Amt Garde

K.F.R. Kaiser Franz Regiment

K.F.G.G.R.2 Kaiser Franz 2nd Garde Grenadier

Krad. Schtz. Btl. Kraftrad Schutzen Batallion.

Krnk. W. Kranken Wagen

Kür. R Kürassier Regiment

L.B.A. Landwehr Bekleidungs Amt

Lds. Landsturm

Ldw. Landwehr

LG Landgendarme (territorial police) [also Landes Gendarmerie]

L.G.R.8 Lieb Grenadier Regiment 8

L.I.R. Landwehr Infantry Regiment.

M.G.A. Maschinengewehr Abteilung

M.G.K. Maschinengewehrkompanie

MPB 4 Magdeburgisches Pionier-Battalion Nr. 4.

OJR 78 Ostfriesische Infantry regiment 78

OJR 91 Oldenburg Infantry Regiment 91

P.B. Pionier-Battalion

Pi Pionier-Battalion

Pion. B. Pionier-Battalion

PI. KP. Prussian Pionier-Battalion

P.R. Rekrutendepot des Pionier-Battalion or Pioneer Regiment

Prov. Proviant (supply)

R. Regiment (A mark of R87 could be either 87regiment or RJR87.)

R. Reserve Infantry Regiment. (A mark of R87 could be either 87regiment or RJR87.)

R.B. Reserve Battalion

R.C. Reserve Company

R.B.A. Reserve Beckleidungs (followed by a corps number)

r… Reitende ( Horse Artillery)

Rdf. C. Radfahfer Kompanie

Res. Reserve

R.I.R. Reserve Infantry Regiment

RG Reich’s Gendarme

R.J.B. Reserve Jäger Battalion

R.J.R Reserve Infantry Regiment.

Schwf. B. Scheinwerfer Battalion

Schw. R.R. Schweres Reiter Regiment

T.A. Train Abteilung

T.B. Train Battalion

Tel. Telegraph

Telgr. B. Telegraph Battalion

Tr. Truppenubungsplatz. (Training ground)

U. R Ulahnen Regiment

z.F. ZuFuss

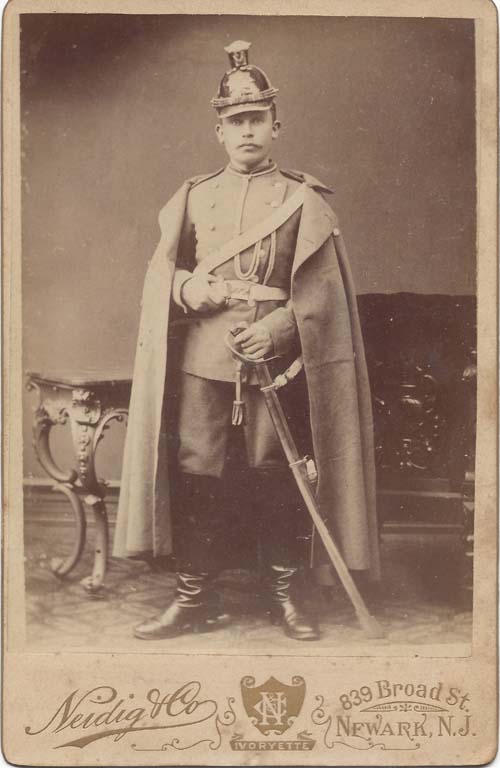

A Note on LG Helmets

Many helmets are mistaken for Garde helmets. They have a guard Wappen with the star and the marking LG on the inside. These are not military helmets strictly. They are police helmets. The Landgendarmerie or LG was a police unit mostly in rural areas under Prussian administration. The chain of command of the Gendarmerie went to the War Minister not to the Ministry of the Interior. These gentlemen were civil servants who had spent at least nine years in the Army. They had a mobilization mission and are found in some pictures as Feldgendarmerie. There were both mounted and dismounted LG. Mounted LG have squared visors and dismounted ones had rounded visors. Both wore the guard Wappen on their helmets.

A Wachtmeister of the 7. Landgendarmerie-Brigade. Coesfeld was in the VII. Armeekorps District, about 30 Kilometres to the West of Münster.

M91 Chinstraps & Side Posts

M91 CHINSTRAPS & SIDE POSTS

Joseph Robinson, and Amy Bellars

February 12, 2005.

Introduced in 1891, the M91 chin strap is by far the most common chin strap on helmets. They’re mostly associated with issue helmets, and leather chin straps. But officers and chin scales also were used with the M91 side posts. This was an incredibly clever design that allowed a simple hook to twist onto the helmet and stay in place. Cockades were held in place behind these strap hooks. As it turned out the frugal Germans use the same straps for the M16 helmet. The design was just that good.

A Canadian collector named Tony discovered that there was a difference between the thicknesses of different hooks. This is documented nowhere that I know of. With all the Pickelhaube references no one caught this. Trial and experience of this collector proved to uncover a difference that previously had been undocumented. We will now take this idea a bit further.

1mm thick chinstrap hooks are the most commonly seen chinstrap hooks. They are manufactured using brass, nickel and steel. They are found only on leather chinstraps meant for issue pickelhaubes. During the war officers also used to leather chin straps exclusively in the field. These are generally considered the ones used for foot troops.

These 1mm chinstrap hook fit into the normal M91 side posts of most foot pickelhaubes. When we say fit, we mean fairly snugly. The cockade that rests behind the mount or side post, does not wobble. So the area of fit between the hook and a side post is approximately 1 mm.

There were also identical hooks, 3.8 cm long, that were 3 mm wide. The side posts were thicker also to accommodate the fastening of a thicker hook.

This is a comparison of three different chin straps, made of leather with different kinds of hooks.

Here is an example of a 1 mm chin scale and a 1 mm leather strap.

You can see how snugly the M 91 hook, holds the cockade.

Bavarian helmets pose an interesting quality. The M91 hooks and side posts are all 3 mm. This is an observation based on example, and there are probably differences and exceptions. Shortly after the start of the war, all officer, chin scales in Bavaria became convex regardless of branch. These obviously required a 3 mm post if they had M91 type hooks.

Officers did indeed have M 91 posts. These are called M15 helmets and similar to the enlisted M15 helmet, they had a bayonet twist off Spike. They had a faux rosette on the side that covered the actual and 91 post itself. An easy way to tell if an officer’s helmet is an M15 type is to look at the chin scales themselves. M91 type chin scales have the three dots on them. Just like in the picture above.

Conclusion.

We are quite positive that there will be a lot of additions and changes to this. Ideas will continue to evolve, and some original notions will prove false. It seems as in the Pickelhaube game there are exceptions to almost every rule. Finding a period source on this will probably be as impossible as finding it mentioned in any modern reference. How fun collecting can be!

The Brunswick Running Horse Wappen.

The Brunswick Running Horse Wappen.

Joseph P. Robinson.

29 November 2005.

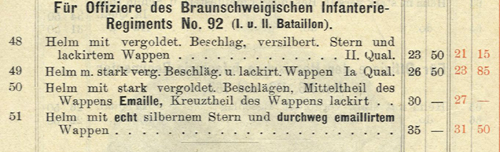

The single most popular helmet is that of the first and second Battalion 92nd Infantry Regiment, prior to 1912. The acquisition of the Neumann catalog brought up a few points about the enamel wappen. The example I will use is the very popular running horse wappen from Brunswick or Braunschweig. There have been a lot of questions about this wappen as the prices commanded by this popular helmet have soared. Arguments about paint and the amount of enamel went back and forth. Stubbs does a great job in his book, taking one apart. The general consensus was less enamel = less likely to be original. Lots of questions and lots of ideas.

What this catalog shows us is that there were four qualities of the enamel center of the wappen.

1. A helmet with gilded metal, silvered star, and lacquered wappen.

2. A helmet with heavy gilded metal, and lacquered wappen.

3. A helmet with heavy gilded metal, the center of the wappen enameled. But the cross on the wappen is lacquered.

4. A helmet with a genuinely silvered star and a totally enamel wappen.

Of course there are many manufacturers of the wappen all with its different twists. The style of horses were different. And the central post with a green top is enameled in some examples and painted in others.

I cannot attest that either of the two above examples are from Neumann. The example on the right has red in the mask of the crown. The example on the left no longer has any evidence of that color. One interesting point is that the top-of-the-line wappen cost 50% more than the bottom of the line.

In volume 1 of his excellent two-volume series. The French author Lacarde laments that there are many running horse fakes. He alludes to the fact that in some cases, the enamel is just not right. While I am positive that the author has seen some phony enamel, the catalog quote above should prove that not all of these wappen were enameled. But why so many? It certainly seems that there are more of these than one would expect from two battalions of use prior to 1912. The answer is in the landwehr. All officers under the Bezirkscommando wore this wappen. All other than active units in XCorps are suspect at the least. This excerpt from “Das Deutsche Heer” bares this point out.

|

|||||||

An American Pickelhaube

The American Pickelhaube

Joseph P. Robinson.

26 May 2005.

In late 2004, a pickelhaube sold in a small auction house in New York. This was an incredibly unique pickelhaube. Competition for the piece was fierce, and the final price was much higher than almost anyone expected. We are all familiar with American pattern spiked helmets. This is not one of them. It was a German style pickelhaube with an American front plate. It is original, not modern, not faked, in pristine condition, probably never worn, and I have no idea what it was for. It could have been a prototype. It certainly wasn’t worn much if at all. But somebody went through a great deal of expense to create this. The way wappen were made required the creation of a die that stamped the wappen from two directions. This was by no means inexpensive and was designed to literally stamp out thousands of helmet plates. The original version of this article brought two more American pickelhaube to the surface. Lately after this was published in Military Trader, The de Quesada collection provided more expertise and models of these militia helmets. First let’s look at the original officers helmet.

This helmet has all the characteristics of an M91 type private purchase German pickelhaube for an officer. The spike, only 9 cm high has the two rings common with officer ones. It has an officer style spike base with two ventilation holes. It has a round base held in place by four star studs. There are chin scales reinforced with leather, split brad rosettes, thin, private purchase visor trim, officers type rear spine, and very good liner and leather. The helmet plate is obviously fire gilded.

Also known as a ghost, this is the impression left by the helmet plate on the body of the helmet. Especially around the head, this impression is quite deep. This is what collectors call a perfect match between the plate and a helmet. This was the original plate for this body.

You can see here the rear spine, and that the spiked unscrews. The threads on the spike are very coarse.

There is only one cockade on the right hand side of the helmet. It is non-serrated and 55 mm wide. This is very similar of course to a German cockade but a non-serrated type, would almost point towards it being non-Prussian in heritage. It would be nice to imagine that this was red white and blue. The reality of it is that it’s more like red black and blue. Even with Saxon gray, which often substitutes for white, this is not gray. It is black. Same kind of chin scales as a German helmet. Same kind of officer rosette with the same measurements.

Here you see the start of a liner on the inside that has a German hat size written in pencil. The liner top is made out of a heavy-duty silk. The sweat band is a very high quality, but unmarked leather.

The visor bottoms are covered in high-quality colorings. What is really amazing is that the leather of the visors has absolutely zero crazing or heat bubbles or any marks of any kind. They are almost mint.

It appears as though the Spike base plate underneath has been removed at some point. One washer is missing and one post is missing both the washer and nut. You can see that the plate is not directly centered below the spike hole. The off-center nature of this appears to be a manufacturing issue and has no real impact at all.

The back of the wappen has two screw posts with old solder. The fire gilding is evident on the back.

Now we start to get to theories. Look at the front of this wappen. An American eagle, head turned one direction, oak leaves in one hand,arrows in another. Head pointed the direction of the arrows. This is an amazingly striking resemblance with the rank insignia of an American Colonel up through the First World War. American colonels wore a very similar spread wing eagle as their rank insignia.

This is a picture all of an American colonel’s insignia from his collar used in the early 1900’s.

You’ll notice the spread wing eagle with the head turned and one hand holding olive leaves and the other hand holding arrows. If the head is turned the direction of the arrows the nation is at war. If the head is turned the direction of the olive leaves the nation is at peace. This is a war eagle. This head turning style went out after the First World War. Today’s eagle is not nearly as detailed and much more politically correct, always looking at the olive leaves.

If you take a look at the helmet plate you will see that it is a war eagle. This brings us to the second helmet. It is an enlisted helmet with a parade plume. It came with a couple of pictures, including one of an American soldier wearing a pickelhaube. These are more like postcard cartoons, not photographs.

This is an enlisted version of the helmet. There are several key differences when compared to the officers helmet. The officers helmet appears to be completely German made with all German parts. Everything that you can consider is German in nature. It is an identical replica of a German officers helmet with an American wappen. This helmet has an issue liner, a thick visor trim, dome studs, no pearl ring, and enlisted rear back spine. However, the fittings on the helmet are not entirely “made in Germany.” In addition this eagle looks at the olive branches and is a peace eagle. The chin scales seemed to be similar to German chin scales, but the rosettes are split brad and are totally different. The liner is similar to a German liner, but is slightly different. The spike base is totally different. The leather helmet itself appears to be in 1871 type model. There are no cockades. Look specifically at the vent hole in the spike base. It is very rough and punched out.

This picture shows the rear spine, the trichter, and the rear visor, which is quite elongated similar to an 1871 pattern helmet.

Information provided from the de Quesada collection adds that there were many of these type helmets produced in low run quantities. This style is representative of helmets made by a NY firm named Deeken. These are somewhat more flimsy in the metal areas than German made helmets.

The last helmet is actually similar to an earlier German helmet M42 model. This one has a cockade that is made of leather, and is red white and blue. There is no liner and this thing has never been cleaned. The cruciform spike base is smaller than its German counterpart, and the spike itself seems rather primitive. There is a uniquely American wappen that has had a patent on it. And again is an eagle of peace. This is an excerpt from an email by de Quesada:

“The early eagle on the M1842 helmet is actually a Model 1832 Shako Plate. I have a few examples of this plate including dug versions from Second Seminole War era sites. It is possible this piece could date to the Civil War and Reconstruction eras. I have this style helmet illustrated in Civil War and Post Civil War era military suppliers catalogs.”

So here goes more theories. Research continues here. Militia units but photo proof?

From Clayton Hunt: Charleston, SC had 3 militia companies before the Civil War that wore Pickelhaubes. The Palmetto Riflemen which used the 1845 Swedish Style with silver trim, Black horsehair and Silver Skull on front. The German Artillery from sketches used the 1845 style helmet as well with brass trim, brass spike but the front appears to be a sun ray plate with crossed cannons on front. Which leaves the German Riflemen founded in 1841 who wore the Pickelhaube as well. The image from their woodcut shows an officer with white plumage on top of his helmet. I am of the opinion that you have a helmet from an enlisted man of the German Riflemen of Charleston since only officers wore plumes. All of the German units of Charleston including the German Fusiliers and German Hussars used US Eagles for plates and belt accoutrements instead of South Carolina plates from my research. The German Riflemen wore the Hanoverian dark green rifleman frocks and black pants as well. Maybe this helps and hope it does or at least adds to the discussion. I am from Greenville, South Carolina and have focused my research on units from here between 1830 and 1861.

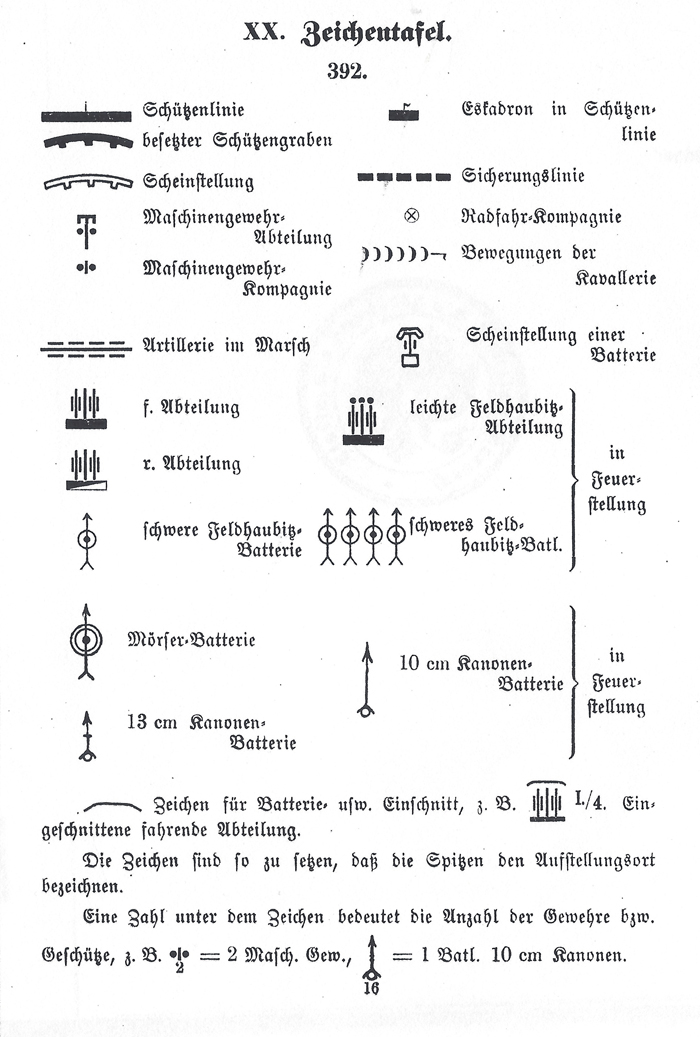

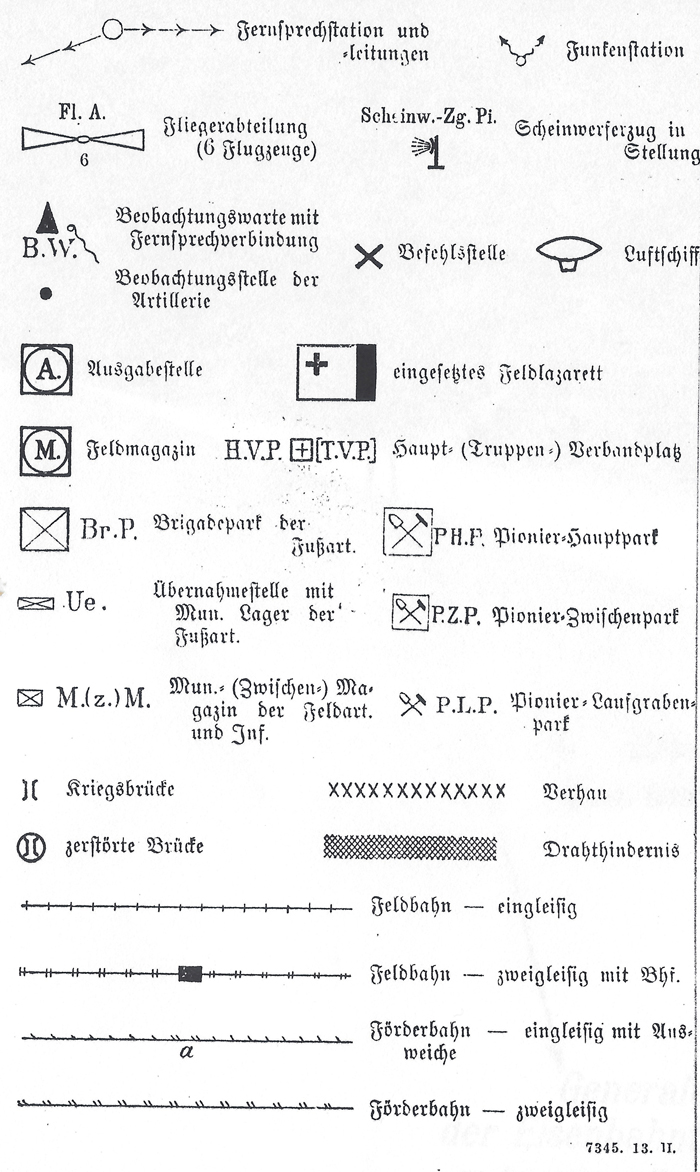

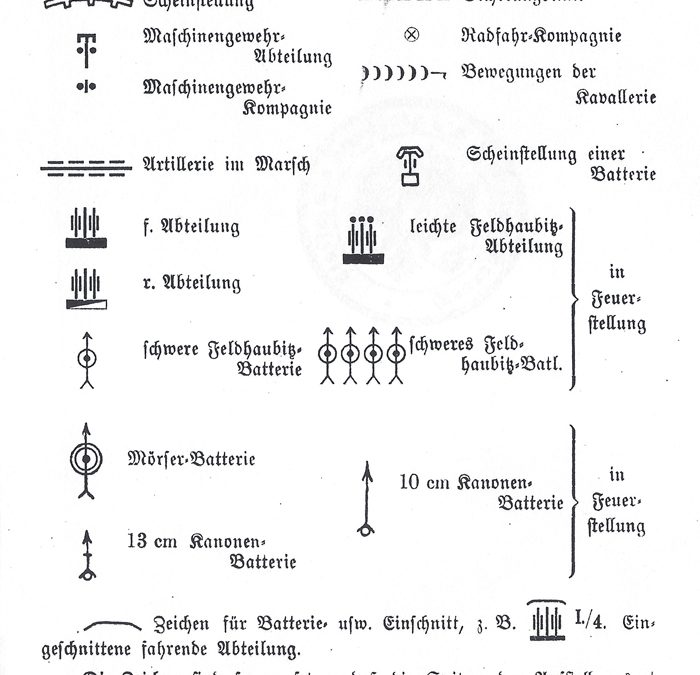

German Tactical symbols 1914

German Tactical symbols 1914

Joseph P. Robinson

This is a long-overdue very very short synopsis of the German Tactical Symbols used on maps at the very start of the war in 1914. These morphed over time however the general staff officers used these symbols for operations prior to and at the beginning of World War I. This comes directly from the general staff officer’s handbook which was issued personally to the general staff officer. It is also known as the Red Donkey. There is a copy I understand in the Potsdam archive library and we used a copy in the research and writing of “The Great War Dawning”. While the huge book seems to have everything in it the symbols were left out or did not make the cut. I thought this could be of great use to anyone looking at the maps of 1914 and maybe beyond. While we have donated most of the German research library to the University of North Texas we retained our copy of the Red Donkey. It is extremely rare and I don’t think you’ll find it easily anywhere. It is not in the bibliography of the works that I have looked for. Hope you enjoy.

Organisational & Developmental Overview of the Imperial German Infantry, 1871-1914

English-language overviews about the organization of the German Army tend to be extremely convoluted. It is helped by the fact emphasized by the renown author Holger Herwig that there really was no German Army prior to the end of the 1914 Western offensive. Rather, there were contingent armies, four in total, led by the Prussians. All of these armies expanded between the end of the Franco Prussian war and the start of World War I. There is no better research of the details of this expansion than this article written by Glenn Jewison. Originally, this was for an old website called “A Pocket German Army.” Unfortunately, that website closed down. It is our hope to present much of the data from this older site on this website. While we have added small tidbits here and there it must be understood that almost the entire work presented here was done by Glenn Jewison. If indeed you find any errors please let us know.

Regimental Names and Numbers

In July 1860, the Prussians started numbering their regiments and modified the structure in 1861. After the war of 1866, the states that Prussia annexed had their armies integrated into the numbering system. There does not appear to have been any standardization to the numbering. So, you had the integration of the Hanseatic States, Hanoverian regiments, the old electoral Hesse (Kurhessen), Schleswig-Holstein, and Nassau. That accounted for regiment numbers up to 88.

In 1867, the other states of the North German Confederation and Saxony joined the numbering system but it was not continuous nor did it follow any particular chronology. The order was the Mecklenburg Grand Duchies, Oldenburg, Brunswick, Anhalt, Saxe-Weimar, the Saxon duchies, and the other Thüringian states, covering numbers 89 to 96. The numbers for infantry regiments 97-99 were reserved for future Prussian units, which were not created until 1881. However, Saxony added their regiments to the mix starting at number 100 and this convention preceded the convention of some other states; Militärkonvention zwischen dem Norddeutschen Bunde und Sachsen vom 7. Februar 1867. Baden’s number started at 109 with Militärkonvention zwischen dem Norddeutschen Bunde und Baden vom 25. November 1870. Hesse and Württemberg followed: Militärkonvention zwischen dem Norddeutschen Bunde und Hessen vom 13. Juni 1871. Militärkonvention zwischen dem Norddeutschen Bunde und Württemberg vom 25. November 1870.

Not only were the regimental numbers juxtaposed but also the seniority of the regiments, as Hanoverian regiments retained their original founding date and other regiments traced their founding date to their parent organization. An analysis of regimental names and the movement of regiments led to some interesting anomalies. For example, Infantry Regiment 67 (4. Magdeburgisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.67) was originally from Prussian Saxony and called Magdeburgisch. It later relocated to Metz and drew its recruits mainly from the Rhineland and had nothing to do with Prussian Saxony.

The Army expansion could most easily be seen and explained by an expansion in the Army Corps system. These geographical areas were the primary methods of controlling the organization of all things Army.

The corps areas changed four times during the time of Imperial Germany. These changes corresponded to enlargements of the army and the subsequent reorganization of the units with inside the corps. Starting with 11 Army Corps in 1871, enlargements took place in 1889, 1898, 1905, and 1914 and corresponded to the increase in the number of corps. In 1888, there was 18 corps with 468,000 soldiers. In 1897 (before the next expansion), there were 20 corps and 480,000 soldiers. In 1904 prior to the next expansion, there were 23 army corps and 506,000 soldiers-Finally, on the eve of the Great War in 1914, there were 25 army corps and 661,000 soldiers. As these dates and numbers are budget and budgeting years you will find some difference between these years and the actual execution of the with all highest cabinet orders.

Organisational & Developmental Overview of the Imperial German Infantry, 1871-1914

by

Glenn Jewison

The aim of this article is to give an organisational and developmental overview of the Imperial German infantry from the time of the conlusion of the Franco-Prussian War and the unification of Germany until the mobilisation for the Great War in August 1914. This is unfortunately not a well documented subject in the English language and I have therefore borrowed greatly from various excellent German language sources which are listed at the foot of this article.This article deals with the growth of the German infantry in the period immediately prior to this date.

PRUSSIAN GUARD AND LINE INFANTRY REGIMENTS (INCLUDING SAXONY AND WÜRTTEMBERG)

At the conclusion of the Franco-Prussian war of 1870/71 the strength of the Prussian Infantry was 105 regiments allocated to 1 guard and 11 line corps as follows:

9 Guard infantry regiments:

1.Garde-Regiment zu Fuß “Erstes Regiment der Christenheit”

2.Garde-Regiment zu Fuß “Die Hammel”

3.Garde-Regiment zu Fuß

4.Garde-Regiment zu Fuß “Die Moabiter Veilchen”

Kaiser Alexander-Garde-Grenadier-Regiment Nr.1 “Alexander”, “Kartoffelschäler”

Kaiser Franz-Garde-Grenadier-Regiment Nr. 2 “Franzer”, “Bluthunde”

Königin-Elisabeth-Grenadier-Regiment Nr.3 “Elisabether”, “Kronen Esel”

Königin-Augusta-Grenadier-Regiment Nr.4 “Augustaner”

Garde-Füsilier-Regiment “Die Maikäfer”

13 line grenadier regiments 1 – 12, 89

| Name as at 1871 | Subsequent Re-naming |

| Grenadier-Regiment Kronprinz (1.Ostpreußisches) Nr.1 | Renamed 22.3.1888: Kaiser-Grenadier-Regiment Nr.1 Renamed 21.6.1888: Grenadier-Regiment König Friedrich III. (1.Ostpreußisches) Nr.1 Renamed 6.5.1900: Grenadier-Regiment Kronprinz (1.Ostpreußisches) Nr.1 |

| Grenadier-Regiment König Friedrich Wilhelm IV. (1.Pommersches) Nr.2 | – |

| 2.Ostpreußisches Grenadier-Regiment Nr.3 | Renamed 27.1.1889: Grenadier-Regiment König Friedrich Wilhelm I. (2.Ostpreußisches) Nr.3 |

| 3.Ostpreußisches Grenadier-Regiment Nr.4 | Renamed 27.1.1889: Grenadier-Regiment König Friedrich II. (3.Ostpreußisches) Nr.4 Renamed 7.9.1901: Grenadier-Regiment König Friedrich der Große (3.Ostpreußisches) Nr.4 |

| 4.Ostpreußisches Grenadier-Regiment Nr.5 | Renamed 27.1.1889: Grenadier-regiment König Friedrich I. (4.Ostpreußisches) Nr.5 |

| 1.Westpreußisches Grenadier-Regiment Nr.6 | Renamed 27.1.1889: Grenadier-Regiment Graf Kleist von Nollendorf (1.Westpreußisches) Nr.6 |

| Königs-Grenadier-Regiment (2.Westpreußisches) Nr.7 | Renamed 22.3.1888: König Wilhelm Grenadier-Regiment Nr.7 Renamed 21.6.1888: König Wilhelm I. Grenadier-Regiment (2.Westpreußisches) Nr.7 Renamed 27.1.1889: Grenadier-Regiment König Wilhelm I. (2.Westpreußisches) Nr.7 |

| Leib-Grenadier-Regiment (1.Brandenburgisches) Nr.8 | Renamed 27.1.1889: Leib-Grenadier-Regiment König Friedrich Wilhelm III. (1.Brandenburgisches) Nr.8 |

| Colbergsches Grenadier-Regiment (2.Pommersches) Nr.9 | Renamed 27.1.1889: Colbergsches Grenadier-Regiment Graf Gneisenau (2.Pommersches) Nr.9 |

| 1.Schlesisches Grenadier-Regiment Nr.10 | Renamed 27.1.1889: Grenadier-Regiment König Friedrich Wilhelm II. (1.Schlesisches) Nr.10 |

| 2.Schlesisches Grenadier-Regiment Nr.11 | Renamed: 22.3.1888: Grenadier-Regiment Kronprinz Friedrich Wilhelm (2.Schlesisches) Nr.11 Renamed 6.5.1900: Grenadier-Regiment König Friedrich III. (2.Schlesisches) Nr.11 |

| Grenadier-Regiment Prinz Carl von Preußen (2.Brandenburgisches) Nr.12 | – |

| Großherzoglich Mecklenburgisches Grenadier-Regiment Nr.89 | – |

71 line infantry regiments 13-32 and 41-72, 74-79, 81-85, 87-88, 91-96

12 line fusilier regiments 33-40, 73, 80, 86, 90

The former Saxon army had already been incorporated into the army of the North German Confederation at the conclusion of the Austro-Prussian war of 1866 and it’s regiments given the series 100 – 108 and incorporated in the XII. army corps.

With the conclusion of the Franco-Prussian war, on the 1st July 1871, the division of the Grand-Duchy of Baden was incorporated into the German army as the XIV. army corps with the newly numbered Infantry regiments 109 – 114 introduced into the Prussian sequence:

| (1.)Leib-Grenadier-Regiment | 1.Badisches Leib Grenadier-Regiment Nr.109 |

| (2.)Grenadier-Regiment Kaiser Wilhelm | 2.Badisches Grenadier-Regiment Kaiser Wilhelm Nr.110 Renamed 2.8.1888: 2.Badisches Grenadier-Regiment Kaiser Wilhelm I Nr.110 |

| Großherzogl.Badisches 3.Infanterie-Regiment | 3.Badisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.111 Renamed 18.12.1892: Infanterie-Regiment Markgraf Ludwig Wilhelm (3.Badisches)Nr.111 |

| Großherzogl.Badisches 4.Infanterie-Regiment | 4.Badisches Infanterie-Regiment Prinz Wilhelm Nr.112 |

| Großherzogl.Badisches 5.Infanterie-Regiment | 5.Badisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.113 |

| 6.Großherzogl.Badisches Infanterie-Regiment | Kgl.Preusisches 6.Badisches Infanterie-Regiment Renamed 2.8.1888: 6.Badisches Infanterie-Regiment Kaiser Friedrich III. Nr. 114 |

The Grand-Duchy of Hesse division had been incorporated in 1867 into the Prussian line as the 25. Infanterie-Division of XI. army corps with the Hessian regiments being numbered in the Prussian sequence in 1871 as Infantry regiments 115 – 118:

| 1.Infanterie-Regiment (Leibgarde-Regiment) | 1.Großherzogl.Hessisches Infanterie-(Leibgarde) Regiment Nr.115 Renamed 28.11.1906: Leibgarde-Infanterie-Regiment (1.Großherzoglich Hessisches) Nr.115 |

| 2.Infanterie-Regiment (Großherzog) | 2.Großherzogl.Hessisches Infanterie-Regiment (Groherzog) Nr.116 Renamed 5.11.1891: Infanterie-Regiment Kaiser Wilhelm (2.Großherzoglich Hessisches) Nr.116 |

| 3.Infanterie-Regiment (Leib-Regiment) | 3.Großherzogl.Hessisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.117 Renamed 15.2.1902: Infanterie-Leibregiment Großherzogin (3.Großherzoglich Hessisches) Nr.117 |

| 4.Infanterie-Regiment (Prinz Carl) | 4.Infanterie-Regiment Prinz Carl (Nr.118) Renamed 28.11.1906: Infanterie-Regiment Prinz Carl (4.Großherzoglich Hessisches) Nr.118 |

The Württemberg army corps was incorporated as the XIII (Royal Württemberg) in the Prussian sequence on the 18th December 1871 with the regiments numbered in the sequence 119 – 126:

| 1.Infanterie-Regiment Königin Olga | 1.Württembergisches Infanterie-Regiment (Grenadier-Regiment Königin Olga) Nr.119 Renamed 14.12.1874: Grenadier-Regiment Königin Olga (1.Württembergisches) Nr.119 |

| 2.Infanterie-Regiment (Kaiser Wilhelm, König von Preußen) | 2.Württembergisches Infanterie-Regiment (Kaiser Wilhelm, König von Preußen) Nr.120 Renamed 14.12.1874: Infanterie-Regiment Kaiser Wilhelm, König von Preußen (2.Württembergisches) Nr.120 |

| 3.Württembergisches Infanterie-Regiment | 3.Württembergisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.121 Renamed 18.3.1891: Infanterie-Regiment Alt-Württemberg (3.Württembergisches) Nr.121 |

| Infanterie-Regiment Nr.4 | 4.Württembergisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.122 Renamed 9.1.1892: 4.Württembergisches Infanterie-Regiment Kaiser Franz Joseph v.Österreich, König v.Ungarn Nr.122 Renamed 10.11.1906: Füsilier-Regiment Kaiser Franz Joseph v.Österreich, König v.Ungarn (4.Württembergisches) Nr.122 |

| 5.Württembergisches Infanterie-Regiment (Grenadier-Regiment) König Karl | 5.Württembergisches Infanterie-Regiment (Grenadier-Regiment) König Karl Nr.123 Renamed 14.12.1874: Grenadier-Regiment König Karl (5.Württembergisches) Nr.123 |

| 6.Infanterie-Regiment König Wilhelm | 6.Württembergisches Infanterie-Regiment (König Wilhelm) Nr.124 Renamed 14.12.1874: Infanterie-Regiment König Wilhelm (6.Württembergisches)Nr.124 Renamed 6.10.1891: Infanterie-Regiment König Wilhelm I. (6.Württembergisches)Nr.124 |

| 7.Linien-Infanterie-Regiment | 7.Württembergisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.125 Renamed 20.3.1888: Infanterie-Regiment Kaiser Friedrich, König von Preußen (7.Württembergisches)Nr.125 |

| 8.Linien-Infanterie-Regiment | 8.Württembergisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.126 Renamed 25.4.1891: Infanterie-Regiment Großherzog Friedrich von Baden (8.Württembergisches)Nr.126 |

The XV army corps was formed in Straßburg in Alsace-Lorraine on the 20th March 1871. The following Prussian regiments were transferred to it:

25, 42, 45, 47, 60, 92 as well as Saxon, Württemberg and Bavarian troops.

The following new regiments were formed by order of the all highest cabinet orders of the 24th March 1881 to the 1st April 1881 through the transfer of personnel from existing units:

1.Oberrheinisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.97

Metzer Infanterie-Regiment Nr.98

2.Oberrheinisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.99

Danziger Infanterie-Regiment Nr.128

3.Westpreußisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.129

1.Lothringisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.130

2.Lothringisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.131

1.Unterelsässisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.132

These were at first distributed throughout the existing corps. Since the end of March 1884 until the end of March 1888 in accordance with the all highest cabinet orders of 11th March 1887 to April 1887, they with the newly established regiments 135-138 were assigned to the XV. Army corps, with the exception of regiments 128 and 129 which remained with the I. and II. Corps respectively.

Regiments formed by order of the all highest cabinet order of 11th March 1887:

3.Lothringisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.135

4.Lothringisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.136

2.Unterelsässisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.137

3.Unterelsässisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.138

Also in April 1887, the following 12 Prussian regiments were authorised a fourth battalion in the strength of four rifle companies (13., 14., 15., 16.):

13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 39, 40, 53, 65, 80, 83, & 129.

In accordance with all highest cabinet order of the 1st February 1890, these fourth battalions were used to form the following prussian Infantry regiments 140 – 144:

4.Westpreußisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.140

Kulmer Infanterie-Regiment Nr.141

7.Badisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.142

4.Unterelsässisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.143

5.Lothringisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.144

By order of the all highest cabinet order of 28 July 1890, the following regiment was formed by 1st October of that year through the transfer of personnel of regiments in the 8., 16., & 21. divisions:

Königs-Infanterie-Regiment (6.Lothringisches) Nr.145

As at the 1st April 1890 the order of battle included the newly formed XVI. and XVII. army corps as follows:

XV. Armee-Korps (Straßburg i E.) Regiments 60, 97, 99, 132, 136, 137, 138, 143.

XVI. Armee-Korps (Metz) Regiments 17, 67, 98, 130, 131, 135, 144, 145.

XVI. Armee-Korps: (Danzig) Regiments 5, 14, 18, 21, 44, 61, 128, 141.

In accordance with the all highest cabinet order of 11th August 1893 all extant infantry regiments were authorised to form a fourth battalion in the strength of two companies (13. and 14.) with a personnel strength of 8 officers and 193 NCOs and privates. As ordered by cabinet orders from 31st March to 1st April 1897 these so-called fourth half-battalions were used to form new regiments, at first in the strength of only two battalions each:

5.Garde-Regiment zu Fuß

Garde-Grenadier-Regiment Nr.5

1.Masurisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.146

2.Masurisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.147

5.Westpreußisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.148

6.Westpreußisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.149

1.Ermländisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.150

2.Ermländisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.151

Deutsch-Ordens Infanterie-Regiment Nr.152

8.Thüringisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.153

5.Niederrheinisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.154

7.Westpreußisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.155

3.Schlesisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.156

4.Schlesisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.157

7.Lothringisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.158

8.Lothringisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.159

9.Rheinisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.160

10.Rheinisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.161

3.Hanseatisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.162

Schleswig-Holsteinisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.163

4.Hanoversches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.164

5.Hanoversches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.165

Infanterie-Regiment Hessen-Homburg Nr.166

1.Oberelsässisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.167

5.Grossherzoglich Hessisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.168

8.Badisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.169

9.Badisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.170

2.Oberelsässisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.171

3.Oberelsässisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.172

9.Lothringisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.173

10.Lothringisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.174

8.Westpreußisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.175

9.Westpreußisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.176

An example of the way in which these new regiments were formed can be shown by the case of 5.Garde-Regiment zu Fuß:Formed 31.3.1897 through the transfer of fully formed companies and officially named the following day as

|

The addition of a third battalion for each of the above regiments was a lengthy process which in some cases was not completed until 1913. They received their 3rd battalions according to the following cabinet orders:

A.K.O. of the 1st April 1903: Regiments 146 and 150

A.K.O. of the 1st June 1906: Regiments 147 and 151

A.K.O. of the 17th May 1907: Regiment 172

A.K.O. of the 4th April 1909: Regiments 165 and 171

A.K.O. of the 29th June 1912: Regiments 148, 149, 155, 160, 161, 163, 166, 173 – 176

A.K.O. of the 4th May 1913: 5. Garde-Regiment zu Fuß, Garde-Grenadier-Regiment Nr.5 and Regiments 152 – 154, 156 – 159, 162, 164, 167 – 170

The all highest cabinet order of the 1st of April 1899 authorised the formation of the XVIII. army corps at Frankfurt am Main. The XIX. army corps (2nd Royal Saxon) was formed the same day. A further two corps were formed on the 1st October 1912 – the XX. at Allenstein in East Prussia and the XXI. at Saarbrücken.

The XX. Armee-Korps received the following regiments: 18, 59, 146, 147, 148, 150, 151 & 152.

The XXI. Armee-Korps: Regiments 17, 60, 70, 97, 137, 138, 166 & 174.

Since 1871 the following non Prussian contingent regiments had been formed (excluding Bavaria):

| 9.Württembergisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.127 | 1.4.1897 |

| Königl. Sächsisches 9.Infanterie-Regiment Nr.133 | 1.4.1881 |

| 10.Königlich Sächsisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.134 | 1.4.1881 |

| 11.Königlich Sächsisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.139 | 1.4.1897 |

| Königl. Sächsisches 12.Infanterie-Regiment Nr.177 | 1.4.1897 |

| 13.Königlich Sächsisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.178 | 1.4.1897 |

| 14.Königlich Sächsisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.179 | 1.4.1897 |

| 10.Königl. Württembergisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.180 | 1.4.1897 |

| Königl. Sächsisches 15.Infanterie-Regiment Nr.181 | 1.4.1900 |

| 16.Königlich Sächsisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.182 | 1.10.1912 |

In accordance with the cabinet order of 1st October 1911 the following infantry regiments received a machine- gun company as 13.company:

1. and 2. – 5. Garde-Rgt., Elisabeth, Augusta Garde-Grenadier-Rgt., Garde-Füsilier-Rgt. and the following line grenadier and infantry regiments: 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 12, 13, 15, 17, 21, 22, 24, 27, 31 – 36, 38, 39, 41, 47, 48, 49, 51, 53, 56, 58, 59,63, 65, 66, 68 – 72, 74, 75, 77, 79, 80, 83, 86, 88, 91, 94, 97, 98, 129, 130, 132, 135, 143, 144, 145, 148, 149, 150, 155, 157, 161, 162, 166, 171, 173 & 176

In accordance with the cabinet order of 1st October 1912 the following regiments received their 3. Battalions: Regiments 148, 149, 155, 160, 161, 163, 173, 174, 175, 176.

The cabinet order of 4th May 1913 authorised the formation of a machine gun company for those regiments still without one on the establishment and a 3. Battalion for the 5.Garde-Rgt. zu Fuß, 5. Garde-Grenadier- Regiment as well as infantry regiments 152, 153, 154, 156 – 159, 162, 164, 167 so that all regiments numbered within the Prussian series now had a third battalion.

Additionally at the 1st October 1913 15 fortress machine-gun companies (Festungs-M.G.-Abteilung) were added as the 14. company of the following regiments and attached to battalions as follows:

| 1.= | F./Gren.-Rgt. Nr.1 |

| 2.= | III./Inf.-Rgt. Nr.147 |

| 3.= | I./ Inf.-Rgt. Nr.141 |

| 4.= | II./ Inf.-Rgt. Nr.129 |

| 5.= | III./ Inf.-Rgt. Nr.21 |

| 6.= | III./ Inf.-Rgt. Nr.47 |

| 7.= | I./ Inf.-Rgt. Nr.65 |

| 8.= | III./ Inf.-Rgt. Nr.88 |

| 9.= | II./ Inf.-Rgt. Nr.132 |

| 10.= | III./ Inf.-Rgt. Nr.143 |

| 11.= | I./ Inf.-Rgt. Nr.135 |

| 12.= | II./ Inf.-Rgt. Nr.130 |

| 13.= | II./Königs- Inf.-Rgt. Nr.145 |

| 14.= | II./ Inf.-Rgt. Nr.98 |

| 15.= | I./ Inf.-Rgt. Nr.144 |

The fortress machine companies were the last peace-time additions to the German infantry prior to the outbreak of hostilities in 1914 and were only raised in Prussia. All formations created thereafter were termed “Kriegsformationen” (war formations) and were disbanded almost immediately after the armistice in 1918.

PRUSSIAN JÄGER BATTALIONS

Already in existence in 1871 were 16 Jäger battalions consisting of the Guard Jäger and Guard Schützen battalions plus 14 line Jäger battalions including two Saxon (Nr. 12 & 13) and one from Mecklemburg-Schwerin (Nr. 14). The Jäger battalion was initially organised into 4 companies (1. – 4.) and as at the 1st October 1913 each received a machine gun company and a cycle company (5. & 6.) respectively. A further Saxon battalion was formed on the 1st April 1887. This battalion

was 3.Jäger-Bataillon Nr.15. This battalion was converted on 1st April 1900 to become Königl. Sächsisches 15.Infanterie-Regiment Nr.181.

BAVARIAN INFANTRY REGIMENTS

Bavaria being the largest of the Southern States retained a certain amount of autonomy regarding its military forces and its troops were organised in separate Bavarian corps, initially of which there were two, increased by the addition of a 3rd on 1stApril 1900. At the formation of the Second Reich, the Bavarian infantry stood at a strength of One life regiment and fifteen line infantry regiments each with three battalions of four companies each. Additionally Bavaria possessed at this time 10 Jäger battalions, which for the most part were used as the basis for a further increase in the number of line infantry regiments.

The year 1872 saw the introduction of new rank designations for the personnel of the Bavarian infantry and Jäger battalions followed in 1873 with the introduction of Prussian badges of rank to correspond with those in use in Prussia:

| Prussian title | Bavarian title |

| Oberleutnant | Premier-Leutnant |

| Unterleutnant | Sekonde-Leutnant |

| Oberjäger* | Feldwebel |

| Sekondjäger* | Sergeant |

| Korporal* | Oberjäger |

| Korporal | Unteroffizier |

*Jäger battalions

As ordered on the 24th July 1878, the formation of two new infantry regiments was authorised from six existing Jäger battalions. 16.Infanterie-Regiment was formed from Jäger battalions 2, 7 and 9 and 17.Infanterie-Regiment was formed from Jäger battalions 6, 8 and 10. A third new Infantry regiment was ordered on the 1st April 1881. The 18.Infanterie-Regiment was formed as follows:

| I.Bataillon | One company each from 1., 4., 12. and 6. infantry regiments as 1.-4. company. |

| II.Bataillon | One company each from 5., 9., 14. and 8. infantry regiments as 5.-8. company. |

| III.Bataillon | One company each from 13., 15., 17. and 7. infantry regiments as 9.-12. company. |

15 July 1890 saw the order issued for the foundation of 19.Infanterie-Regiment which was formed as follows:

| I.Bataillon | One company each from 6., 7., 14. and 5. infantry regiments as 1.-4. company. |

| II.Bataillon | Formed from Jäger battalion 2. |

| III.Bataillon | Formed from Jäger battalion 4. |

In a similar fashion to that ordered by the prussian cabinet order of 11th August 1893, the Bavarian War Ministry issued an order dated 19th August 1893 authorising the formation of a fourth half-battalion for each of the then extant infantry regiments to include the Infanterie-Leib-Regiment. These fourth half-battalions were each composed of two companies (13. and 14.)and were co-located with their parent regimental staff.

These twenty half battalions were soon utilised as ordered by various decrees from 28 June 1896, 20/24 September and 24/28 November 1896, effective 1 April 1897 to form four further infantry regiments with staffs (20. – 23.) as follows:

20.-Infanterie-Regiment

21.-Infanterie-Regiment

22.-Infanterie-Regiment

23.-Infanterie-Regiment

Although I have yet to find the order establishing 13. Machine gun companies for the Bavarian infantry, one can probably assume that in line with Prussia, they were organised in 1911.

BAVARIAN JÄGER BATTALIONS

As previously stated, 10 Jäger battalions were in existence at the start of this period, numbered 1. -10.

With the expansion of the line infantry in July 1878, the following Jäger battalions were converted to normal line infantry battalions:

| 2.Jäger-Bataillon | I./16 | |

| 6.Jäger-Bataillon | I./17 | |

| 7.Jäger-Bataillon | II./16 | |

| 8.Jäger-Bataillon | II./17 | |

| 9.Jäger-Bataillon | III./16 | |

| 10.Jäger-Bataillon | III./17 |

5.Jäger-Bataillon was renamed as 2.Jäger-Bataillon and the strength of the Jäger arm at this time was now:

1.Jäger-Bataillon

2.Jäger-Bataillon (Previously 5.Jäger)

3.Jäger-Bataillon

4.Jäger-Bataillon

On 15 July 1890 2. and 4. Jäger-Bataillonen were converted to rifle battalions in the newly organised 19. Infantry regiment and consequently 3. Jäger-Bataillon was renamed 2.Jäger-Bataillon.

In 1914 therefore the two remaining regular Jäger-Bataillonen were:

1.Jäger-Bataillon König (I.AK., 1.Div., 2.Inf.-Brig.)

2.Jäger-Bataillon (II.AK., 4.Div., 7.Inf.-Brig.)

Following the cabinet order of the 26th March effective 1st October 1901 five independent machine gun detachments were formed. These company sized organisations were built as one guard and four line detachments. Following the cabinet order of 20th March 1902, a further guard and a further five line detachments were formed on the 1st October 1902. A further Maschingewehr-Abteilung; Nr.11 was formed on 1st October 1904.

A Bavarian detachment was formed on 1st October 1902 and a Saxon detachment on 1st October 1903.

Through the cabinet order of 28th May 1913 and effective by 1st October of that year, detachments 6 and 9 were converted to infantry companies as were detachments 1 and 3 following the cabinet order of 4th May 1913. Consequently, detachments 8, 10 and 11 were re-numbered 1, 3 and 6.

The final peacetime strength of the Maschinengewehr-Abteilungen was therefore:

| Garde-Maschinengewehr-Abteilung Nr.1 | attached to Garde-Jäger-Bat. |

| Garde-Maschinengewehr-Abteilung Nr.2. | attached to II./Garde-Gren.-Regt. Nr.4 |

| Maschingewehr-Abteilung Nr.1 | attached to I./I.R.51 |

| Maschingewehr-Abteilung Nr.2 | attached to III./I.R.29 |

| Maschingewehr-Abteilung Nr.3 | attached to I./I.R.97 |

| Maschingewehr-Abteilung Nr.4 | attached to I./I.R.21 |

| Maschingewehr-Abteilung Nr.5 | attached to III./I.R.45 |

| Maschingewehr-Abteilung Nr.6 | attached to I./I.R.67 |

| Maschingewehr-Abteilung Nr.7 | attached to I./I.R.158 |

| Kgl. Sächs.Maschinengewehr-Abteilung Nr.8 | attached to I.R.107 |

| Kgl. Bayr. 1.Maschinengewehr-Abteilung | attached to Kgl. Bayr. I.R. 18 |

Consequently the all up strength of the regular peacetime German Infantry in August 1914 was as follows:

| Garde: | 1.-5. Garde-Regt.z.F., Garde-Gren.1-5, Garde-Füs.Regt. |

| Line: | Inf.-Regt. 1 -182. (Gren.1-12, Inf.-Regt.13-32, Füs.-Regt.33-40, Inf.-Regt.41-72, Füs.-Regt.73, Inf.-Regt.74-79, Füs.-Regt.80, Inf.-Regt.81-85, Füs.-Regt.86, Inf.-Regt.87-88, Gren.-Regt.89, Füs.-Regt.90, Inf.-Regt.91-99, Gren.-Regt.100-101, Inf.-Regt.102-107, Schützen-(Füs.-)Regt.108, Gren.-Regt.109-110, Inf.-Regt.111-114, Leib-G.Inf.-Regt.115, Inf.-Regt.116-118, Gren.-Regt.119, Inf.-Regt.120-121, Füs.-Regt.122, Gren.-Regt.123, Inf.-Regt.124-182). Lehr-Inf.Batl., Stamm-Batl. der Infanterie-Schießschule, |

| Jäger: | G.Jäger-Batl., G.Sch.-Batl., Jäger-Batl. 1-14 |

| Bavaria: : | Inf.Leib-Regt., 1.-23.Inf.Regt., 1., 2.Jäger-Batl. |

In total 217 active infantry regiments and 18 Jäger battalions plus 11 independent machine gun detachments.

Sources:

- Deutsche Infanterie “Das Ehrenmal der Vorderstenfront”. Edited by v. Eisenbart Rothe, Tschischwitz and Beckmann. Published by Verlag Berhard Sporn, Zeulenroda in Thüringen 1933.

- Deutschlands Heere bis 1918 by Günther Voigt, Biblio Verlag, Osnabrück 1980.

- Formationsgeschichte des Deutschen Heeres 1815-1939 by G. Wegner. Published by Biblio Verlag, Osnabrück 1992.

- Formations-und Uniformierungsgeschichte des preußischen Heeres 1808 bis 1914 Volume 1 by Paul Pietsch. Published by Verlag: Helmut Gerhard Schulz, Hamburg 1963.

- Führer durch Heer und Flotte 1914 by B. Friedag. Reprint of the 1913 edition published by Biblio Verlag, Osnabrück 1993.

- German Infantry 1914-1918 by David Nash. Published by Almark Publications 1971.

- Organisation, Bekleidung, Ausrüstung und Bewaffnung der Königlich Bayerischen Armee von 1808 bis 1906 by Karl Müller. Reprint of the 1906 edition published by LTR-Verlag, Buchholz-Sprötze 1996.

- Ruhmeshalle unsere alten Armee by Dr. Martin Lezius and others. Published by Militär Verlag Leipzig ca. 1930.

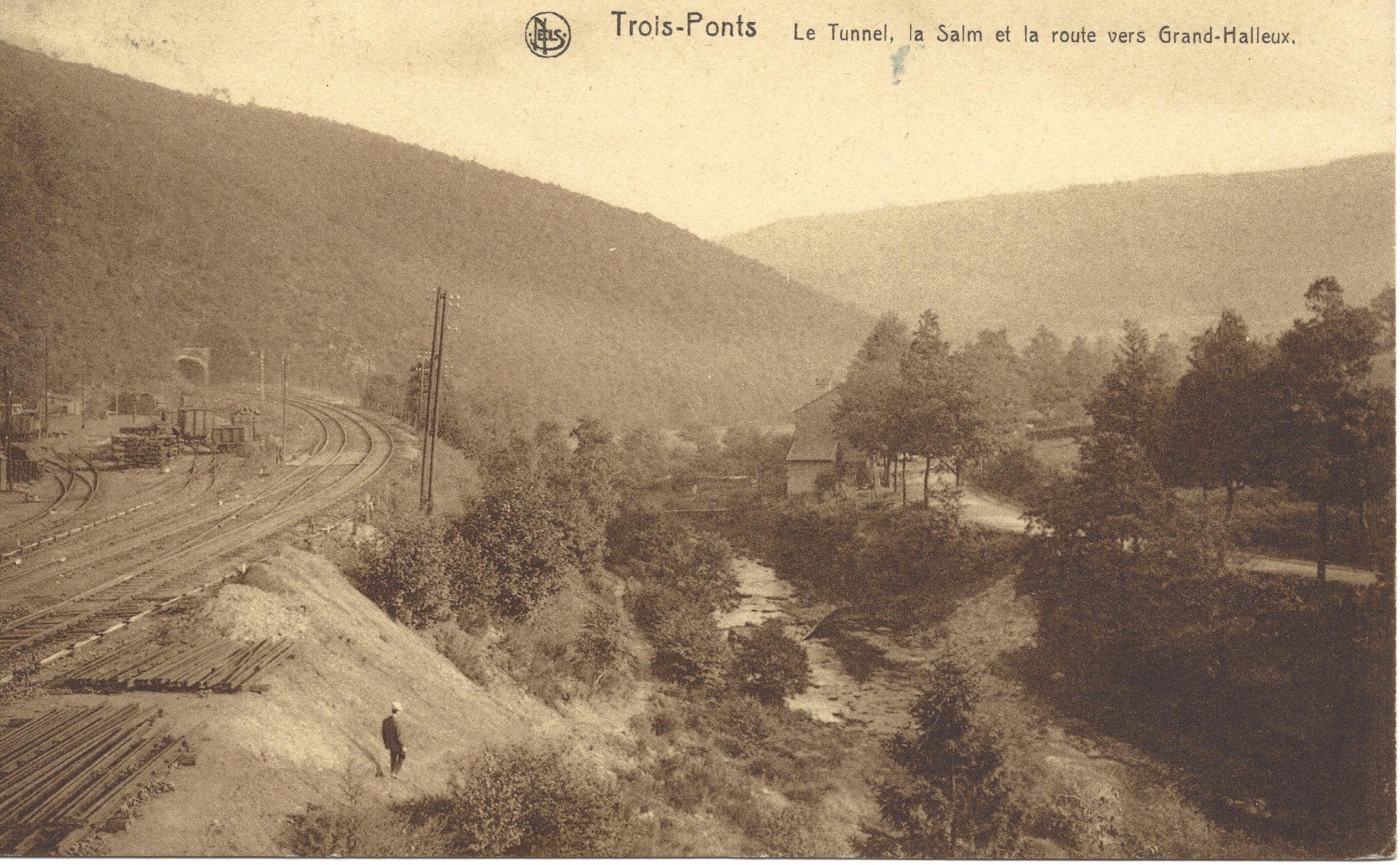

Look at this picture. When one thinks of the invasion of Belgium we think a wide open plains. Easy terrain for both cavalry and infantry. No hills. Some rivers. But looking at the picture of the 30 or so kilometers between the German border and the fortress at Liège you can see that this is pretty rough country. This terrain had to be covered before anybody started attacking any forts in Liège. In addition, and more importantly, the railroads leading from the homeland through Liège had to be open and free to move along with large amounts of supplies. Supplying the German army was a function of railroads cars. Therefore, we would expect that the Great General Staff of the German army would ensure that their plan included clearing these railroads. But that part of the plan proved to be too tough of a nut to crack. So the Germans kind of ignored it and hoped for the best. This alone should be reason to run out and purchase the book.

Look at this picture. When one thinks of the invasion of Belgium we think a wide open plains. Easy terrain for both cavalry and infantry. No hills. Some rivers. But looking at the picture of the 30 or so kilometers between the German border and the fortress at Liège you can see that this is pretty rough country. This terrain had to be covered before anybody started attacking any forts in Liège. In addition, and more importantly, the railroads leading from the homeland through Liège had to be open and free to move along with large amounts of supplies. Supplying the German army was a function of railroads cars. Therefore, we would expect that the Great General Staff of the German army would ensure that their plan included clearing these railroads. But that part of the plan proved to be too tough of a nut to crack. So the Germans kind of ignored it and hoped for the best. This alone should be reason to run out and purchase the book.

In this rough terrain along the railroads were four tunnels that the railroads ran through. If the tunnels were not there the Germans would not have any choice but to build a bypass which could take months. So the Germans in the original Handstreich plan sent cavalry squadrons to secure the tunnels. Yes that’s right. The only plan was to assume that there would be no enemy resistance and send a few horsemen galloping many kilometers to secure this absolutely crucial point.

The Belgians were not stupid. They planned on dynamiting these tunnels prophylactically. While all four tunnels were rigged with explosives, they had serious problems with the age of those explosives and their vitality. Only one tunnel was permanently blocked through the use of these explosives. This picture shows the Trois-Ponts Tunnel.The plan was to create an obstacle in its middle. Six of the eight charges detonated caused an obstruction such that on August 11 the Germans started constructing a bypass track. They finished on August 30. Meanwhile, trains stopped on one side of the tunnel, and their cargo transshipped. German accounts said that on August 11 the line was cleared up to the tunnel of Trois-Ponts but with a break of forty-two meters in the middle it would take months to reopen. In consequence, the Germans then opted for a 1.75-kilometer bypass to span the River Salm, building a 120-meter long and twelve-meter high wooden bridge. That work lasted until August 28.

After that tunnel repair was entrusted to a private German company, Grün und Bilinger, which started work on August 30 and cleared the passage on one track by November 26. In early 1915, the Germans decided to rebuild the tunnel for two tracks while maintaining traffic on a single track. That work ended in December 1915.