Kit Helmets

Kit Helmets

Joseph P. Robinson.

28 September 2005. May 2018

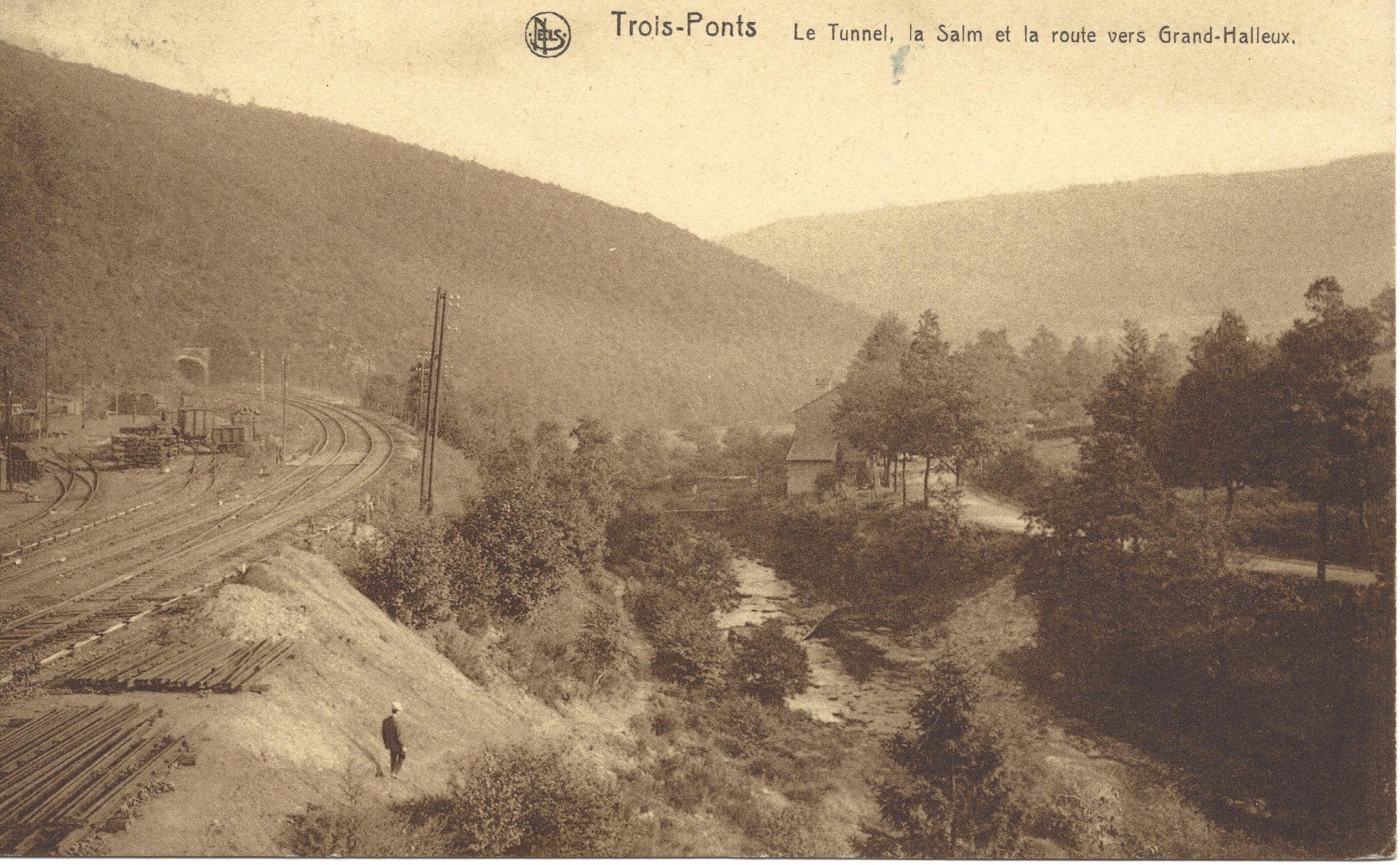

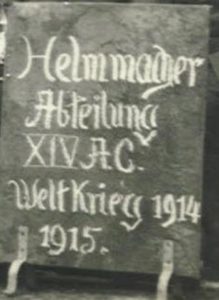

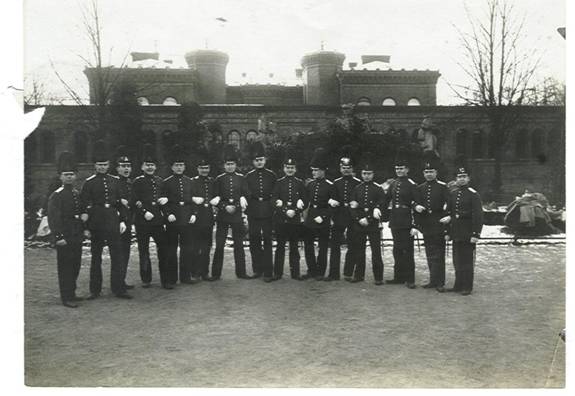

Collectors have spent a lot of time trying to determine how helmets flowed into the units. Several years ago, few collectors understood it at all. But today, serious collectors understand the Bekleidungsamt markings on helmets is the vehicle that let us to study where helmets came from and how they were issued. There are still lots of holes and misunderstanding. Just as you thought, you understood a great deal of it another picture surfaces and throws you a curve ball. This is a series of two pictures that have created great discussions. These pictures were not taken at the same time but in the same place of roughly the same group of people. They were both sent by Heinrich Hölzer. These individuals are from the Helmmacher Abteilung of XIV Corps. XIV Corps was the corps of Baden troops in the Prussian army. The helmets that they are proudly displaying are metal ersatz helmets. For lack of a better description these were “kits”. The helmet shell was factory produced as well as separate front visor, rear visor, liner, spike assembly, rear spine, cockades and chin strap and wappen. These separate components were then “snapped” into place by an assembly organization — by this Helmmacher Abteilung. This unit outlived its purpose with the introduction of the M15 helmet. However, when they were in demand, a man could snap together a helmet fairly easily.

In peacetime, pre-war Germany equipment was issued by Army Corps. Each Corps had a small but very important supply unit called the Bekleidungsamt (BKA). Consider them clothing depots. Pictures of the BKA and the BJA(repair outfit) focus on sewing machines and often times civilian workers. The BKA was not standard in size or organization but varied by Corps and nationality. In some cases civilians populated the “handwerk” section. Prussian Corps had about 75 NCO and OR types while Bavarians had 200. Wurttemberg’s Corps and the two Saxon Corps had 28 NCOs but no ORs each.

The uniforms of the Bekleidungsamt were very specific. These pictures show a mixture of uniforms as was common for recruits. They use the old blue uniforms for training. It looks like some troops behind the lines use these also for daily activities.

The shoulder of strap and sleeve decorations in the pictures seem to match the XIV Corps Bekleidungsamt. This makes immense sense, but the words Helmmacher Abteilung is a new one.

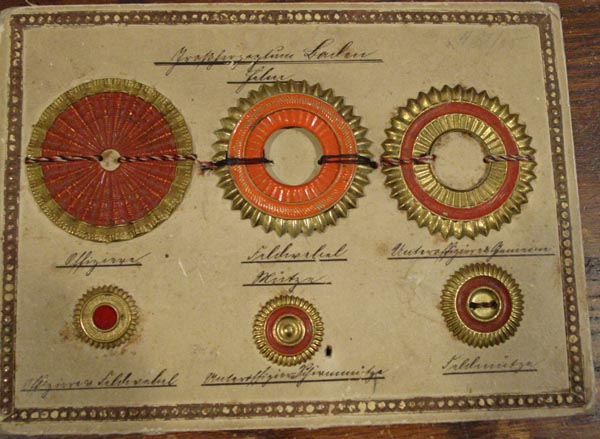

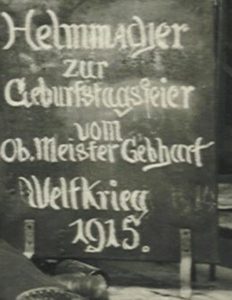

The gentlemen in the second photo were obviously gathered for a birthday party of Head Master Gebhart. (Obermeister translated as “head master” has nothing to do with schools. The term Obermeister denotes the chief craftsman of a guild, usually. He was a respected master craftsman of the region and elected to this office. In this case, though, he will have been the most senior master craftsman of the Abteilung of the Bekleidungsamt or maybe even of the whole Bekleidungsamt.–Klaas Dierks). You can plainly read the cancellation mark of the first of March 1915 in Baden on the other card. You’ll notice that there are both Prussian and Baden wappen on these new helmets. Why? There is a mention of Gren Reg. 110 on one of the cards.

You’ll also notice on the bottom shelf, there are five helmet forms. The center three are liners that have not been dyed. The outer two are shells without the visors attached. These are helmet forms ready to be assembled. There is no clear explanation yet of the mix of wappens.

Before we examine the helmets in detail. We will look at the back of the cards.

our translation comes courtesy of a member of AHF.

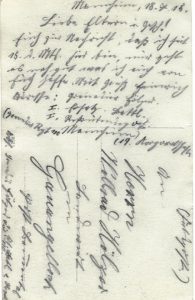

This first picture holds few surprises. A postcard to his brother in law from Heinrich Hölzer dated clearly1 March 1915 addressed:

To

Mr. F. Lengsfeld

policeman

in Mannheim

Lower (Untere) Clignet street

No.4, 3rd floor

Karlsruhe, February 28th, 1915

Dear Brother in law and Sister!

Dearest Greetings from

Karlsruhe sends

Heinrich. How are

you both? Hopefully

as well as I am.

This is consistent. Heinrich Hölzer from the BKA sends a postcard showing his unit that puts together ersatz helmets. The second picture says roughly.

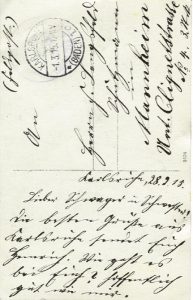

Mannheim, the 18th of July 1915

Dear Parents and siblings

Jus to let you know that I have been since the 15th of that month here,

I am still well, and the same for you I hope.

With greetings, Heinrich

Adresse: Grenadier Hölzer

I. Ersatz.Battl.

I. Rekrutendepot

(Grenadier Rgt. 110 Mannheim)

(19. Korporalschaft)

The gentelman who helped translate this card added this note: “That man’s handwriting is very “special”. I fear he is that farmers son and not very used to writing.” The card is addressed to:

To Mr.

Volkrad Hölzer

Farmer

in

Gauangelbach

Post Bammertal [“m” with bar means “mm”; south east of Heidelberg]

From:

Abs. Grenadier Hölzer 1. ErsBattl. 1. Rekr.

Rgt 110.

It seems reasonable that this unit’s mission ended with the arrival of the M15 helmet. In this case, it seems as though grenadier Holzer was sent to Grenadier Regiment, 110.

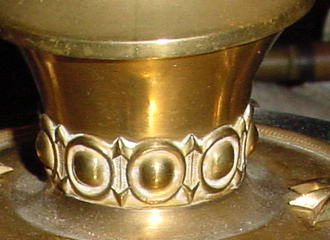

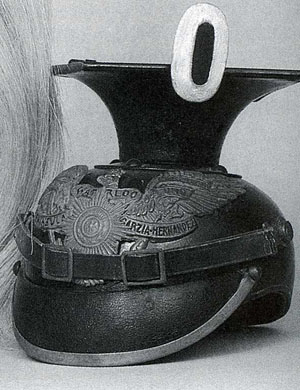

An example of a Kit Metal Helmet

The helmets themselves are a thing of simplicity. This example shows a complete helmet with the spike removed. There were 13 pieces to this helmet. These 13 pieces could be assembled by hand in the order of one through 13. The Helmmacher Abteilung provided the hands.

|

|

- The helmet body or bell made out of thin steel and covered with black enamel paint. The outer covering a shiny, black and reminiscent of the enamelware used on some mess tins. There were factory made holes in the bell for the spike, the wappen, the spine and the M91 posts. This was pressed out of one piece of steel. There was a ridge around the base of the bell to allow for the placement of the liner and the front and rear visors. The hole on top for the spike, had a raised flange edge. The wappen hole was unique in that there was a rectangle and two circular holes. The rectangular hole was for the wappen to fit through, and the circular holes, which are close together, could possibly have been for a Saxon or Mecklenburg plate like the example on the right below.

|

|

|

|

2&3. Two M91 posts. These were standard design to accommodate a 1 mm thick side hook. These were placed in the holes and the rear prongs bent to keep the posts in position.

|

|

- The liner made of very thin leather or a paper leather combination. These liners were deeper than the normal liner and had a split in the back. This split was fixed through the use of a snap. This example has the female end of the snap, but the male end is gone. The liner was laid on to the bell and crimped into the side ridges.

|

|

- The front visor made out of thin steel factory issued with a brass visor trim and faux brads on the corners. The faux brads are quite small with the exception of Saxon ones which approximate mormal size. In this example, the maker’s mark is engraved on the inside of front visor. The visor was placed into the ridges on the bell, and then bent down into position, holding the liner in place and the visors securely to the bell. The company was Firma von der Heyden in Berlin who also produced the first 50 metallhelmes for Bavaria.

|

|

|

|

- The rear visor made out of thin steel factory issued with a rolled steel blackened trim. Just like the front visor the rear visor was inserted in the ridges of the bell. And then bent down, holding the liner in place and fixing the rear visor firmly in place.

|

|

- The wappen. Made of brass, with a single tube loop to attach the wappen to the bell. This would allow for easy application through a matched hole in the bell. There is a slightly different system on this one example of a Saxon kit helmet. There are two holes drilled into the chest of this example wappen. It was believed that this might be a post war addition. The holes are too far apart for a landwehr cross. The only state wappen it could support is for Oldenburg. The holes are not even straight. But then this picture showed up:

|

|

- The spike is made of brass and originally of two pieces joined into one in the factory, the spike and the base. The spike could be turned by hand. The base had faux dome studs. The spike was crimped to the flange on top of the bell.

|

|

- A rear spine made of brass with two washers and square nuts for attachment to the bell through the two existing predrilled holes.

|

|

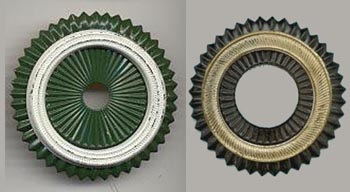

10&11 Two cockades in this example, a Prussian one on the left and a Reich’s cockade on the right. 48 mm with large holes and a slot to accept M91 posts.

|

|

- A leather two buckle chin strap. This strap has obviously been stretched out to go over someone’s chin, just by pulling.

|

|

- A head pad to cushion the head from the bell and the nuts. I do not know what material this is made of. However, it is quite fragile and gives the impression of a cardboard paper. Similar head pad’s are found in the helmets of some cuirassiers to pad the wearer from the metal helmet.

|

|

This example has provided a rare match between the soldiers of a very specific Abteilung and a specific type of metal helmet that we know was used in Prussia, Wurttemberg, Bavaria, Saxony and Baden. I’m sure there are errors in this but it is a fun explanation!

Women Regimental Chefs

Joseph P. Robinson.

These are the women who were Chef’s of regiments. I think this is a pretty complete list from 1913. It was customary for select regiments to appoint an Honorary Chef. Some regiments had hereditary chefs and others could be a foreign or German royal personage. Within the Bavarian army, the chef of the regiment was called the “Inhaber.”

|

Kürassier Regiment Königen (Pommersches) Nr. 2 Füsilier Regiment Königin (Schlesw.-Holst.) Nr. 86 She was the wife of Kaiser WilhelmII and the daughter of Herzog Friedrich von Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderberg- |

|

|

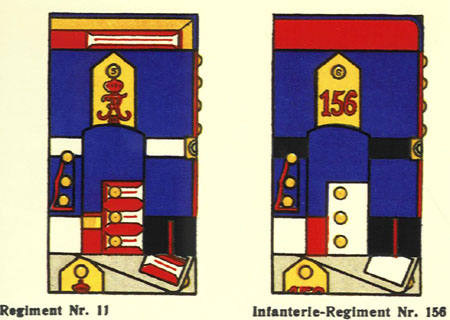

Grenadier Regiment König Fredrich III (2. Schlesisches) Nr.11 She was the sister of Kaiser II and the daughter of Fredrich III. She was the wife of Bernard of Saxe-Meiningen |

|

|

5. Westf. Infantrie Regiment Nr.53 She was the sister of Kaiser II and the daughter of Fredrich III. She was the wife of Prinz Adolph of Schaumburg-Lippe. |

|

|

Königin Elisabeth Garde Grenadier Regiment Nr.3 She was the sister of Kaiser II and the daughter of Fredrich III. Queen of Greece |

|

|

Füsilier Regiment von Gersdorff (Kurhessisches) Nr. 80. Margarethe Landgräfin von Hessen. She was the sister of Kaiser II and the daughter of Fredrich III. She was the wife of Landgraph Fredrich Karl of Hessen. |

|

|

2nd Lieb Husaren Regement She was the daughter of Kaiser II. She was the wife of Duke Ernst August of Braunschweig. |

|

| Dragoner Regiment König Fredrich III (2. Schlesisches) Nr. 8

Kaiser Wilhelm II daughter-in-law. Wife of Crown Prince Wilhelm. |

|

|

Ulan Regiment König Wilhelm I (2. Württemberg) Nr. 20 Queen of Württemberg |

|

|

Königin Augusta Garde Grenadier Regiment Nr. 4 Wife of Grand Duke Wilhelm I from Baden. |

|

|

2. Badischen Dragoner Regiment Nr.21 Wife of Grand Duke Wilhelm II from Baden. |

|

|

2. Großherzl. Mecklenbg. Dragoner Regiment Nr.18 Leib Grenadier Regiment König Friedrich Wilhelm III (1. Brandenbg.) Nr.8 Wife of Grand Duke Friedrich Franz IV of Mecklenburg-Schwerin |

|

|

Infantrterie Leibregiment Großherzogin (3. Großhzl. Hessisches)Nr.117 First wife of Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig from Hessen. Despite a divorce and remarriage of the Grand Duke Victoria Melita apparently remained Chef of the regiment |

|

|

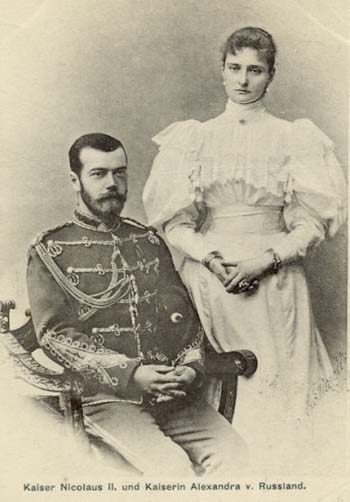

2. Garde Dragoner Regiment Kaiserin Alexandra von Rußland Queen of Russia |

|

|

Husaren Regiment Fürst Blücher von Wahlstatt (Pomm.) Nr. 5 Queen of Great Britain |

|

|

Füsilier Regiment Königin Viktoria von Schweden (Pomm.) Nr.34 Queen of Sweden |

|

|

Infantry Regiment Prinz Friedrich der Niederlande (2. Westf.) Nr.15 Emma Queen Mother of The Netherlands |

|

|

Husaren Regiment Königin Wilhelmina der Niederlande (Hann.) Nr.15 Wilhelmina Queen of The Netherlands |

|

|

Kurhessischen Jäger Battalion Nr.11 Queen Mother of Italy |

|

|

Louise Marguerite of Prussia–Infantrie Regiment Gen. Feldmarschall Prinz Friedrich Karl von Preußen (8. Brandenbg.) Nr.64

|

|

Women in Uniform

Joseph P. Robinson.

I’m not so sure why this became an area of collecting but it is growing. The Germans got into a large amount of propaganda obviously, but one of the “series” was Fräulein Feldgrau. These were young pretty girls in feldgrau uniform that I suppose had a sort of pin-up purpose. No nudity involved, just pretty faces. This is a family site and no, the turn of the century Germans would not go off the deep end. There were other “series” to include Fräulein Leutnant, and pictures of noble women in the uniforms of their regiments. We will try tp bring you these pictures and add as things come available.

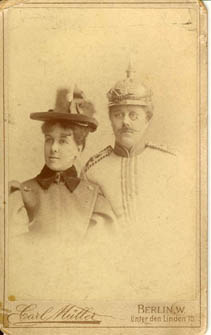

| From the collection of Brian Kostel, these old CDV’s show women with fake mustaches and beards. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Royalty also had uniforms. | The first biggee that got a lot of play was Viktoria Luise, the Kaiser’s only daughter. She lived to a ripe old age and was very popular as Vicki. She had a hand in writing many books including The Kaiser’s Daughter. Her signature was freely distributed in her older years. Shown below in the iniform of her 2nd Lieb Hussar Regiment. |

|

|

|

|

|

The Crown Princess — Cecile was described in the McDonough book as ” The only man in the Hollerzoleran household.” A lot of her pictures were with Vicki showing off her role as Chief of the 8th Dragoons.

|

|

|

|

| This is Alexandra the Great Duchess of Mecklenburg – Schwerin in the uniform of her 8th Grenadiers. Collectors would go nuts to see the rosettes on this unique helmet but the busch covers all. |

|

|

|

The wife of August Wilhelm (one of the Kaiser’s sons) as Chief of the 14th Dragoons. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Student Societies

Joseph Robinson

19 September 2006

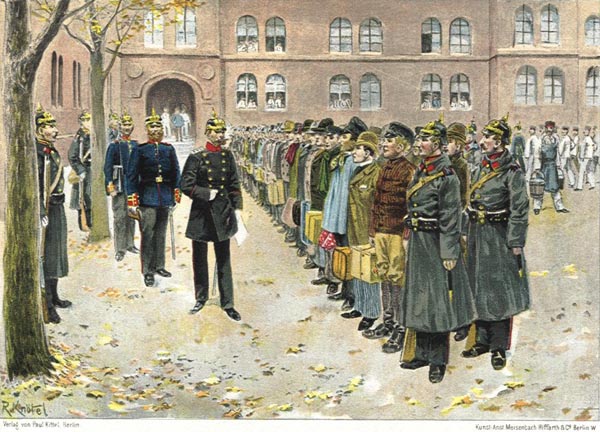

|

|

|

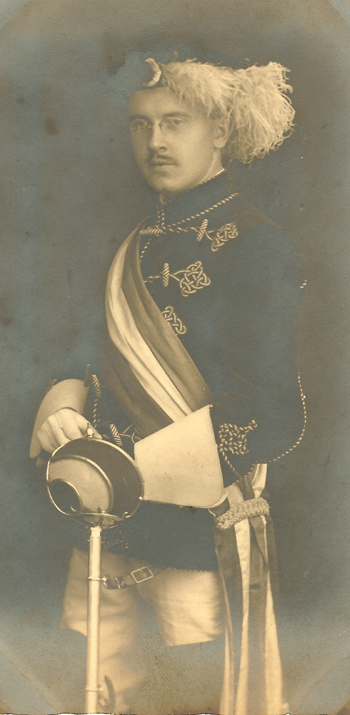

We have all seen these pictures. Students with swords generally dismissed as some sort of university fraternity. The intent of this article is not academic, but merely to bring collectors some knowledge about what this was all about. I certainly did not know and have had a lot of fun looking it up. There is not a lot of data in the pickelhaube references on this subject.(There was one short article on page 16-19 of the June 1998 issue of the Uhlan.) Nonetheless the pictures abound, and seem to come up often when looking at photographs. With the exception of military officers, almost every prominent man in German public life has belonged to a student fraternity, from the great chancellor downwards. However, these fraternities were male bastions where one could prove himself and show that he was not afraid of bodily harm and would not flinch when his honor was tested. |

| Each of us has a doctrinal view of what dueling is all about. A pistol duel can be easily visualized with two antagonists, each one trying to harm the other or even kill the other. Sword duels can be visualized two antagonists dancing back and forth in a ballet of thrusts. What the student dueling societies did was something entirely different. In dead earnest the students entered into something known as the Mensur. Dueling was a social institution in Germany. The honor code of nobility must be maintained. Wilhelm II declared that he would punish any officer who fought a duel, but would dismiss from the army any one who refused to do so. Satisfaction in dueling was showing the world that you had no fear just great honor. | |

| Student societies can trace their roots back to the Middle Ages. For our purposes, we will talk about three kinds of student fraternities extending from the mid-1800s to the start of World War I. Remember that almost nobody went to the university. Of those that did about 25% were in fraternities. The others were “savages”. The expense was immense and the requirements rather stiff. Applicants needed to have an Abitur certificate before attending. Therefore, the students we are talking about are the upper crust of professionals both aristocratic and upper bourgeois. The students were destined to fill the ranks of professionals throughout Imperial Germany. While these individuals did not directly enter into the military, there was still a great social value into proving one’s worth and bravery. In order to do this students would go to university, and frequently join a group of fellows. Known as a Burschenschaft, this group of fellows or a fraternity, took on three general forms. The first kind was a Landsmannschaft. They tended to be regional fraternities based on geographic location and tended to be more liberal. The second kind was a more normal Burschenschaft. These were national in nature and tended to be more right wing politically. The third kind was called a Korps. These tended to be more aristocratic in nature, and a discussion of politics was strictly prohibited. Amongst these three levels. There were dueling fraternities and non-dueling fraternities. The Catholic Church had prohibited the Mensur and generally the Catholic fraternities did not duel. there were a lot of fraternities. At one point it was noted to be more than 4000 different fraternities. The Stein collectors have in general given up in trying to identify all of the different branches. There was a book written in the 1930s that actually listed 1400 different coats of arms. |

|

|

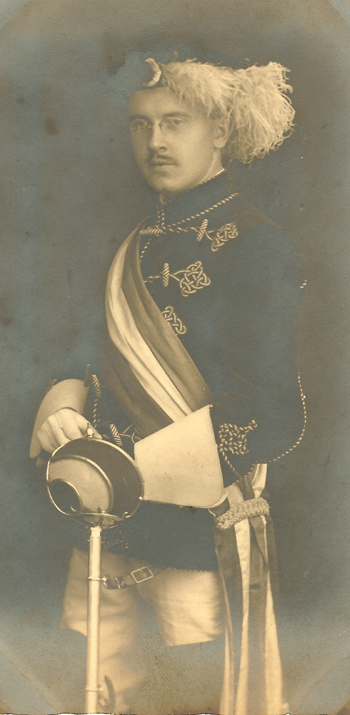

The use of Landsmannschaft, Burschenschaft, and Korps are often interchanged in literature. The different groups can be separated by their style of uniform, hat, and a brightly colored sash done in the colors of that fraternity. However all three of these had several things in common. There were generally three kinds of members. Membership was lifelong and alumni played an active role in the chapter. The first kind of member was irregular member. Irregular members were those who were physically unable to participate in a Mensur or whose parents refused to allow them to participate in a Mensur. The second type of member was a novice, also known as a pledge in the English language fraternities. The novices were also known as Foxes. They had not yet earned the right to participate in a Mensur. Typically, a new fox/pledge is not allowed to participate in the Mensur until after having completed one and a half to two terms of study, involving about one hour of fencing study daily instructed by the Burschenschaft ‘fencing master’. Some Burschenschaft had a shorter period of being a novice. The third kind of member, or Burschen, are full-fledged Korps students, eligible to become officers. Once again, there are three officers, called respectively the first, second and third, ‘in charge.’ The first is the chief, who presides at formal meetings and in the drinking-hall, where the Korps assembles officially on two evenings of the week. The second in charge manages all affairs relative to fighting, and is personally responsible to the association for all formalities relating to the duels of its members. The third in charge is secretary and treasurer. In most Burschenschaft, the president considered himself morally bound to see that all the members attend their lectures regularly. |

| Each novice is considered to be personally under the charge of one of the fellows, whose duty it is to keep him out of trouble and to be a role model. In addition, there was a position known as “Fox-Major”. This individual was in charge of all of the novices and provide instruction about the fraternity on a weekly basis. This individual wore a distinctive headpiece regularly adorned with fox accoutrements and would forever be allowed to use the initials “FM” after his signature. |  |

|

Fraternity life consisted of many jovial gatherings. There were ritual meetings and methods for drinking beer. One common device was called a Salamander. The top officer would open meetings with a salamander, where beer mugs would be slid along the table and then pounded in unison three-times. This device was used for opening and closing meetings as well as numerous toasts. There were also such things as beer duels. A full glass two opponents chug the brew and the winner is he who empties the glass first. The President can order any member to drink a quantity of beer as a punishment. Any full member can direct a novice to do the same thing. (As a side note, most fraternity houses had something called a Kotzbecken or puking sink. This practical device came up to just under chest level and had support bars on the wall to hold you up.) Singing was another indispensable part of every regular meeting. All members had song books and the songs tended to be patriotic. |

| Fencing | |

| The student Mensur is completely foreign to the idea of American doctrinal dueling. The two antagonists are not enemies, and often become close friends after the duel. There is no endeavor to kill one another. And most different of all there is no movement. The only allowed movement is the sword arm itself. The participant is known as Der Herr Paukant. The duel is always between two different fraternities. This is seldom conducted to overcome some slight, but rather to fulfill the requirements the fraternities place on dueling. Let us take a look at a picture of the Paukant. |  |

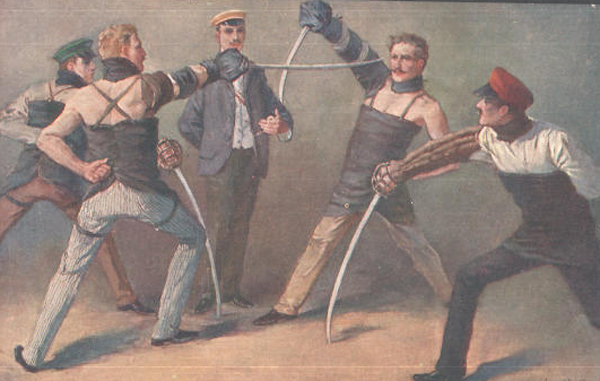

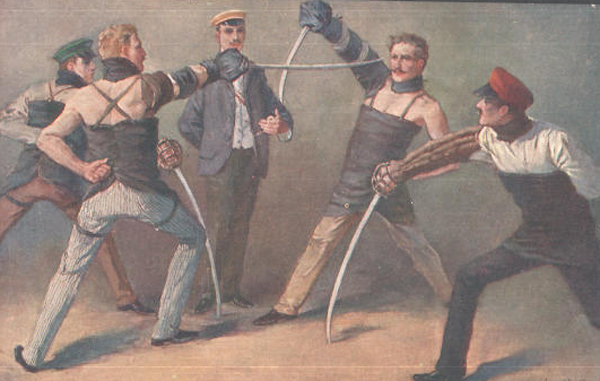

| The first thing to look at is the sword. This is known as the Schlager. The typical ‘Schlager’ (‘basket racquet’) used has a blade about 85 cm long and at least 1 cm wide (last 8″ sharpened). It has a conspicuous ‘basket grip’ that protects the hand and is typically decorated in the ‘couleurs’ of the student Burschenschaft the ‘Paukant’ belongs to. It is peculiar to a specific type of saber dueling. In swordplay there are basically two types of damage systems. “Impact” fencing (use of a blade to pierce mortally) and “blow” fencing (use of a blade to strike). The weapons used for the ‘evolved’ form of ‘blow fencing’ (“schlaeger fechten”) known as the ‘Mensur’ came to be commonly known in Germany as ‘racqueten’. The dueling sword differed from the Mensur racquet only in the nature of the blade, which on the former was curved and somewhat heavier. These two parallel forms of individual sword interaction grew largely side by side. The first consisting of actual dueling with sharp, pointed saber blades, the other consisting of the ‘Mensur’ (or ritualized fencing), with the ‘basket racquet’ (“Korbschlaeger”) or the ‘bell racquet’ (“Glockenschlaeger”). The picture below shows a normal duel. Notice that heavier sword and the movement. This is often confused with a student Mensur. | |

|

|

|

The Paukant also wore protective clothing that included reinforced leather aprons, arm coverings, neck protection, and steel ‘goggles’ to protect the eyes. The head and face are left totally unprotected.

|

|

|

|

|

| Continuing on to the duel itself each Paukant pair was separated by their seconds by one saber length or about 3 feet. The seconds then stood to the left of the Paukant. This distance was known as the Mensurabstand. A Paukant was not allowed to shorten or lengthen this distance. A Paukant was not allowed to back off or shift position. The left hand was placed behind the back, and the right hand held up in one of two general positions. The offensive position (left hand Paukant above.) was known as the Hochquart or high quart. This allowed one to strike down from a position of safety. The defensive position (Paukant on right above.) was known as the steile Auslage, or Steep Ward. Both of these positions protected the right side of the face. It was very possible to go through an entire Mensur completely protected. However, that required almost perfect execution. A major fault of the picture above is that the participants are too far apart. They should be separated by only one sword length and then also have the length of their arms. This brings up an interesting physics problem that the point of the sword is often several feet behind the opponents back. | |

|

Much importance is placed upon the perfect maintenance of stance of the participant, since moving to avoid blows with the body or foot is forbidden (“Mucken” or ducking.); moreover, such movement is considered cowardly and may be cause for premature cessation of the Mensur. 40 courses are considered the norm for completion of the Mensur, 15 courses for a Fox. A “course” (Gang) is a predefined amount of strikes. Always under ten and usually around four. The seconds kept track of them. If either of the ‘Paukant’ receive ‘Schmisse’ that are particularly serious, the contest may be considered satisfactorily completed at the discretion of the attending physician (known as ‘Bader’). In that event the ‘Schmiss’ will be sutured on site, although without local anesthetic!

|

| For a student and all of German Society, the badge of courage was the Schmiss (The dueling scar, or sometimes called the Renommierschmiss, or bragging scar), mostly on the left side of the face, where blows would fall from a right-handed duelist. This was borne by a generation of doctors, jurists, professors and officials, certifying the owner’s claim to manly stature. The dueling scar was certain to attract attention because it signified courage and breeding. There are stories that students would resort to self-infliction with a razor. Those who received their Schmiss in this less honorable way would frequently enhance it by pulling the wound apart and irritate it by pouring in wine or sewing horse hair into the gash.

|

|

|

A picture of a famous Nazi showing a horrible scar on his left cheek. It was a Schmiss. |

| Another example of a Schmiss, this one from the collection of Mike Huxley. Stories relate that females were attracted to people with such a scar. Somehow I doubt that. I just cannot imagine my wife waking up next to this face and thinking it is a bonus. |  |

| Comments by Readers | |

| A few corrections have come from various sources. This first one is from a former Fox Major. | “You should add to different groups of student societies the TURNERSDCHAFT. The Turnerschafts were establishes about 1819 and form a fraternity of patriotism, not nationalism and not chauvinism. The Nazis dissolved all student societies in order to establish their ideology. Duels and fencing was not allowed any longer. After 1950 most student societies founded their tradition again. By the way I fought seven duels and still have some scars on my head (with hair over) My corporation’s name is Turnerschaft Salia Jenensis, as you will remember.” |

| From an American observer. | I recall visiting XXXXX at Gottingen University and there was a formal vote taken by both corporations involved in the duel to allow me to be present as an observer. Because I had just returned from infantry and cavalry combat in Vietnam they invited me to watch. My memory was of how sharp the swords were and that the blades had to be straightened after each series of blows. During the duel of rapid blows it seemed I saw a piece of hair fall to the floor followed by a flow of blood from the head wound. Time out was then called and a doctor examined the wound. It was necessary for all the corporation members to vote to end a duel should their entrant be badly wounded. |

| A German citizen here in modern times. This was posted in AHF | I’m a member in a “Corps” named “Corps Cheruscia” Berlin in the WSC “Weinheimer Senioren Convent” , one of the German wide umbrella organisations for duty Mensur. I have fought 6 “Mensuren” from 1991 to 1994, without a “Schmiss” in my face, but the fights were hard on the other side – yeah, I was the winner in 3 fights, I lost 1 fight and 2 fights ended in a draw. I can describe every aspect of the student “Mensur”.a little mistake: your picture “Fencing” is not a fencing. Its a “Landesvater- Stechen” – take your student cap and hold it, that your best friend in the Corps can transfixing your cap with his “Schläger”, our swords. You can do the same thing with his cap. Than clasp his hand to pledge troth. This is a old ritual to pledge troth to the leader of the German countries in the middle age, because the students at the universities were associated in country groups till the end of 1815/ 1830. After the “Landesvater” you can request your girlfriend to embroider the slit in the cap with silver or gold yarn. A Landesvater is a special event all 5 years. Please note that every town has a special fight rule. You have to learn the typical town rule to fight in this town. |

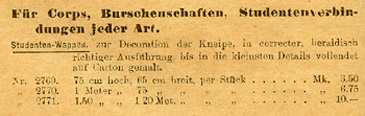

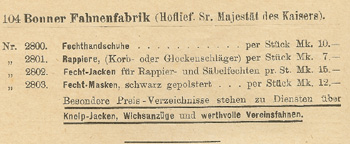

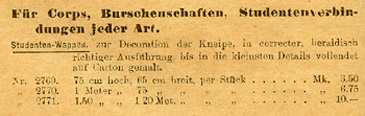

| We have two catalogs with many items for sale for students. I was surprised that there were not as many pictures as I would have liked. it seems as though the restrictions on dueling restricted the amount of kitsch available for sale. |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Military Service

Joseph Robinson

19 September 2006

We have all seen these pictures. Students with swords generally dismissed as some sort of university fraternity. The intent of this article is not academic, but merely to bring collectors some knowledge about what this was all about. I certainly did not know and have had a lot of fun looking it up. There is not a lot of data in the pickelhaube references on this subject.(There was one short article on page 16-19 of the June 1998 issue of the Uhlan.) Nonetheless the pictures abound, and seem to come up often when looking at photographs. With the exception of military officers, almost every prominent man in German public life has belonged to a student fraternity, from the great chancellor downwards. However, these fraternities were male bastions where one could prove himself and show that he was not afraid of bodily harm and would not flinch when his honor was tested.

Each of us has a doctrinal view of what dueling is all about. A pistol duel can be easily visualized with two antagonists, each one trying to harm the other or even kill the other. Sword duels can be visualized two antagonists dancing back and forth in a ballet of thrusts. What the student dueling societies did was something entirely different. In dead earnest the students entered into something known as the Mensur. Dueling was a social institution in Germany. The honor code of nobility must be maintained. Wilhelm II declared that he would punish any officer who fought a duel, but would dismiss from the army any one who refused to do so. Satisfaction in dueling was showing the world that you had no fear just great honor.

Student societies can trace their roots back to the Middle Ages. For our purposes, we will talk about three kinds of student fraternities extending from the mid-1800s to the start of World War I. Remember that almost nobody went to the university. Of those that did about 25% were in fraternities. The others were “savages”. The expense was immense and the requirements rather stiff. Applicants needed to have an Abitur certificate before attending. Therefore, the students we are talking about are the upper crust of professionals both aristocratic and upper bourgeois. The students were destined to fill the ranks of professionals throughout Imperial Germany. While these individuals did not directly enter into the military, there was still a great social value into proving one’s worth and bravery. In order to do this students would go to university, and frequently join a group of fellows. Known as a Burschenschaft, this group of fellows or a fraternity, took on three general forms. The first kind was a Landsmannschaft. They tended to be regional fraternities based on geographic location and tended to be more liberal. The second kind was a more normal Burschenschaft. These were national in nature and tended to be more right wing politically. The third kind was called a Korps. These tended to be more aristocratic in nature, and a discussion of politics was strictly prohibited. Amongst these three levels. There were dueling fraternities and non-dueling fraternities. The Catholic Church had prohibited the Mensur and generally the Catholic fraternities did not duel. there were a lot of fraternities. At one point it was noted to be more than 4000 different fraternities. The Stein collectors have in general given up in trying to identify all of the different branches. There was a book written in the 1930s that actually listed 1400

The use of Landsmannschaft, Burschenschaft, and Korps are often interchanged in literature. The different groups can be separated by their style of uniform, hat, and a brightly colored sash done in the colors of that fraternity. However all three of these had several things in common. There were generally three kinds of members. Membership was lifelong and alumni played an active role in the chapter. The first kind of member was irregular member. Irregular members were those who were physically unable to participate in a Mensur or whose parents refused to allow them to participate in a Mensur. The second type of member was a novice, also known as a pledge in the English language fraternities. The novices were also known as Foxes. They had not yet earned the right to participate in a Mensur. Typically, a new fox/pledge is not allowed to participate in the Mensur until after having completed one and a half to two terms of study, involving about one hour of fencing study daily instructed by the Burschenschaft ‘fencing master’. Some Burschenschaft had a shorter period of being a novice. The third kind of member, or Burschen, are full-fledged Korps students, eligible to become officers. Once again, there are three officers, called respectively the first, second and third, ‘in charge.’ The first is the chief, who presides at formal meetings and in the drinking-hall, where the Korps assembles officially on two evenings of the week. The second in charge manages all affairs relative to fighting, and is personally responsible to the association for all formalities relating to the duels of its members. The third in charge is secretary and treasurer. In most Burschenschaft, the president considered himself morally bound to see that all the members attend their lectures regularly.

Each novice is considered to be personally under the charge of one of the fellows, whose duty it is to keep him out of trouble and to be a role model. In addition, there was a position known as “Fox-Major”. This individual was in charge of all of the novices and provide instruction about the fraternity on a weekly basis. This individual wore a distinctive headpiece regularly adorned with fox accoutrements and would forever be allowed to use the initials “FM” after his signature.

Fraternity life consisted of many jovial gatherings. There were ritual meetings and methods for drinking beer. One common device was called a Salamander. The top officer would open meetings with a salamander, where beer mugs would be slid along the table and then pounded in unison three-times. This device was used for opening and closing meetings as well as numerous toasts. There were also such things as beer duels. A full glass two opponents chug the brew and the winner is he who empties the glass first. The President can order any member to drink a quantity of beer as a punishment. Any full member can direct a novice to do the same thing. (As a side note, most fraternity houses had something called a Kotzbecken or puking sink. This practical device came up to just under chest level and had support bars on the wall to hold you up.) Singing was another indispensable part of every regular meeting. All members had song books and the songs tended to be patriotic.

Fencing

The student Mensur is completely foreign to the idea of American doctrinal dueling. The two antagonists are not enemies, and often become close friends after the duel. There is no endeavor to kill one another. And most different of all there is no movement. The only allowed movement is the sword arm itself. The participant is known as Der Herr Paukant. The duel is always between two different fraternities. This is seldom conducted to overcome some slight, but rather to fulfill the requirements the fraternities place on dueling. Let us take a look at a picture of the Paukant.

| The first thing to look at is the sword. This is known as the Schlager. The typical ‘Schlager’ (‘basket racquet’) used has a blade about 85 cm long and at least 1 cm wide (last 8″ sharpened). It has a conspicuous ‘basket grip’ that protects the hand and is typically decorated in the ‘couleurs’ of the student Burschenschaft the ‘Paukant’ belongs to. It is peculiar to a specific type of saber dueling. In swordplay there are basically two types of damage systems. “Impact” fencing (use of a blade to pierce mortally) and “blow” fencing (use of a blade to strike). The weapons used for the ‘evolved’ form of ‘blow fencing’ (“schlaeger fechten”) known as the ‘Mensur’ came to be commonly known in Germany as ‘racqueten’. The dueling sword differed from the Mensur racquet only in the nature of the blade, which on the former was curved and somewhat heavier. These two parallel forms of individual sword interaction grew largely side by side. The first consisting of actual dueling with sharp, pointed saber blades, the other consisting of the ‘Mensur’ (or ritualized fencing), with the ‘basket racquet’ (“Korbschlaeger”) or the ‘bell racquet’ (“Glockenschlaeger”). The picture below shows a normal duel. Notice that heavier sword and the movement. This is often confused with a student Mensur. | |

|

The Paukant also wore protective clothing that included reinforced leather aprons, arm coverings, neck protection, and steel ‘goggles’ to protect the eyes. The head and face are left totally unprotected.

Continuing on to the duel itself each Paukant pair was separated by their seconds by one saber length or about 3 feet. The seconds then stood to the left of the Paukant. This distance was known as the Mensurabstand. A Paukant was not allowed to shorten or lengthen this distance. A Paukant was not allowed to back off or shift position. The left hand was placed behind the back, and the right hand held up in one of two general positions. The offensive position (left hand Paukant above.) was known as the Hochquart or high quart. This allowed one to strike down from a position of safety. The defensive position (Paukant on right above.) was known as the steile Auslage, or Steep Ward. Both of these positions protected the right side of the face. It was very possible to go through an entire Mensur completely protected. However, that required almost perfect execution. A major fault of the picture above is that the participants are too far apart. They should be separated by only one sword length and then also have the length of their arms. This brings up an interesting physics problem that the point of the sword is often several feet behind the opponents back.

Much importance is placed upon the perfect maintenance of stance of the participant, since moving to avoid blows with the body or foot is forbidden (“Mucken” or ducking.); moreover, such movement is considered cowardly and may be cause for premature cessation of the Mensur. 40 courses are considered the norm for completion of the Mensur, 15 courses for a Fox. A “course” (Gang) is a predefined amount of strikes. Always under ten and usually around four. The seconds kept track of them. If either of the ‘Paukant’ receive ‘Schmisse’ that are particularly serious, the contest may be considered satisfactorily completed at the discretion of the attending physician (known as ‘Bader’). In that event the ‘Schmiss’ will be sutured on site, although without local anesthetic!

For a student and all of German Society, the badge of courage was the Schmiss (The dueling scar, or sometimes called the Renommierschmiss, or bragging scar), mostly on the left side of the face, where blows would fall from a right-handed duelist. This was borne by a generation of doctors, jurists, professors and officials, certifying the owner’s claim to manly stature. The dueling scar was certain to attract attention because it signified courage and breeding. There are stories that students would resort to self-infliction with a razor. Those who received their Schmiss in this less honorable way would frequently enhance it by pulling the wound apart and irritate it by pouring in wine or sewing horse hair into the gash.

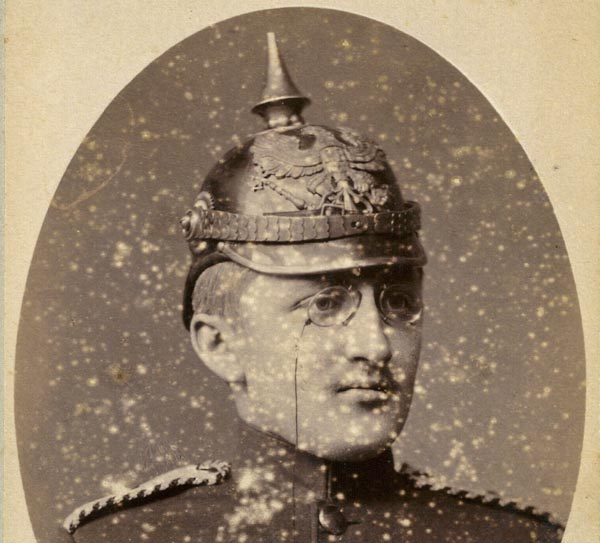

A picture of a famous Nazi showing a horrible scar on his left cheek. It was a Schmiss.

Another example of a Schmiss, this one from the collection of Mike Huxley. Stories relate that females were attracted to people with such a scar. Somehow I doubt that. I just cannot imagine my wife waking up next to this face and thinking it is a bonus.

Comments by Readers

A few corrections have come from various sources. This first one is from a former Fox Major.

“You should add to different groups of student societies the TURNERSDCHAFT. The Turnerschafts were establishes about 1819 and form a fraternity of patriotism, not nationalism and not chauvinism. The Nazis dissolved all student societies in order to establish their ideology. Duels and fencing was not allowed any longer. After 1950 most student societies founded their tradition again. By the way I fought seven duels and still have some scars on my head (with hair over) My corporation’s name is Turnerschaft Salia Jenensis, as you will remember.”

From an American observer.

I recall visiting XXXXX at Gottingen University and there was a formal vote taken by both corporations involved in the duel to allow me to be present as an observer. Because I had just returned from infantry and cavalry combat in Vietnam they invited me to watch. My memory was of how sharp the swords were and that the blades had to be straightened after each series of blows. During the duel of rapid blows it seemed I saw a piece of hair fall to the floor followed by a flow of blood from the head wound. Time out was then called and a doctor examined the wound. It was necessary for all the corporation members to vote to end a duel should their entrant be badly wounded.

A German citizen here in modern times. This was posted in AHF

I’m a member in a “Corps” named “Corps Cheruscia” Berlin in the WSC “Weinheimer Senioren Convent” , one of the German wide umbrella organisations for duty Mensur.

I have fought 6 “Mensuren” from 1991 to 1994, without a “Schmiss” in my face, but the fights were hard on the other side – yeah, I was the winner in 3 fights, I lost 1 fight and 2 fights ended in a draw. I can describe every aspect of the student “Mensur”.

a little mistake:

your picture “Fencing” is not a fencing.

Its a “Landesvater- Stechen” – take your student cap and hold it, that your best friend in the Corps can transfixing your cap with his “Schläger”, our swords. You can do the same thing with his cap. Than clasp his hand to pledge troth.

This is a old ritual to pledge troth to the leader of the German countries in the middle age, because the students at the universities were associated in country groups till the end of 1815/ 1830. After the “Landesvater” you can request your girlfriend to embroider the slit in the cap with silver or gold yarn.

A Landesvater is a special event all 5 years.

Please note that every town has a special fight rule. You have to learn the typical town rule to fight in this town.

Or the opponent have to learn my rule in Berlin to fight with me.

We are hard fighters in the Corps Cheruscia, hard rules, strict against “Mucken”, but there are other towns with soft rules.

And there is a big change in this generation – only a few young business man from a modern university are prepared to fight after the old rules today.

The German fencing is dying – I’m a member of the last hard generation – 10 years in the future there is only beer in the student societies. I see this – its a shame.

We have two catalogs with many items for sale for students. I was surprised that there were not as many pictures as I would have liked. it seems as though the restrictions on dueling restricted the amount of kitsch available for sale.

Looking Deeper Into History

Looking Deeper into History.

Joseph P. Robinson.

20 August 2005.

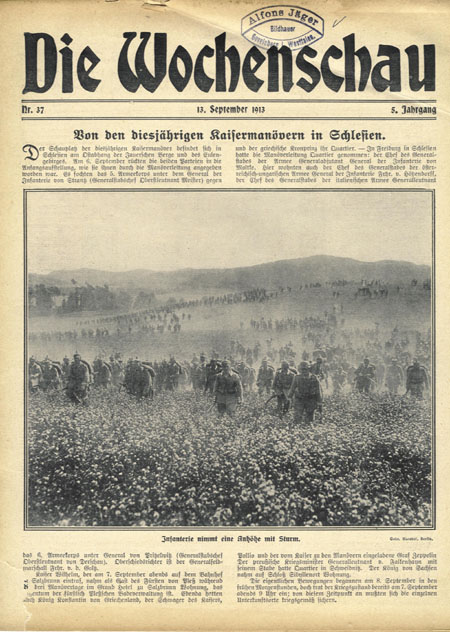

This is an incredibly famous picture. Students worldwide of World War I have gazed upon this picture to get a feel for the German assault in France and Belgium in 1914. History book after history book has copied this picture, cropped it changed it may be a little bit and included it in their works. For instance, the 2003 “All the Kaiser’s Men” on page 16 includes this photo with the caption: German infantry advance to contact in France August 1914. Not to single this work out as collectors and historians will recall the same picture from childhood. This is an oft repeated picture with maybe no more famous picture then this representing the German attack in 1914.

There have been questions as folks have blown the picture up and faintly discerned guard Litzen are on the uniforms and maneuver bands on the helmets. This did not make sense, especially given that some sources attributed the picture to Lorraine, where no guard units fought. The helmet detail of the maneuver bands was faint at best, maybe even airbrushed, but certainly would lead to some questions. The pictures below show the 11th Grenadier Litzen and maneuver bands worn by an artilery unit from a 1912 picture.

Below is a source picture. It comes from the 13 September 1913 copy of a German newspaper. The main title says from this year’s Kaiser Maneuver in Schlesien. Further reading attributes the maneuver to the VI Army Corps. VI Army Corps definitely came from the area cited. The Litzen on the uniform might indeed be from the 11th Grenadier Regiment of the VI Army Corps.

There is no way to prove exactly what this is a picture of. The photograph may have indeed, predated this newspaper significantly. One thing is for certain and it will certainly change the way we look at traditional histories. This picture was not taken after 13 September 1913, and it was not taken in France, Belgium or Lorraine. This just goes to show that collectors and historians cannot rely upon “conventional wisdom” when dealing with any issue.

There is no way to prove exactly what this is a picture of. The photograph may have indeed, predated this newspaper significantly. One thing is for certain and it will certainly change the way we look at traditional histories. This picture was not taken after 13 September 1913, and it was not taken in France, Belgium or Lorraine. This just goes to show that collectors and historians cannot rely upon “conventional wisdom” when dealing with any issue.

Life in a Garrison Town

Joseph P. Robinson 10 Aug. 2004

This book written in 1902-3, was banned in Germany , and the author found himself the object of courts martial. . The book was banned as it “libeled superior officers.” True, but was generally admitted to be common course by the Minister of War after the trial. The maladies pointed out generally follow what I have learned of Prussian Officers. The author, Lt Bilse, detailed what he saw as horrible problems in a society of the elite officers in a remote garrison in Alsace-Lorraine.

It is not that different from life in a US garrison town in Germany in the late 20th century. The 1904 English translation missed the key word small garrison. While much is made of the omission, you get the idea easily. The contents while allegedly fictional, were easy to spot as the garrison of Forbach. You get the impression this is some sort of cavalry organization but it is the home of 10. Lothringisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.174 after 1911, and train battalion earlier then that. The book was based on a Train Battalion. Why there was such an effort in the book to cover the regimental name in the part of the book that covers the trial of Bilse.? I do not know however, there is definitely an avoidance of who, what, where, and when.

The issues uncovered in “fiction” were:

- A regimental commander (Similar to a modern US Battalion commander.) who made what Bilse considered unreasonable decisions.

- A regimental commander who was blackmailed under the sway of a subordinate’s dominant wife.

- Unfaithful wives and officers.

- Officers in horrible debt.

- An officer who lied leading to the undeserved punishment of an OR.

- Abusive treatment of an OR.

- A senior NCO who lied leading to the trial and dismissal of another NCO.

- A Senior NCO “on the take”.

- An officer who deserted and ran away with another officer’s wife.

#1 – 3 are fairly standard complaints. Juniors frequently despise and judge seniors (right and wrong) and marital infidelity exists in all parts of society. (Janet would cut my ears off though). What is not standard is that Prussians were expected to duel to avenge their

honor. Dueling had been outlawed by the Kaiser (in an effort to keep up numbers in a chronically short officer’s corps). If you did duel you would be sentenced to fortress arrest for a couple months as it was illegal. If you chose not to duel you would be found a coward by a regimental court of honor and drummed out of the service for conduct unbecoming. Fortress arrest was always for choice. You had no choice but to duel if you wanted to stay in the army. The book relates a sad story of a captain whose wife ran away after a torrid affair with a lieutenant. The captain was obliged to challenge the lieutenant to a duel to defend the honor of his now missing wife. During the duel the captain was horribly wounded and had to be medically pensioned. So he lost wife, family, income, health and job. Once again the unhappy couple picture that dominate German marriages come to light.

#4 seems to be endemic of Prussian Officers. Marriage was done with income in mind. The father in law was expected to pay off the officer groom’s debts and the bride was expected to bring monthly income into the marriage. Bilse painted a picture of unhappy wives in many cases. In one case a lieutenant finds his wife to be incapable of providing the income he needs to live. Officer salaries provided almost no income to the family and in the small garrison leisure was spent at the officer’s casino where gambling took place. In debt officers often turned to Jews for lending. This social group was then badly besmirched and anti Semitism grew as moneylenders were blamed for all financial problems. One story is of a lieutenant who bought 10,000 marks of furniture on credit, borrowed against it, and then sold it! When the creditors collided a judge had to make peace.

#5 seems unsurprising.

#6 was strictly forbidden in the Prussian Army. The victim was extremely hesitant to say anything for fear of worse punishment. He tells the story of an abused batman who deserted rather than take more abuse. I have seen Ukrainian officers in the 90’s literally beat the heck out of an OR for making a mistake. Such behavior was forbidden.

#7. seems unsurprising.

#8 while unsurprising, is interesting in that he successfully targeted: One Year Volunteers (OYVs). Not only would he hit them as recruits but would accept payment annually during training, from some to lessen the severity of their duties. (This is the first time it dawned on me that OYVs did annual duty. Makes sense just never thought about it.)

#9. Rare but I’ve seen it. Even from a combat zone!!!!

So all in all I’d say much ado about little. A good fast read but not a lot of helmet details. What has become obvious is that officers moved. Transfers and moves in disgrace were common. So more support for double holes of officers. Staying in an out of the way regiment was not career enhancing. Getting in trouble or bringing negative attention to your unit was bad. Some things never change.

How You Became an Officer

Joeseph P. Robinson

26 May 2005

This article started out as a hunt for information on German imperial cadet helmets. As one thread lead to another, I found that I had to learn more to figure out what I wanted. It took a long time to have it all fall into place. The book For King and Kaiser by Steven Clemente finally provided the rest of the insights I needed in English. What I found surprised me. Given a lifetime opinion of officer’s, general staffs and pre-commissioning training formed in the US Army and by reading English language accounts of mostly English officer ways, I soon found the Germans were quite different. For each and every rule there were always exceptions.

We Value Loyalty and Obedience … exclusively.

It is outside of my scope to go back to the historical foundation of the officers in Prussia but it is important to know that it came from a feudal structure with the service of vassals to the king. Nineteenth century Prussians seemed to make out as though this was some sacred bond when medieval reality was different as kings had difficulty enforcing fealty. None the less this bond of vassal to king and obedience to his will dominated the entire scene. We wanted and insisted on loyal officers. Ones we could trust through thick and thin no matter what to be loyal to the king. Led by the nobility of the eastern provinces known as Junkers , The admission to the officer ranks had to be tightly controlled to enable only the loyal obedient types to enter into this most respected and sacred profession.

Oh crud the population and army is expanding.

The first kink in the armor was size. In 1914 the army was 761,000 men, 26,000 regular officers and 25,000 officers in the reserve.[i] More officers were needed than the nobility could provide. Historically there were nobles and officers from traditional officer families. These were good solid stock that could be counted on. Now expansion would find us accepting others into the fold so the Junkers had to find a way to restrict entry into the fold to only those who had the right attitude.

In general there were three classes of people.

- The nobility and with them traditional old officer families.

- The middle class. Some quite rich but families without the benefit of nobility.

- The lower class.

Class #1 had always filled officer ranks. Now, due to the size of the Army, some of class #2 had to be let in and under no condition what so ever would anyone from class #3 enter. Some is a relative word. By 1913, 70% of the army was middle class and 48% of the generals were middle class.

Well, if the 1st class guys had to have some #2s added in they certainly didn’t need to hang out with them. The tool to do this was the elite regiment. At first all of the #1s went to cavalry regiments. However, not all nobility could afford the extra expense of maintaining a horse etc. so the Foot Guard regiments became exclusive too. The bottom of the totem pole was the technical regiments of Pioneer and Foot Artillery. Those fields that required thinking were good for the #2s, the #1s would focus on saber waving. There was a lack of prestige as well as technical schools required. Technical schools meant having to pass courses as well as taking time.

Even by the time of the death of Fredrick the Great 10% of the army were #2s and they were all focused in Pioneer and Foot Artillery regiments. [iii] Regimental exclusiveness did not end. By 1913, 16 regiments were exclusively noble, Eighty % of cavalry officers, 48% of infantry and 41% of field artillery were noble. A few middle classers made it into the guards regiments. These were known as Concession Joes (Konzessionschulzes) and were not very welcome.[iv] An example from the 1912 Rangliste gives 36 of 36 non-nobles in IR154.

The following table gives you a feel for branches in 1861.[v]

TABLE 1

| Types of Regiments | Nobles % | Non-Nobles % |

| Infantry Guards | 95 | 5 |

| Infantry Line | 67 | 33 |

| Cavalry Guards | 100 | 0 |

| Cavalry Line | 95 | 5 |

| Artillery Guards | 67 | 33 |

| Artillery Line | 16 | 84 |

| Engineers | 16 | 84 |

* For some reason I was never able to find reference to Train Battalions. No telling where they fit but as they were not saber guys probably quite low.

Did I forget that we wanted quality?

Short answer is that is wasn’t that important. In fact it could be a threat. As more #2s entered the officer ranks with good solid skills those #1s who did not posses those skills or scores had to be protected. The American army is rife with nepotism but still the son has to have certain minimum skills. Not so in the Prussian ranks. You had to have birth, loyalty and obedience. Attitude could make up for many other failings. In all schools there were exceptions made to allow instructors to give extra credit to candidates with good attitudes. So a non-passing score could be rescued by deportment. Likewise a superb score of a #3 could be made failing by his “attitude”.

Schools were nothing like in the USA

The German school system provided the road into commissioning. Just like the US system but it is REALLY different. In today’s US world you go to primary, (8 years) secondary school, (4 years) and then, when 18 years old, college (4 years). If that college is an academy like West Point , you are commissioned at graduation. You can join the Reserve Officer’s Training Corps (ROTC) in a standard university and be commissioned upon graduation after at least a couple years of cadet training. All commissioned folks have 16 years of school a college education and a commission as a second lieutenant at about age 21 or 22. Source of commissioning matters not after young lieutenants get into their units. Nepotism (nobility) does.

Not so the Imperial German. The striking thing about the German officer is youth. Far younger than any of his western counterparts you could find officers at 17. Without talking maturity or education you find yourself looking at long service Germans rushing to get commissions and starting the clock on seniority. You could go the cadet route or the Fahnenjunker civilian route. Source of commission is very important as is nobility.

If we look at the American system everyone goes to school until age 18 and graduation from secondary school. Germans started at age 6 and had to go to age 14. This was primary school or Volksschule. Unlike western public schools Imperial German secondary school was not free to the parents. It is also VERY confusing because if the child was going to attend secondary school he transferred into a private secondary school at age 9. So parents had to start shouldering the economic costs of the education from age 9 until they could stop supporting the child. If the child would not be sent to secondary school he would remain in primary school until age 14 all at no additional cost to the parents.

So now you see why the emancipation of students became a major concern of families. Perhaps you begin to ferret out why commissioning and self sufficiency seemed so urgent. You also see that families had to decide very early (age 9) to bear this expense or not.

Two basic types of Secondary Schools

While there were several types and focuses there were basically 2 types of secondary schools; “6 year” and “9 year”. They were the same except for the addition of 3 more classes in the 9 year version. At the end of 6 years of secondary school you stood at the age of 14 the required schooling age.

The epitome of this education was to take an exam called the Abitur. After 9 years of school. Passing this exam guaranteed you good jobs. However you had to stay in secondary school until age 17-18 and pass a very difficult test. You could also leave school with a certificate of the highest grade qualified for. About 30% of the 9 year secondary graduates earned the Abitur.[vi]

A test taken 3 years earlier was often far more important to student and families. Known as the

One Year Certificate qualification, you could take it at the end of 6 years and if passed you qualified to be a One Year Volunteer (OYV). This meant only one year of service. The cost however was huge almost 2000 marks or the equivalent to a year in the university. Why would one do this? The advantage of being able to seek a reserve commission was worth going into debt to be a OYV. [vii]

You could also go to a cadet school. Cadets were an interesting lot. By 1910 2/3rds of the cadets were non-noble. [viii]The major investiture was the quasi-formal clothing ceremony. The picture of the Saxon Cadet I have should show how indifferent the issuers were for size of these issues of the lower cadet schools. Prussian lower schools did not wear helmets but each school had a unique uniform. If it was too large you had no recourse in this issue uniform but to grow into it. [ix] Cadet life seemed to revolve around efforts to find food as their normal fare was inadequate. Some Saxon cadets moved into the Prussian system but Bavaria stood alone and arguably always better. Saxony did maintain a separate cadet corps.

“The Doctorate is the calling card but the Reserve Commission is the open door.”[x]

German society was made of haves and have less’. To be a have you needed a commission. It didn’t make you noble but allowed you to do work in honor for a lifetime. A reserve commission allowed you to be one of the elite of society. True, not an active officer but a pretty good deal that lasted a lifetime.

You could take the OYV examination at the end of the 6th year of secondary school or after 6 years of the 9 year school. You didn’t have to finish the whole nine years. The OYV certificate acted as a diploma of sorts for many employers. An interesting point is that OYVs did not have to enter active service for their year until they were 20. So the candidate had years for education or employment.

An additional certificate, the Prima certificate was supposedly a requirement to take the Fähnrich exam. Reality in officer selection allowed for royal dispensation which ensured all the “right” folks could take the exam. Or even not take the exam and have an automatic pass. As a side, the Bavarian system was far more rigid requiring an Abitur to get a commission. As a result by 1914 only 15% of the Bavarian officer’s had noble titles. [xi]

The number of dispensations is always played down. Not that many is the conventional wisdom. Let’s take a look at test totals for a couple years:[xii]

TABLE 2

| Year | Civilians taking Fähnrich test | Cadets taking Fähnrich test | Total taking Fähnrich test | Officer test taken after was school | Selekta Cadets | Total Officers. |

| 1895 | 488 | 374 | 862 | 1179 | 82 | 1261 |

| 1900 | 344 | 351 | 695 | 970 | 88 | 1058 |

| 1907 | 315 | 337 | 652 | 925 | 63 | 988 |

Several hundred took the officer test without taking the Fähnrich test. That is quite a few dispensations and exceptions by my counting. In 1900 holders of the Abitur (and anyone with a year in University) were exempted from the Fähnrich exam[xiii]. If there were about 100 dispensations then about 200 Abitur holders skipped the exam. Of the 25,670 aspirants between 1870 and 1914 who decided to leave school early and take the Fähnrich test 43% of those were cadets[xiv].

Cadet School aspirants were far more desirable to a regiment than a civilian taking the Fähnrich test. In 1871 the senior cadet school has 700 cadets and supplied 40% of the army”s officer requirement. By 1889 the number of cadets had risen to 960 and the permanent home at Gross-Lichterfelde was established. This was the senior institution. Relate it to the civilian schools, the top 3 grades from ages 14-17. There were no less than eight junior campuses which fed the senior institution. (Köslin,Postdam,Wahlstatt, Bensberg, Plön, Oranienstein,Naumberg, and Karlsruhe .) You started at age 10 at the lower school and moved to the senior school at about age 14. Families paid for cadet school. It was not free or subsidized. The number of officers provided annually during the 20th century was 240.[xv]

The incentive again was to get these boys out to earn a wage and not burdening the families with school costs. Scholarships were available to help defray the cost and as a tool to ensure unwanted folks could not afford it.

So What Were the Steps to Becoming an Officer?

As you can imagine the steps were full of exceptions and changes all aimed at ensuring the right guy got in and the wrong guy did not. The basic ten steps to commission were similar for both the civilian method, Fähnenjuker, or the cadet schools. Some of these had more exceptions than others.

Step 1. Find a Regiment

All Guard and Cavalry regiments actively recruited nobles to keep the regiments pure. Sort of like modern recruiting, all methods were used to lure the young nobleman. They used fancy uniforms and depot locations near fashionable large towns. Guard and cavalry units could expect additional income of 1000 marks per month for a candidate Remote lower regarded regiments often had problems attracting new blood. None-the-less, they insisted on a rigid class and social pick in step 2.[xvi]

The maintenance of high social standards led to great shortages. 8% short in 1889 of total officer billets. In 1902 56 infantry regiments received no applications! This was blamed on middle class folks not wanting to wade through the army’s prejudice. [xvii]

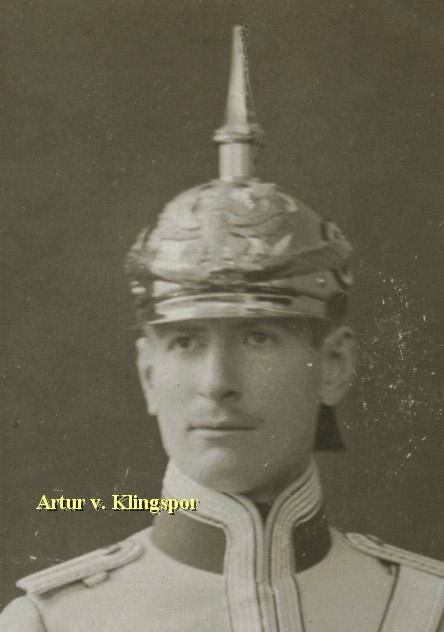

Step 2. Get Regimental Colonel to sponsor you to qualify.

This was the key and maybe most difficult step on the ladder. The family was looked at in detail as well as the candidate. Sufficient income was required and the regimental commander and his other officers didn’t want to accept a fiscal problem maker. A somewhat sad story is told by Vera von Etzel about how Artur v. Klingspor made it into the Kürassier-Regiment von Seydlitz (Magdeburgisches) Nr.7. Very expensive gear at that time and a burden even for his father, Lieutenant Gen. Leo v. Klingspor. The older brother was subsidized by his father and received his commission. But he was subsidized after his younger brother, Hans Arvid, died while in the academy. Perhaps the loss of a son required his father to make sure his surviving son was in the ‘best’. But the enormous cost of a ‘fancy’ regiment would keep the regiments populated by the more affluent – the ‘vons’.[xviii] The father and son went to a dinner to be seen by all a one night precursor of step 8. The Colonel would not give final approval until the Fähnrich exam was passed or in the bag. Cramming with a tutor for the exam was a standard practice.

Step 3. Pass the Fähnrich examination

Remember you were supposed to have a Prima certificate or dispensation to gain entry. 90% had a Prima Certificate. 75% passed the first time. You could take it again and few if any failed the second time. If indeed they did fail the second time it was into the ranks as an OR. In 1890 the Kaiser demanded leniency in grading. If leniency failed he used dispensations which totaled over 1000 between 1901 and 1912.[xix]

At the end of 6 cadet years or the age of 17 the cadets took the Fähnrich exam and merged into the commissioning process. Cadets were a little different because they were called Brevet Fähnrich. If you really did well on the Fähnrich exam you could be selected as a Selekta cadet and maintained at the school. They became cadet non commissioned officers and “ran” the non-senior cadets in the following year. There was a huge advantage of being a Selekta. If you passed the Officers exam you got commissioned. No need to be voted on buy the officers of the regiment.[xx] You could also stay at the academy, delay commissioning and try for the Abitur. The Selekta helped you for the rest of your military life. The Abitur was a civilian life advantage.[xxi] Never the less the number of military Abitur holders grew steadily from 1/3 in 1880 to 2/3rds in 1912. The number of middle class officers who saw the lifelong civilian advantages of the Abitur took sway.[xxii]

Step 4. Spend time in the ranks in the regiment

The folks that passed moved into the regiment as an OR but was referred to as an “avantageur”. Officially, the title was “Officeraspirant” that title was officially changed in 1899 to “Fähnenjunker”. He wore a portapee that identified him. He lived in the barracks for a period that varied by regiment from 6 weeks to 1 week. He started as a Gemeiner and when he moved out became a Gefreiter. All costs associated with his service were borne by him like a OYV. At this point he could also have a civilian batman.[xxiii]

When promoted to unteroffizer he got to eat at the officer’s mess. At this point he started being called Fähnrich. The word Portapeefähnrich went away in 1899. A Fähnrichsvater was appointed to be his mentor. Long drinking bouts and rules of the mess were common place. While the Fähnrich was encouraged to spend freely, indebtedness was a major embarrassment for the entire mess. Step 4 passed quicker and quicker. At first 6 months, the time shortened to three months (two if you came from a cadet school) by the turn of the century.[xxiv]

There were exceptions as some cadets left the academy with some advanced training and were considered Patent Fähnrich. They never were privates just Gefrieter.

The time in the ranks was so short folks didn’t learn the system. Only the reserve officers who went through the year as a OYV understood the difficulties of the OR.

Step 5. Be promoted to Fähnrich “if all went well”.

The aspirant applied to the colonel that he was “qualified” and deserved a military qualification certificate (Dienstzeugnis). If approved by the colonel and ALL of the officers of the regiment he was officially promted to Fähnrich and paid a salary. He also got to wear the silver sword knot. Between 1892 and 1894 for example, of the cadets 59% became Brevet Fähnrich, 10% Patent Fähnrich and about 1/3 were Selekta. [xxv]

Step 6. A course at the Kriegschule.

Cadet Abitur holders, Selekta cadets and civilian Abitur holders who had been University students for a year were exempted from this requirement. However, If you look at the ages you see that expanded civilian education took time and money whereas you could skip the education and go into the commissioning system and start making money and seniority. This course shrunk in length as the need for officers became more pressing and the desire became to commission in 1 year. At the end of the course you took the officer’s exam. This course eventually went to seven months in length.[xxvi]

Step 7. Pass officer exam (become a DegenFähnrich) and return to regiment.

Selekta Cadets went straight to step 10 if they passed. . Passing was not a problem (98% pass with re-take option.). Obedience and attitude came before grades. It was considered far easier than the Fähnrich exam.[xxvii] At the regiment the Fähnrich waited (briefly) for a vacancy and for the next steps to be completed.

Step 8. Regimental officers balloted, to see if they agree to accept candidate.

Selekta cadets did not have to undergo this. Majority vetoes were final. Minority vetoes had to be sent to the King for decision. If you failed you were either sent to another regiment for another try or to the reserves in disgrace or with a major stigma. Few candidates failed as it required going against the Colonel’s wishes. Some were rejected in full knowledge because of a lack of personal wealth in which case the candidate was sent to another regiment without stigma. [xxviii]

Step 9. Colonel Recommends Promotion to Second Lieutenant to Kaiser

The Fähnrich became a second lieutenant and a member of the social elite. EXCEPT if you were in the Foot Artillery or Engineers. These two branches considered the newly commissioned as supernumeraries until they had served one or two years, attended technical school, and passed a qualifying exam. [xxix] Technical schools were viewed by the nobility as “schools for plumbers”. [xxx] Is there any question why the nobles eschewed these branches?

Step 10.Promotion is Officially Gazetted[xxxi]

There were all sorts of rules for seniority and backdating dates of rank but it is outside my scope to dwell on these. Abitur holders finally got payback and got their dates of rank predated 2 years.

Congratulations you are an Officer or “Trick or Treat you are in the Fleet”.

Being one of the elite you found yourself in another world. There were no rules for promotion. That’s right no rules. Seniority and noble connections both mattered. A normal progression was 8 years, to First Lieutenant, 14 to Captain, 25 for Major, and 30 for Lieutenant Colonel. Pay was not reasonable as it was 1/5th of his American counterpart.[xxxii]

Low pay with high status meant that marriage had to be a business deal where the girl brought the “bacon” to the table. It was not unusual to use a marriage agency nor for the brides father to assume the officer’s existing debts. Marriage had to be approved by the regimental commander to ensure the woman had enough money and an unblemished record. [xxxiii] Have you ever noticed how unhappy German brides look in their wedding pictures? Maybe it was cultural. At least my wife smiled when we got married.

So life wasn’t always rosy but now we know how you got to this social plateau. Clemente’s book was heavily relied on for citations in this article but as you can see the pages and information had to be rearranged. What are my conclusions?

- Prussian Officers were far younger and less well educated than their western counterparts.

- Wealth and social position drove the train.

- There were many regiments where the have – less types resided.

- For every rule there were exceptions made for the right person.

So there it is in short (well sort of not exactly 300 pages.). Have at it all critiques very welcome.

——————————————————————————–

[i] Clemente, Stephen, For King and Kaiser, Greenwood Press, Westport , CT , 1992, p205.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Clemente, Stephen, For King and Kaiser, Greenwood Press, Westport , CT , 1992, p3.

[iv] Ibid. pg 206.

[v] Ibid. pg 16

[vi] Ibid. pg 32

[vii] Ibid. pg 33

[viii] Op cit. Clemente, pg 111.

[ix] Ibid pg. 115

[x] Ibid. pg 115.

[xi] Ibid. pg 41

[xii] Ibid pg 258

[xiii] Ibid. g.43

[xiv] Ibid, pg. 212.

[xv] Op Cit Clemente, pg. 82-83

[xvi] Op Cit Clemente, pg 64

[xvii] Ibid. pg. 207.

[xviii] Wehrmacht-Awards thread, Prussian Commissioning, 7/28/2004 Posted by Brian S.

http://www.wehrmacht-awards.com/forums/showthread.php?t=57874&page=2&highlight=commissioning

[xix] Op cit Clemente pg 43.

[xx] Ibid pg. 94

[xxi] Ibid. pg 101

[xxii] Ibid. pg 209.

[xxiii] Ibid. pg 72

[xxiv] Ibid pg 73-74.

[xxv] Ibid

[xxvi] Ibid, pg.150

[xxvii] Ibid, pg 150-157.

[xxviii] Ibid. pgs 158-159.

[xxix] Ibid. pg 160.

[xxx] Ibid. pg 210.

[xxxi] Martin, A.G., Mother Country Fatherland, Macmillan & CO, London , 1936 pg 16

[xxxii] Ibid. pg. 161-162.

[xxxiii] Ibid. pg 163-164.

NCO Helmets

NCO Helmets

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

M15 Steel Helmet Plates

M15 Steel Wappen

Joseph P. Robinson.

| In 1980 a collector named Lector Orrick started to put together a study on steel helmet plates. This was published in the Journal Kaiserzeit, and this article expands upon that. The question that we seek to answer is which helmets actually had M15 gray, steel counterparts. The requirement is to find an actual steel helmet plate that is magnetic, not a prewar brass paint over. The true test is to find a picture of each of these helmets. This is an enlisted phenomena for a helmet that was introduced in July of 1915. It was the last pickelhaube in use before steel helmets took over. There are several categories we will deal with: 1.) A documented example in a collection with a picture. 2.)An allegedly documented Wappen is from the Orrick articles. 3.)Undocumented examples. I am far from satisfied with the order and content of Wappen listed. However, I decided to stay with the Orrick listing as that way I could match up the documentation with his list. I know his methodology is not even alphabetical. Perhaps I will change it in the future.

Rather than list all of the different helmet plate types I tried to list only the sizes once. For instance, the 95 mm Prussian line eagle was used on several helmets. Rather than list them all I put down only the 95 mm Prussian line eagle. This includes no difference between gilt and silver Wappen. When it came to gray steel original color did not matter. I did this while trying to keep the original methodology. It did not always work and it doesn’t always make sense. Tony Schnurr has explained a great measuring technique that can standardize Wappen measurements in the following forum thread: http://pickelhaubes.com/forum/viewtopic.php?t=45 This entire article is based on pictures from other peoples collections. John O’Connor and Jim Turinetti graciously allowed me to use their line drawings from their excellent work “Imperial German Headgear”. You can purchase this work from the authors at: www.kaiserhelmets.com A review of the work is located at: http://www.pickelhauben.net/books/Turinetti.html The number of M15 helmets in my collection is zero. This is about research. Please send any corrections or additions I can use the advice. We can certainly use the pictures! |

||

| Infantry | ||

| Garde Eagle with Star |  |

|

| Semper Talis Ribbon Banner |  |

UNDOCUMENTED

|

| Grenadier Eagle — wide winged |

|

|

| Grenadier Eagle — 1655 |  |

UNDOCUMENTED

|

| 1626 ribbon banner |  |

UNDOCUMENTED

|

| FWR Eagle |  |

UNDOCUMENTED

|

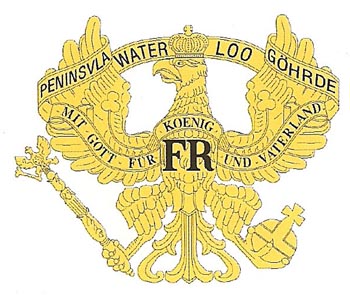

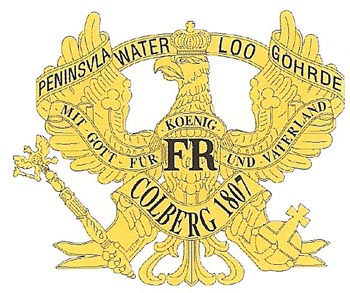

| Grenadier Eagle — 22 March 1797 |  |

UNDOCUMENTED

|

| Grenadier Eagle– Colberg 1807 |  |

UNDOCUMENTED

|

| line eagle with the initials FR

115 mm |

|

|

| line eagle — Peninsula Waterloo |  |

|

| line eagle — Waterloo |  |

|