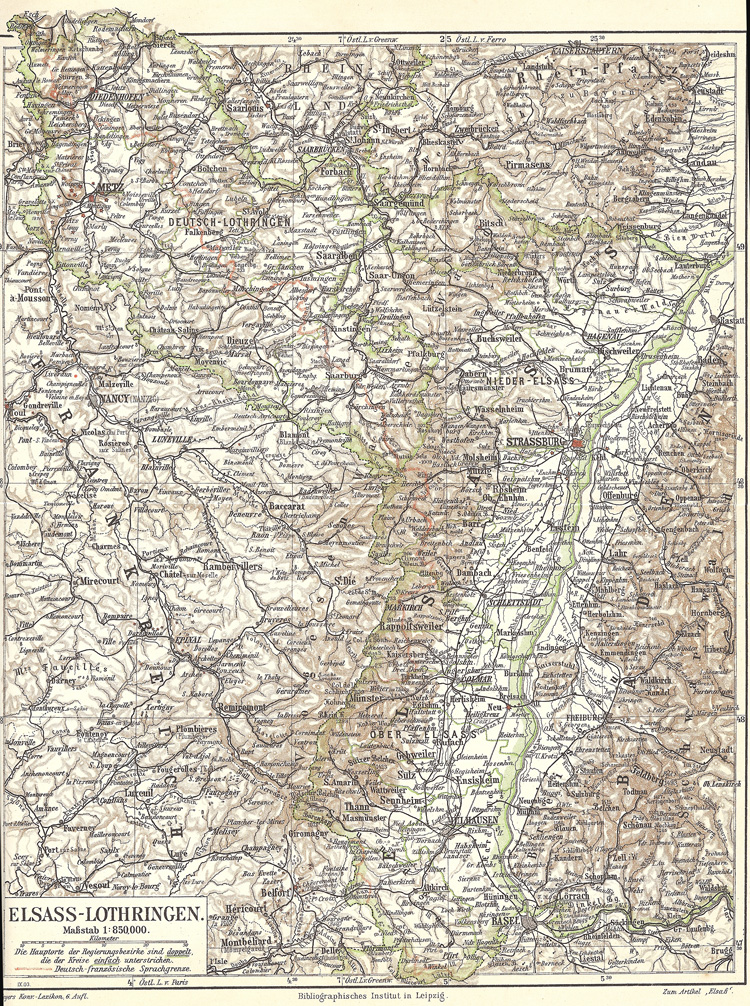

(Elsaß-Lothringen)

This territory, also known as the Reichslande, was a prize seized from France after the Franco-Prussian war of 1871. It was a Reich’s province until it became a quasi-state in 1911. It never was an actual state of the Imperial German Empire. The Kaiser appointed the head administrator , who was called the Reichsstatthalter. The province was split into three sections: upper Alsace (which was the most southern), lower Alsace that was the more northern, and Lorraine, which included the fortress city of Metz. Lorraine was the most culturally French of the areas and it was the primary language. The majority of the population did speak some German or an Alsatian dialect of German. Historically and realistically, there was no Alsace-Lorraine prior to the Franco-Prussian War. The first myth to expose is that there was no such thing as an Alsace-Lorrainer. There was Alsace, and there was Lorraine and they were joined for political expediency. The populations were not homogeneous. Alsace often held sway over Lorraine due to the immigration of German middle classes into Alsace.

There were problems with this area from a constitutional perspective. The peace treaty of 1871 ceded all of France’s rights to title and territory of Alsace-Lorraine to the German Empire, but the imperial constitution made no provision for the disposition and administration of such a territory. The imperial constitution assumed that between the individual territories and the imperial power, a state power was interposed to execute many laws and functions. This was no state. The attempted solution was to make the Kaiser the head of state for Alsace-Lorraine and to make it an imperial territory. The Statthalter or imperial deputy was appointed by the Kaiser and his personal representative. The powers of the Statthalter were attached to the person not to the office. Prior to statehood, there was an emasculated territorial committee in place of a parliament. They had 15 representatives in the Reichstag, but zero in the Bundesrat.

There was much outcry and confusion about citizenship immediately after unification, when Alsace-Lorraine moved from French control to Imperial German control. The residents of Alsace-Lorraine were given the option to maintain French citizenship, but they had to declare their intent and to move to French territory by 1 October 1872. Those who did not leave were automatically granted German citizenship. There was a group of 100,000, called the optants, who had declared their intent to leave, but for various reasons did not. This group fell through the cracks creating 100,000 individuals who had no citizenship. Many minors returned to France to avoid service in the imperial German military. Forty-five percent of the French Foreign Legion between 1882 and 1908 originally were from Alsace-Lorraine. It is estimated that in the first 15 years of German rule, 156,000 individuals left the Reichslande for France. As French citizens moved out, imperial German citizens from many states moved in. Many of these German citizens took jobs as civil servants for the empire in Alsace-Lorraine. By 1910, twelve percent of the population was Germans, who had immigrated into the Reichslande. This was more prominent in the larger cities where between 30 and 41 percent of the population was immigrant Germans.

In American terms, this was Indian country. There was an eternal dilemma facing the Germans—should they govern Alsace-Lorraine as a conquered territory for national security purposes or should they integrate Alsace-Lorraine into the Imperial German Empire. The Germans, who thought originally that Alsatians would welcome them as long-lost German brothers, found many parts of the population to be pretty much anti-German. Many aristocratic authorities and especially the military considered all people from Alsace-Lorraine to be highly untrustworthy and called them Wackes. Draft evasion was a telling metric. In 1872, twenty thousand out of 32,000 draftees failed to appear. By 1879 this had dropped to 25 percent and by 1904 to ten percent. It is impossible to apply one homogeneous view of resistance to service in the Prussian military. Much of it was economic, some religious. There was an urban/rural divide as well as a native/German immigrant divide, yet some native inhabitants of Alsace and Lorraine even embraced Germany. Many Germans came to view the Alsatians and those from Lorraine as disloyal Germans.

Another myth is that the German government used a repressive program of coercion to impose their will on people from Alsace-Lorraine. In fact, there was a huge amount of vacillation and the Empire never decided whether coercion or conciliation with the right tool. There was a reasonable chance of German success and integration of the province into the German Empire until the Zabern affair of 1913 — 1914.

In May 1911, the rules were changed for Alsace-Lorraine as it moved closer to statehood. There was a constitution, but it was not a state. Many historians overlook this fact. The Landtag for Alsace-Lorraine was to consist of two houses. In the upper house of 36 members, one-half was appointed by the Kaiser. Others were members by virtue of holding certain offices. The lower house had 60 members elected by secret ballot based on universal suffrage. Laws were made by these two chambers and the Kaiser had an absolute veto. Alsace-Lorraine was represented in the Bundesrat by three votes but they would not be counted if they provided a majority for Prussia; and the territory elected 15 members to the Reichstag but these were not allowed to vote on issues concerning the Reichslande.

Another event along the same line that tested the German imperial system and made it incredibly clear that Alsace-Lorraine was a second-class part of imperial territory was Zabern 1913. Zabern was a garrison town of 9000, mostly Catholics, in lower Alsace that had since 1890 housed the mostly Lutheran 99th Infantry Regiment. The major protagonist was 20-year old Lieutenant Günther Freiherr von Forstner who had been educated at the upper Prussian cadet school. While he retained airs of aristocratic privilege, the townspeople thought of him as a buffoon. He made disparaging remarks about his recruits from Alsace-Lorraine and the French Foreign Legion. He referred to the local population as “Wackes.” The claim is that during his instruction hour he had offered his recruits 10 marks instead of three months in prison, should they stab a rowdy “Wackes.” The paper published this incident and soon mobs threatened Lieutenant Freiherr von Forstner. The commander of the 99th Infantry Regiment and the burgomaster got involved unsuccessfully and the fire brigade was ordered to drive off the crowd with hoses, which they did neither enthusiastically, nor successfully. A company of soldiers from the garrison arrived on the scene and arrested those who refused to leave.

Lieutenant Freiherr von Forstner was reprimanded, but on the very next day, he and several other officers had an alcohol-induced altercation with some local youths, and one of the officers, a Lieutenant Schad, called out the guard with fixed bayonets. This situation continued to simmer until 29 November when the same Baron Forstner went shopping for chocolates with four armed soldiers. Some of the locals made fun of him and the same Lieutenant Schad started arresting locals. The regimental commander, Col. von Reuter, deployed 60 men and ordered them to load rifles and barked commands with drums beating.

Baron Forstner was transferred to Infantry Regiment 14, in which he was killed in action on the Eastern Front in 1915. Schad was transferred to Fusilier Regiment 85 and while he survived the war, he was not promoted beyond Oberleutnant.

The key issues revolved around the rights of the locals versus the rights of the army. Did the army have the right to act as police in arresting citizens and quelling unrest? Who had the right to discipline members of the army? Should the local authorities and local courts have jurisdiction? Could the Kaiser and the army maintain their personal authority in this matter? As it turned out, the army whitewashed and sidestepped the constitutional question. The residents of the Reichslande learned without question that their constitution had little value. While the war interrupted the outcome of this incident, it certainly exposed nerves.

The capital was Strassburg, i.e. the 24th largest city in the empire, multicultural and bilingual. Catholics outnumbered Protestants 1.5 million vs. 400,000. The old French regime had given the Catholic clergy significant power. Total population in 1914 was approximately 1,900,000.

(Silverman, 1972) pg. 6-8

However, the railroad was not included and was eventually purchased by Germany.

(Silverman, 1972) pg. 36-64

(Silverman, 1972) pg. 65-69

(Silverman, 1972) pg. 1-3

(Silverman, 1972) pg 144-147

„Wackes“was a very bad slang word derived from “vagabond” and suggesting that all “native” people in Alsace and Lorraine would be little more than begging and stealing “underclass” proletarians.

(Blackbourn, 2003) pg. 285-286

(Kaiserliches Statistisches Amt, 1914)