George Wylie and Joe Robinson

20 March 2009

There are lots and lots of confusing pictures about Landsturm. This is easily traced to the fact that most people do not understand the Landsturm and that there was no real standardization. With the exception of a paper drill, before World War I they did not exist. They existed only on paper.

In the Wehrordnung of 1888 the Landsturm was laid out in two separate and distinct levies or bans. They’re really one along the lines of young boys and old men. Between the first of January and the middle of February, a list of service eligible young men from the subject class year was put together. Requests for exemption from service were considered by the lowest recruiting committee. Citizens were categorized by class designated by the year in which they were born. So the class of 1892 for instance would be the recruiting process in 1912 at the age of 20. This is often confused because the French system used the year in which they reported in as a class number or year. There were basically two divisions of manpower, active military service (Dienstplicht and Landwehr) being one; and the Landsturm being number two. In certain theory, this was supposed to cover the ages of 17 through 45.

Most guys got out of Volksschule at the age of 14. Required active service started at the age of 20. Between the ages of 17 and 20 you were not part of the Dienstplicht. You actually were assigned to the Landsturm, ban 1. So going back to our example the class of 1892 would enter Landsturm ban 1 at the age of 17 or in 1909. The entire class – really almost everyone was entered on the rolls of Landsturm ban 1. These individuals had no military training, were not organized into standing units, and were really there for reporting purposes.

The first ban included all untrained folks that were not on Dienstplicht from the ages of 17 through 39. There were individual exceptions based upon officer and noncommissioned officer training and a few folks who enlisted or were in the one-year volunteer program.

During the year the class turned 20 there was a large local event known as the Musterung. The ritual Musterung was supposed to announce the class into the military – Dienstplicht. Reality was different as not nearly all of the individuals entered Dienstplicht. Not everybody served. Look at this table from 1907.

Number of men liable 556,772.

Physically unqualified 35,802.

Voluntarily enlisted before required age 57,739.

Sent to Navy 10,374.

Available as army recruits 452,857.

Assigned to active military service 212, 661.

Assigned to Landsturm 240,196.

While the top line continued to grow, the percentage of soldiers needed varied by year’s requirements for replacements and maneuvers. The population had grown from 56 million to 67 million from the turn-of-the-century to 1913. Yet in 1912, only 240,000 were assigned to active military service, and in 1913, 304,000 were assigned to active military service.

The second ban of the Landsturm included all soldiers and untrained individuals between the ages of 39 and 45. Second Ban Landwehr soldiers joined the second ban of the Landsturm at age 39. This was a really rough militia. There was no training requirement. A home guard at best. This was the way individuals were controlled throughout their lifetimes. Not only were the reserve and Landwehr controlled by the Bezirkskommandos the Landsturm was controlled by the Army Corps District in the same way – Bezirkskommando. Administratively Landsturm soldiers were grouped by town and the lowest recruiting organization.

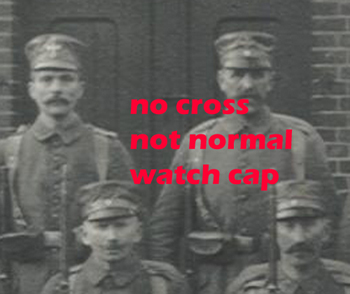

At the age of 45 the class would be mustered out as in the picture below. Note the lack of uniforms. There was a great deal of pressure to get Landsturm soldiers to join the veterans organization and be put in the “reliable” group of citizens.

War 1914

When war was declared the Landsturm ran towards the colors. Those with military training were formed into battalions. Below are Bavarians from Landsturm Btn. Rosenheim (3rd Btn.), and are identified as such by the words on their white armbands. This photo was sent from Munchen on 8 Sept. 1914, 1 week after mobilization. The guy kneeling with the shooting award is also wearing a “Kaiser Centenary” medal, as well as another ribbon in his left top button hole. Note the lack of any metallic collar devices, but there is a metallic Arabic number one on the shoulder straps for I Bavarian A.K.

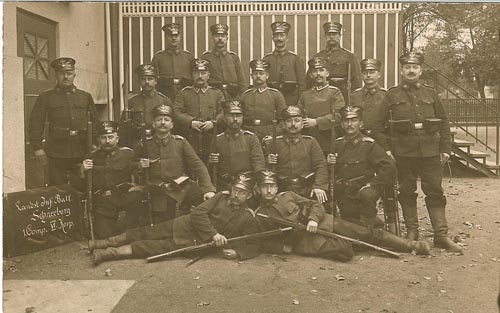

These battalions vary greatly and standardization was not found anywhere. The people with military training came from ban two and the organization was formed into battalions named after the town such as:

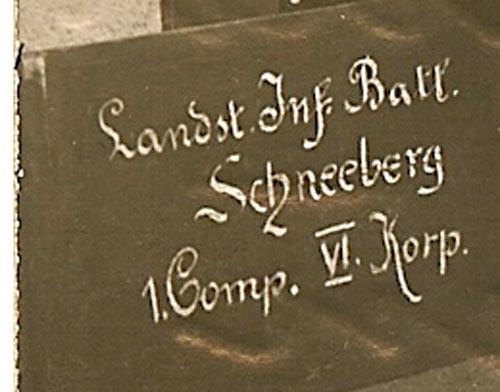

Ldst.- I.-Btl.-Schneeberg .

There were 334 Landsturm battalions established. Of these 142 were considered “mobile”. Most of the Landsturm were placed towards the Eastern front and eventually they were used in the area of communication to replace Landwehr soldiers. There was even some use of Landsturm on the Western front in quiet sectors.

The battalions that fell under the Bezirkskommandos were administratively grouped into brigades that followed the peacetime brigade boundaries of the Army Corps District. So as far as the number of battalions per brigade — it varied greatly. Determining factor was how many battalions were located inside the geographic boundaries of the brigade area. This brigade assignment can be easily seen in pictures as the individuals wore 25mm metallic Arabic numerals or “Collar Dogs” to display brigade affiliation as these from the 89th,43rd & 5th Brigades. This was an administrative brigade number. This did not reflect an employment capability.

Landsturm brigade organization is really a bit of a misnomer. There was no brigade for the Landsturm as in a commander and a staff. There were administratively grouped into brigade organizations only because they were administered by the Army Corps District which was itself broken down into brigades. It gets even a little more foggy because the battalions were administered through the Bezirkskommando. This is the same as a Landwehr soldier. Some battalions did not fall under a Landwehr Bezirkskommando. There was such an organization as a “Landwehr inspection” which took the place of a Bezirkskommando in some instances. I do not believe that these individuals wore any kind of collar dog.

Those Landsturm units that were used in the opening order of battle were often placed into Mixed Landwehr Brigades. This did not follow perhaps any logic at all. For example the first and second Landsturm infantry battalions of the XVII Army Corps were part of the 70th Mixed Landwehr Brigade which was part of the Landwehr Corps of the 8th Army! The collar dogs did not reflect the number of that brigade.

Putting equipment on these soldiers was a ragtag operation. The Army Corps District had stockpiled some equipment but not nearly enough to handle the influx. Old equipment was heavily utilized for the Landsturm. In many cases Landsturm units that had superior equipment issued had to turn around and surrender that equipment to frontline soldiers.

What constituted a uniform was relatively interesting. The German psyche was built around experiences in the Franco-Prussian war. The great moral dilemma was identifying enemy combatants as opposed to civilian partisans known francs-tireurs. Even this was at times distasteful for the Germans as irregular warfare was not considered quite “right”. Perhaps one quarter of the German troops during the Franco-Prussian war were tied up defending the lines of communication against the francs-tireurs.

The senior German commanders of World War I in 1914 had participated on the German side during the Franco-Prussian war and those memories were deeply emplaced. The Hague convention of 1899 required in article 2 that militias such as the Landsturm or francs-tireurs be under responsible command, have a distinct uniform emblem, carry arms openly, and observe the laws of war. The distinct uniform emblem and following this convention when convenient became a mantra of the German forces and eventually led to many excuses for atrocities.

Note the white armbands utilized in the pictures below. Armbands were often used to indicate a uniform.

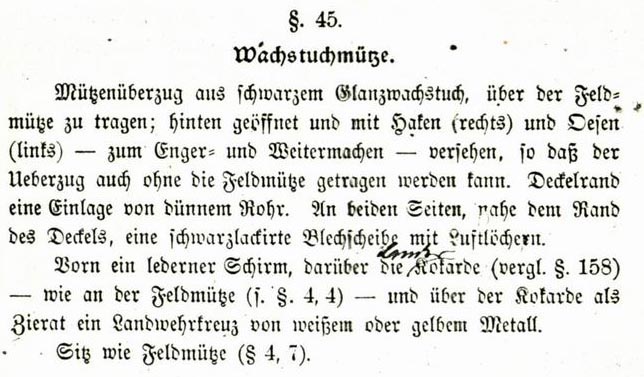

The standard Landsturm headgear was supposed to be an oil cap. This was known as a

Wachstuchmüzte and came in many forms. As you can tell from the regulation below the real intent was to wear the oilskin cap over the Feldmütze.

There was supposed to be a cockade from the land on the bottom and a yellow or white metal Landwehr cross on the top. This did not always happen and there were far fewer oilskin caps than were needed. While many of the caps were indeed from oilskin, some were of cloth. Standardization of the insignia left much to be desired.

This first example is a basic oilskin cap, which has the metallic Landwehr Cross over the Landes or State cockade. Notice the absence of any collar devices. This photo was very early War, he was also wearing an armband with the name of the city / town where his Btn. was raised. Not all crosses were what one usually expected. The Prussian cross had the normal motto. However, Bavaria, Hesse, Saxony, the Hansa cities, and Wurttemberg had unique mottos like the examples below. There also were Fürst crosses. These crosses were sewn on to the oilskin cap or attached by two prongs. For some reason a cross with the date 1914 shows up.

This NCO on the left is wearing a feldgrau cloth type wachstuchmutze also with the Landwehr Cross on top and the Landes cockade on bottom. It retains the black leather visor of the oilskin mutze. The photo is undated & there are no shoulder straps to identify his unit. The individual at center from 41st brigade has a Landes cockade with a Landwehr cross on it, and a national cockade centered above. The fellow at right has both cockades centered above and below the Landwehr Cross. The hat visor appears feldgrau.

His picture is dated April 1915.

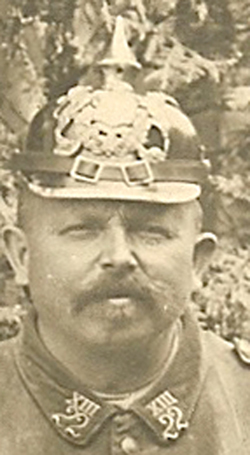

These three hats have a chinstrap which were not common to all caps. This individual on the left was assigned to the 12th brigade. The number 12 on his collar is called a “collar dog”. The one at center displays the upper Reich & lower Landes cockades. His photo was sent from Nordheim / Hannover 4 Sept. 1915. The one on the right has a visor which appears it may be feldgrau. This one has the lower Landes cockcade and the upper Reich cockade is centered & mounted over the Landwehr Cross. This set up is truly uncommon. Photo was undated, and there are no shoulder straps or collar dogs to identify his unit.

The variations on the types of hats seems endless. As the picture below will show you variations in even one unit were significant.

In addition to the wachstuchmutze, there was also an uberzug (cover) to eliminate the nighttime glare from metal devices attached to the hat. The gent at right has a different variant, which does not have a cover over the visor, and seems to use a drawstring to hold it onto the mutze.

Shakos

There were not enough oilskin caps to go around. The first step of substitute headgear was to revert to the old Landwehr shakos. Units just dusted off the old helmets and reissued them.This was not always clean as there was a mix and match in the picture shown below.

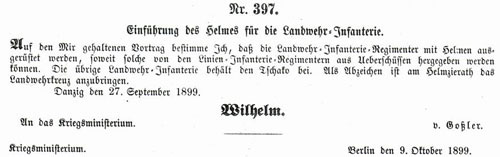

Using old shakos created further standardization problems. Not only were there shortages of oilskin caps but there was a shortage of standardized old Landwehr shakos from earlier than October 1899.

In October 1899 the Landwehr was allowed to wear helmets. However, they were instructed to maintain the shakos. Exactly what this last directive amounted to was probably carried out differently in different areas.

Most shakos were supposed to be leather with a large Landwehr cross and blazoned over the colors of the land. However, all kinds of shakos were pressed into service. Sometimes it is difficult to determine any kind of standardization within a unit as some photographs show old Landwehr shakos mixed in with shakos with Prussian eagles on them. Shakos also became part of the Ersatz world. Not only was there an endeavor to make Landwehr shakos out of filtz but there were also shakos such as this one from the Cotbus Battalion.

Other old shakos existed for the Landsturm including these old Hessian shakos.

Here is a twist. This photo on the left has a sign that reads “Andenken an Russland 1914”. It appears the tschacko, feldzeichen , wappen & chin strap were painted feldgrau. If you look at the upper part of the Landwehr wappen, bottom right of the feldzeichen, you can see some white paint that was chipped or not painted over. There is no explanation for this. Was it on a trail basis or the work of an overzealous commander? In addition to the Landsturm Tschako there was also an uberzug as the 37th Brigade man on the right has.

One cannot jump to the conclusion that shako automatically means a Landsturm soldier or unit. In addition to the many units equipped with more modern shakos the older ones were used for other units also as this ersatz battalion photograph shows.

Corps Collar Dogs

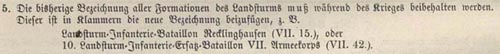

It is very difficult to keep track of individual battalions as their name changed throughout the war and organizational structure was scattered in different directions. In the spring of 1915 the use of corps number and battalion number within that corps became the standard for naming battalions. In our example Ldst.- I.-Btl.-Schneeberg became example Ldst.- I.-Btl.-Schneeberg (XIX. 17). In theory the collar dogs changed at the same time showing a Roman numeral corps number and an Arabic battalion number.

The brigade collar dogs were eliminated on 14 April 1915. There was an AKO that detailed all of the different insignia of the Landsturm.

While this directive was all-encompassing it is not clear how well it was followed or to exactly what chronology. An allowance was specifically made to use up the existing brigade numbers — what ever that meant.

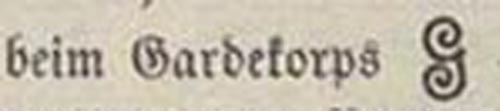

What the AKO did not do is indicate the exact size of the collar dogs. It also did show them to be displayed on top not side by side. It also directed a specific corps symbol to be used for the Guard Corps. While the symbol looks like some sort of a fancy “G”, the actual symbol looked very much like an S.

A series of different collar dogs ensued. New smaller corps numbers were added along with smaller battalion numbers. Old-style big numbers were used in conjunction with the small numbers when they were available and the AKO was followed — sort of. In the picture below this Landsturm on left uses a combination of small corps numbers and large battalion numbers. The individual on the right has small numbers all around and the individual in the center has corps numbers only.

While the contingent elements of the Imperial Army melded into the Prussian corps system, as the soldiers from Württemberg and Saxony above show, Bavaria had their own corps structure. In collar dogs and this was reflected by the letter “B” co-located with a corps number.

Collar dogs that were improperly displayed side-by-side were also displayed in different ways. Some have their battalion number first and some had the corps number first.

Some of the units displayed combinations and often times no collar dog was displayed at all.

Spiked Helmets

Spiked helmets were issued to Landsturm soldiers as the helmets became available in early 1915. As with most things regarding the Landsturm there were exceptions to the rule as the photo of the 44th Brigade Nieder Zwehrin Btn.below confirms.

The Landsturm helmet cover or Uberzug (M1892) was issued after 2 March 1915. The Uberzug was directed to have a green Landwehr cross and battalion number underneath. This was accomplished by sewn on felt or cloth, or use of stencils. As you can see from the picture below the individual at the left has a battalion number on his collar dog but no battalion number on his helmet.

As with all Landsturm regulations the guidance was followed somewhat. The endeavor to identify the Landsturm soldiers from a distance was codified by the large Landsturm AKO on 14 April 1915. A large Landwehr cross and bn. number in arabic were authorized. There are many variations on the Uberzug identification. The individual on the left correctly displays a corps number and a battalion number on his collar and the Landwehr cross and battalion number on his Uberzug. The individual in the middle has a blank Uberzug. The soldier on the right uses a metal Landwehr cross from an oilskin cap on his Uberzug.

The forlorn individual on the left below has a combination with a Landwehr cross corps number and battalion number all on the Uberzug. He only has the corps number on his collar dog. The individual in the middle has complete information on his collar dogs but there is no Landwehr cross on his Uberzug. The individual on the right has the Landwehr cross corps and battalion numbers on his Uberzug but it is displayed vertically. He has guard Litzen and not collar dogs and there is no real explanation of this.

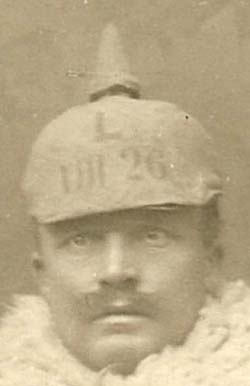

Finally this picture shows a soldier of XIII 26 but his Uberzug has the letter “L” which was used not for Landsturm but by AKO only for the Landwehr!

As mentioned above, the Landsturm Uberzug was directed to have a green Landwehr cross with battalion number underneath, as the III Armee Korps man on the left from the 11th Btn. illustrates. The Landwehr Cross and Btn. number are sewn on. The M1915 Uberzug was issued 28 June 1915, at the same time that initial issue of the M1915 pickelhaube occured. This uberzug had a removable spike cover, and had slits on the sides that allowed the chinstrap to be passed through the cover. An AKO of 21 September 1915 required all helmet tops to be the bayonet style, and all troops at or near the front were ordered to remove their spikes, as the III A.K. 50 Landsturm Btn. soldier in the center illustrates. On 27 Oct. 1916 all troops were ordered to remove all unit Identifiers & numerals from all Uberzugen, as this man from XIX A.K. 20 Btn. — Ldst.-1st Btl. Rochlitz formed August 1915 on the right illustrates.

Men of the 3rd Kompanie of Bavarian Landsturm Infantrie Btn.Gunzenhausen, III B.A.K. 6th Btn., sent 29 April 1917 from the “Front”.

Steel Helmets

The first shipment of German steel helmets or stahlhelms arrived at the Western Front for field-testing in December 1915. The first 30,000 helmets were issued to assault troops serving in Verdun at the end of January 1916. 22 January 1916, Gen. Ludendorf, Chief of the General Staff, announced the priority that German troops were to be issued stahlhelms: Infantry, active cavalry, pioneers & mortar units, Foot & field artillery batteries. Chief of Staff of the Field Army, General von Falkenhayn authorizes the introduction of stahlhelms in February of 1916. Helmets were designated Modell 1916.

So it came to pass that Landsturm troops were issued stahlhelms. All German troops Troops with steel helmets were ordered to turn in their pickelhauben to the replacement troops sections 11 Feb 1917.xv Oilskin became rare as the war progressed and in 1918 the oilskin caps were eliminated. Collar dogs became less obvious in photographs.

However, the Landsturm battalions maintained their identity and the last division formed in the war 303 Infantry Division consisted entirely of Landsturm battalions: Landsturm Bns I/25, Bavarian I/25, Bavarian I/26, XI/35, XIX/27, III/50, III/51, XVII/12, XVIII/54 and XX/22. This unit served on the Eastern front. Unfortunately the photo below is undated and the unit is not identified. If you look closely you can see the collar dogs on their tunics.

Landsturm soldiers continued to serve throughout the war. In the West, we tend to think of the Landsturm as operating mostly in quiet sectors, guarding Prisoners of War, used as Occupation & Fortress Troops and rear echelon support truppen who rarely went into combat. This is probably because that was the observations coming from our countrymen who were involved in the conflict on the West Front. But in the Ost Front, Landsturm troops were more heavily relied upon in combat formations. Their contributions to the overall Imperial German War effort are under appreciated and little understood. Some Landsturm battalions were combined into Landsturm regiments. some of those became mixed with other elements such as the Landwehr. Eventually Ersatz regiments merged into guard Regiment and as Cron said: “…the original clear distinction accorded to active status, Reserve, Landwehr etc. had become completely blurred.”

This is a small primer on Landsturm. We welcome your comments and corrections! There are several pictures in this article from the collections of Randy Trawnik and Brian Kostel, we thank them.

PS- as a side note I still find things I have no explanation for. Look at this one. A Landsturm guy with a brigade collar dog and a tropical helmet. Why? The collar dogs like this went out long before there was a Macedonian front.

Notes on the German Army in the War, Translated at the Army War College, Government printing office, Washington, 1917, pg. 28.

Harrell John, L, Regimental Steins, The Old Soldier Press, Hagerstown, MD, 1983.

Berghahn, Volker, Imperial Germany, Berghahn Books, Providence, 1994, pg.43.

It is important to remember that the abbreviation Korp. Stands for Korporalschaft not Army Corps. So this is a small group of trainees organized in a Korporalschaft.

Horne and Kramer, pgs. 140-148.

The only reference I know of that has the Landsturm Battalion identification in is the Busche manuscript. This specific Battalion is located on page 112.

xv Ludwig Baer – The History of the German Steel Helmet 1916–1945

Trawnick Collection